Celebrity Twitter & its discontents

If celebrity Twitter is a graveyard, then fans are on patrol.

The Washington Post and Taylor Lorenz are concerned about celebrities on Twitter. Or rather, the dearth of A-listers using the platform in a pro-social way rather than as one of the many promotional tools at their disposal. The greener pastures they’ve expanded to—because they never really gave up Twitter, they just shifted their strategy—are framed as less toxic, thanks to the available tools and official oversight. Less general harassment, less fear of cancellation, and more ways to monetize content.

Plenty of us no-name users have terrible experiences online, trolls and pile-ons can come for any of us. But when we’re talking about celebrities — fan objects, human brands—it does everyone a disservice not to talk about who, in particular, is lashing out at them with a vengeance.

Fans are mentioned in the context of engagement, as if they are a passive audience and not a community with strong feelings of their own. That’s what happens when you target a community and stoke the embers of parasocial connection. Internet marketing veteran Tony Harris sat down and discussed Twitter strategy over five years ago. He presented the “FACE” system: Find fans, Aggregate fans, Convert fans and Engage fans. Engagement in this context is the same as activation, “a call-to-action. Once we’ve converted a follower, we want them to buy music, see a movie or otherwise engage with a specific piece of content.”

So when publicists talk about engaging fans, it’s not about strengthening the connection between artist and fan; it’s a one-sided hustle with an ulterior motive. This happens in all fandoms and all platforms, and most users who have direct communication with stan accounts— the hardcore fans— likely know that it’s a group that will very easily attack.

The harassment celebrities face isn’t primarily random. It’s targeted. We’ve seen fandom outrage in the Star Wars universe, leading to both Daisy Ridley and Kelly Marie Tran abandoning Instagram in 2018 as a result of misogynistic and racialized abuse.

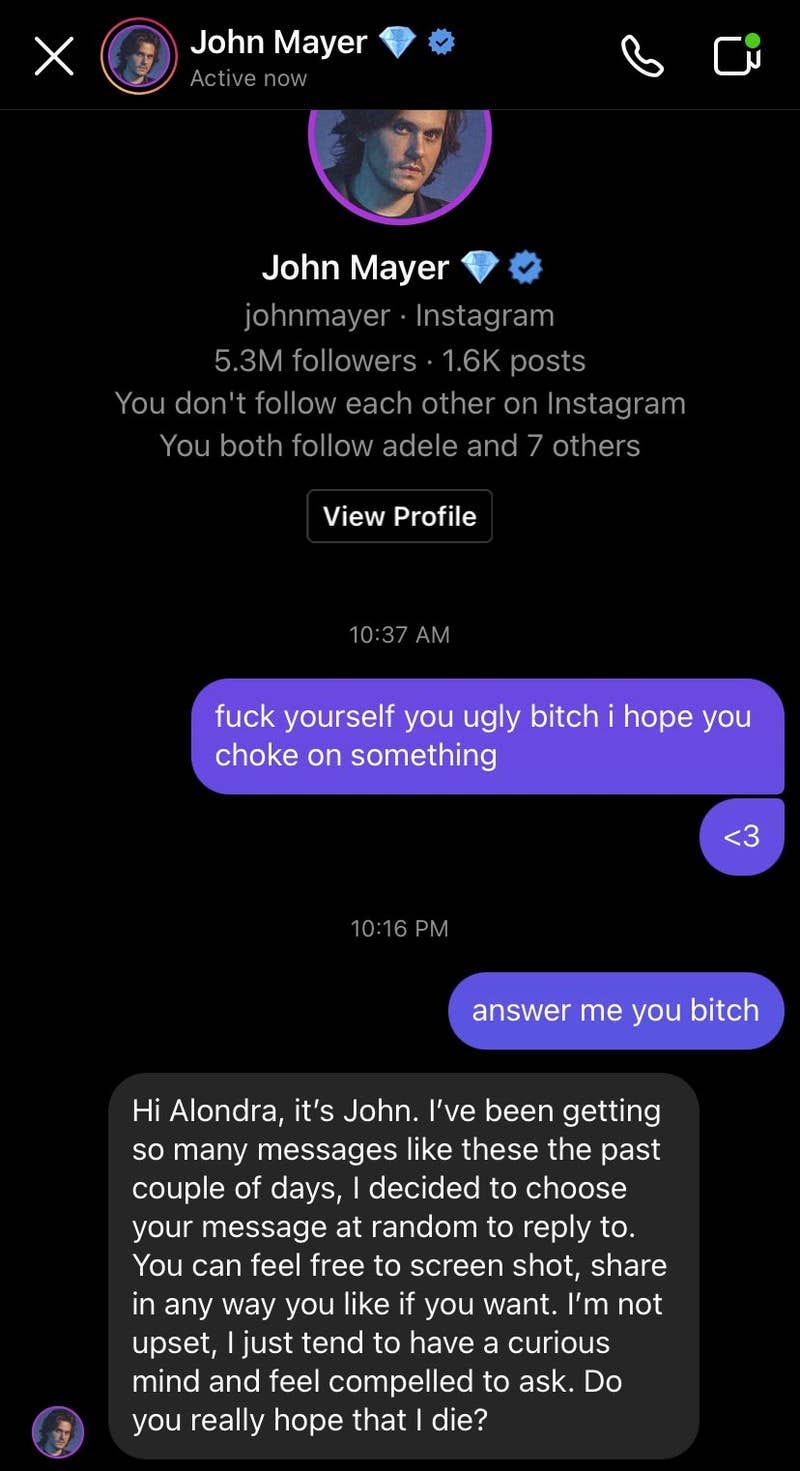

John Mayer, who is name-dropped in the article as one of the high profile people who doesn’t share like he used to on Twitter, recently made headlines when he confronted an angry Taylor Swift fan on Instagram.

The attacks— because there was more than one, more than this particular user— could be traced back to stan corners of Twitter and other sites. Whether Mayer’s response was a dictated or a recommended PR move or a genuine response, is impossible to know, but it worked. The user ended up apologizing, writing, “It was a dare. I’m sorry. I did not expect you to see.”

If we take her word that she didn’t think he would see it, why did she send it? If it was a dare, why did twelve hours pass between messages? Based on seeing this type of lashing out over and over in fandom, the cycle is recognizable. It’s possible she was aware or suspected that intermediaries would intercept, it’s possible she wanted to add to the glut of angry messages, so Mayer could really feel the rage directed at him. It’s also possible they were heat of the moment messages—brought on because fandom discussion vilified him and framed the fandom response as righteous anger. It’s a message of hyperbolic rage, but ultimately a mute threat that likely didn’t even feel good for more than a few seconds.

One Direction are often hailed as one of the first social media bands; the spotlight on the five of them and their families and friends and colleagues appeared at just the right time, when Twitter and Instagram were still fresh and exciting.

The online fandom was mobilized quickly, a strategy that paid off when their debut album debuted at #1 on the Billboard charts. Months of building and engaging with fans were enough to “activate” the monetary investment.

Out of the headlines, the band and their HQ spent over a decade stoking the devouring stans, and the risk of antagonizing fans— yours or someone else’s— increased with every year, the fandom climate souring and becoming a breeding ground for zealotry. What else can happen when the very aim of fandom management is to find and create customer and brand evangelists? The dark side of evangelism is what we’re seeing. The disappointment turned to rage; unwarranted, inappropriate, yet present, and impossible to ignore.

Twitter wasn’t the only place the band members and others were targeted; in 2017 Louis Tomlinson was targeted via WhatsApp, multiple numbers believed to be the same person were sending graphic violent threats, having also been the target of direct phone threats as well, law enforcement was brought in to assist.

On the flip side, occasionally the celebrities are seen as the instigators, as spurring on bad behavior and bullying from their fanbases when it benefits them. PopFront’s crusade against unsavory Taylor Swift fans is one that made many waves and headlines. With alt-right figures clinging to the conspiracy put forth by a Daily Stormer editor that Swift was “waiting for the time when Donald Trump makes it safe for her to come out and announce her Aryan agenda to the world.”

PopFront’s Meghan Hernig expanded on the conspiracy, fleshing it out and demanding that Swift speak out. She wrote, “Taylor’s silence is not innocent, it is calculated.” Swift’s camp didn’t play game and sent PopFront a cease and desist letter, asking for a redaction. The legal documents claim, “Indeed, through this story, you attempt to impose a duty upon Ms. Swift (and only Ms. Swift) to loudly state her views on whatever hot-button issue is circulating at any given time.” The ACLU took offense to Swift’s selective response and set off another trail of headlines. These were simply not acknowledged.

Part of the problem cited in Lorenz’s piece is that Twitter is becoming a work obligation rather than a social platform. It’s being delegated to the professionals, which is leading to the celebrity desert of Twittter today. But Twitter has been a professional obligation for celebrities long before the mid-2010s, and social media managers have been around since the very start. Adele claimed that her drunk tweeting lost her access to her Twitter account, “my management decided that [tweets] have to go through two people and then it has to be signed off by someone.”

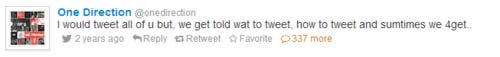

One Direction fans were given reason to question social media activity early on, in July of 2011 when the official band account tweeted out,

The rogue posts were written off and denied by Liam Payne on Twitter the following day, as well as Tomlinson on Twitcam, who claimed they were hacked and said, “so basically, it’s a load of rubbish”.

They shouldn’t have to delegate their social media presence to employees, but they do and they can. And fans know. They know that the person they @ might not actually be the one typing. Something that has also contributed to the dehumanization of the people behind the accounts.

When Wikileaks released emails and documents from the 2014 Sony Pictures hack, 1D fans who had remained suspicious about the authenticity of Twitter activities of the band were given more ammunition.

The reveal consisted of an email chain complaining that Tomlinson’s official account had tweeted excitedly about Captain America 2, a rival studio’s properties. Amy Pascal’s email reads, “having one of the one direction band(louis no less) helping the Competition is a little alarming.”

The “positive fan engagement” that we’re told we’re missing out on has most likely already been mediated and filtered through the industry. It’s one thing to know that a platform is used for promotional purposes, also, but another to be made aware that there’s no real way to know if any written communication was ever authentic. With the knowledge that tweets may be dictated or even typed by someone else, suspicion becomes part of the base fandom is built on.

The red thread here is stans and fandom. Seeking the most intense, most zealous, most dedicated fans can backfire in this most surprising of ways.

Lorenz isn’t wrong that the landscape and texture of Twitter has changed; normally the up and comers would be replacing the talent that has graduated from wrangling followers. But the up-and-comers don’t easily overcome the existing hurdles. It’s one thing to have to fight against Big Industry (of your choosing) and have to navigate around gatekeepers. It’s another thing when fans—sometimes yours, sometimes others’—act aggressively and create unnecessary friction. It hurts the fandom communities themselves, as no one is safe, but it also hurts all the peripherals.

The scrutiny and laser-focused attention of stans is not something you can prepare for, especially if it’s not even your industry. We’ve seen and heard of music reviewers and entertainment journalists being targeted by zealous stans. It’s the same energy converted into offense mode.

A recent example is that of Juwon Park, who caught the ire of BTS fandom this week. A featured performer on one of the upcoming album tracks has a history of sexual abuse allegations and she made the mistake of talking about it.

The stans were active on Twitter, compiling threads of counterclaims, replying and quote tweeting and DMing, but they weren’t constrained by the site. Some flocked to Park’s LinkedIn account and started filing complaints with her professional connections.

A 2018 Guardian article deconstructed the phenomenon well but zeroed in on the subculture of gay stans specifically. One of the attacks cited is another one where a newer artist is being punished for stepping out of invisible bounds. In this case, being up against four performers also meant four times the abuse.

It is hard to overestimate how meaningful the fan-diva relationship is for gay men. What is so perplexing is why this pseudo-religious devotion has always been laced with spite. Earlier this year, pop singer Hayley Kiyoko criticised Rita Ora, Cardi B, Bebe Rexha, and Charli XCX for their single Girls, a song about bisexuality that she, as a lesbian, thought was appropriative. Within hours, stan Twitter had unearthed and circulated incriminating tweets by Kiyoko from nine years ago (when she was 18) in an attempt to “cancel” her – excluding a person entirely from online discourse, except as the target of hate memes – for daring to critique a song they liked.

The article consults with Dr. Lynn Zubernis, professor and fandom expert, who emphasizes that the aggression in fandom was in no way unique to gay stans but instead a result of the intense emotional attachment fans will form with their fan objects and can be seen in fandoms outside entertainment. This perpetually unreciprocated emotionally outpouring can curdle quickly if expectations fall short, she says, “That is the dynamic behind the ‘mood swings’ you see in fandom, where fans love something one day and turn on it the next. It’s not about misogyny. It cuts across gender, sexuality, type of fandom, even time.”

An incident involving Welsh singer-songwriter Marina Diamandis is also mentioned in the Guardian piece, and I remember seeing the exchange on Twitter as it took place. She had deleted her Instagram account at the time and confronted an account that was being rude, elaborating on the effect stans were having on her.

Diamandis points to the fan culture specifically as a repellant to using the site. Around this time she also changed her stage name from “Marina and the Diamonds” to simply Marina. She cited her desire to be treated as a human rather than as a persona. Whether this decision was influenced by the toxic fan culture is impossible to say from the outside. But her point may have been more impactful because of the frank online exchange, reminding her fans that her account is run by a real person. Because that’s true regardless of whether it’s actually the performer tweeting or not.

Her response to a since-deleted tweet (hence the screenshot) nails the problem by defining it as a culture of degradation. It’s present among fans, in fandoms, usually perpetrated by the stans—the hardcore devotees. But even if we don’t spend time on stan Twitter, we’ve seen the effects of this culture and might even have participated, gotten swept up in the river of rage that is so easily dipped into.

It’s a bigger problem than fandom. But fandom can’t be excluded from the landscape of celebrity Twitter, not when it’s the primary driver behind so much artist and celebrity harassment.

It's odd to me that anyone whose used social media and experienced harassment knows at a small scale it can be horrible and feel hard to manage. I don't know why we'd think it's possible to address that concern with people who are reaching potentially millions of people with their content. (Lorenz, who've talked to before and think is chill, is basically asking for mods.) It's like saying I need to be concerned about the mental health of the Pepsi brand, since people make fun of it on Twitter. I'm not saying people should be awful to famous people and that folks shouldn't take responsibility. But just that it's hard to conceive of having a platform being a two way street with that much traffic.