Fanatic (2021) and the reality of fan disillusionment

When fan objects commit moral violations, what happens to the stans?

It takes a lot for me to be interested in films and shows about fans. This is because I’ve noticed most of it alternates between puff pieces and ghoulish take-downs, with a required dose of hagiography for the fan objects in question.

However, Fanatic (성덕), Oh Se-yeon’s 2021 documentary, seemed different from the get-go: it’s about the fans left behind when their fan objects have had a (deserved) fall from grace.

This is a deeply personal documentary on Oh’s part. She participates on-screen and discloses her struggle with the dissonance that comes with being confronted with an uncomfortable truth. In her case, she spent 7 years as a fan of singer Jung Joon-young, who was convicted of aggravated rape in 2019. Evidence of these crimes were uncovered in relation to the Burning Sun scandal that rocked South Korea.

Mr. Jung, along with other members of an online chat group, had bragged about drugging and raping women and had shared surreptitiously recorded videos of assaults.

This wasn’t the first time Jung was in hot water, having been the subject of allegations in 2016, which fans defended him from. But the evidence made the allegations a reality. What’s a fan to do when the illusion of their idol’s good nature is shattered so definitively? This isn’t about dating the wrong person, having a drug scandal, speaking out of turn, or delivering a subpar product, these actions are recognized as criminal for a reason.

The documentary doesn’t try to make fun of or pathologize fans; Oh wants to understand the emotional response that she and her fellow fans experienced. In an interview with Korea JoongAng Daily, she explains,

“When you become a fanatic, when you love someone to that extent, you don’t realize that you're doing that, that you’re the giving tree. I wanted to give everything to him, but I didn’t feel like I was sacrificing or giving up too much. That’s how immersed, devoted I was.”

Oh’s comment that “you don’t realize that you’re doing that” stands out as part of the problem. You don’t realize how deep you’re in until something happens that challenges your reality. It’s why I find it difficult to address comments about how stans are happy to be shelling out thousands and dedicating their lives to their fan object. Many things that we engage in willingly and that feel good in the moment are not necessarily good for us. Euphoric highs and dopamine hits don’t translate to healthy dynamics, in fact, they usually come at a cost.

Worse yet, we may be in denial about what we’re doing to ourselves, and the ultimate cost it may have. Oh revisits her journals in the film, including the clear-eyed question she posed in one, “What if I regret this when I go back to being a normal person who doesn't want to see you anymore?”

In a way, the film explores whether it’s possible to go back to being normal after this type of crisis. It’s one thing to grow out of your interest, have it displaced by real life activities and attachments, it’s another matter entirely to be faced with a conflict so profound that it shakes you to the core.

Oh speaks to friends of hers who have experienced similar fractures with other artists. Even her mother is featured as someone whose favourite actor was disgraced in a #MeToo scandal. Her quest to understand the driving force behind supporters that remain loyal lead her to a political rally in support of former South Korean president, Park Geun-hye, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison in 2018.

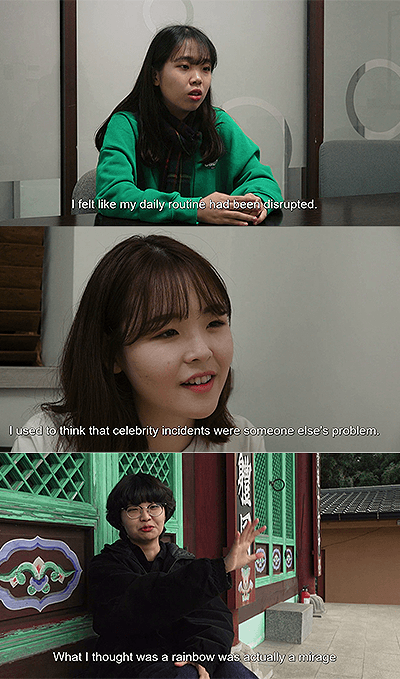

The discussions with fellow fans who were trying to make sense of their emotional reactions really resonated with me. The so-called “waking up” to just how deeply invested they were in what turned out to be an illusion. Because when there’s a perceived moral duty to defend your fan object, you’re operating on deeply felt knowledge that it’s what’s right. But that type of knowledge and belief can mislead us. Where do we go when the veracity of this knowledge, the basis for this unshakeable faith, is completely destroyed?

The evergreen response to fans feeling betrayed is that their fan objects don’t owe them anything. But this isn’t about the fans being owed something, it’s about emotional responses that cannot be reasoned away.

“Are we victims or perpetrators?”

There is also the question of what fans’ role is in all of this. Many fans feel a degree of responsibility for what happened, even as they themselves feel victimized. If you find it ridiculous that fans feel betrayed by someone they don’t know, the fact that so many of them feel that they need to answer for the crimes of their fan object should reveal the degree of attachment we’re discussing.

So much of it is about feelings. We can know, logically, that we aren’t responsible for someone else’s actions, but the guilt can still gnaw at you with tremendous force. Would these fan objects have become criminals even without being in the public eye? One fan feels like she helped commit the crimes. Another wonders if the adulation fundamentally changed who the idol was for the worse. Oh says in the film, “It seems like the support and love I gave that person became the driving force behind the crime and deception.”

There are ways stans express devotion that are actively, objectively harmful. One of these is the harassment journalists might face when going against fandom narrative. If a journalist goes even further and alleges actual crimes, all bets are off.

Park Hyo-sil was the first to report on the allegations against Jung. Her piece was published in 2016, years before evidence was made public and charges were filed. She was immediately targeted by defensive throngs of fans. She told the BBC in 2024 that her employer was threatened directly, “If you don’t sack her, we’re going to set fire to your building.” She was pregnant at the time and partly blames her miscarriage on the stress the escalating harassment caused.

Park is featured in the documentary in one of the most moving scenes, wherein Oh apologizes for her role in the backlash that Park faced. She’s clear that she can’t speak on behalf of the fandom at large, but that she wants to take accountability for her behaviour. Park is surprisingly receptive, going so far as to say she understood the fan reaction, all things considered.

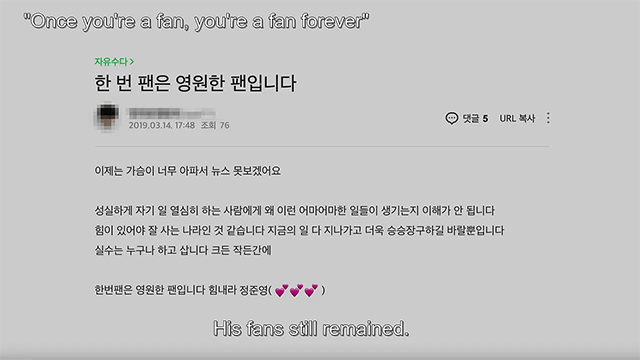

But some fans still remain. Excuses are made, even in a case like Jung’s. He was an innocent bystander and was tricked, or took the fall for a friend that was the primary perpetrator. It may seem extreme, but the mechanism behind these copes is the same across the board. Whether you want to call it betrayal blindness, cognitive dissonance resolution, or plain old denial, it’s operates the same whether a fan object is being defended from accusations of greed or an outright crime.

The moral violations may be trivial, but the response to them can nonetheless be outsized. Whether it’s right or justified is irrelevant in the face of the emotional tsunamis that materialize.

These experiences are universal, and a result of our parasocial investments. Seemingly an obvious statement, yet I feel like it’s rarely acknowledged. Or rather, parasocial attachment is treated like something that only happens to weirdos, but it’s something we all engage in. The most extreme form is something I’ve come to call parasocial limerence, which denotes a more intense, obsessive form. This term may be needed to differentiate between degrees and types of parasocial attachments.

If we can understand the process and the psychology behind these mechanisms, perhaps we can be more forgiving of ourselves when we realize that we inadvertently dove into the deep end, and find ourselves responding in these uncomfortable ways.

This is only tenuously related to the post, but I feel it's worth sharing with you.

A few months ago I had to teach Foucault's "Panopticism" to a college freshman class. One of the questions I presented them with ran something like: okay, so we've established that surveillance is a means of control: when somebody knows they're being monitored, they tend to behave how their audience wants or expects them to behave. So how does someone like Taylor Swift fit into this schema? We can agree that she's one of the intensely surveilled people on the planet; she can't do anything in public without her fans knowing about it, and there's occasionally intense speculation about what she does or thinks in private. So according to Foucault, what's the actual power dynamic between Swift and her followers?

It didn't click. The students had been following along up to that point and comprehended the basic idea of how watching exerts a form of control over the watched, but the whole thing broke down when they were asked to apply the same logic to a pop star. It was fascinating to see.

One thing I've also noticed re: fan denial is when news articles/fan discourse exaggerates or blows the alleged crime way out of proportion that it gives the fans of the alleged criminal "proof" that everything is fake. I have a lot of examples from K-Pop about this.

To give an easy one--there's a photo of an idol wearing a Nazi cap and there's a swastika that does appear to have been photoshopped on the cap. His fans seeing that the swastika appears photoshopped then say the entire picture is photoshopped, completely overlooking the SS skull logo on the cap that is not.

Anti-fans say it's proof he's a nazi; stans say the whole thing is photoshopped.

This desire to have everything black and white has to play into the parasocial stew at play. We can't just roll our eyes at an idol playing edgelord, for fans it's proof he has to be either evil or an innocent framed angel.