Fandom missiles, ready for blast off

The fan pyramid model is outdated; the market isn't static, and our representations shouldn't be either.

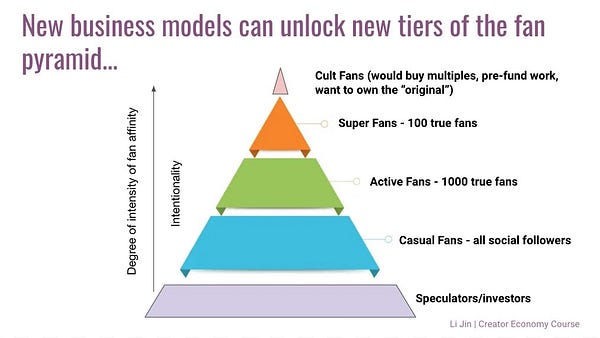

Pyramids have been analogous with fan/dom illustrations for quite some time, they are nearly ubiquitous in marketing and business contexts. They’ve always lacked something in my eyes, but I didn’t figure out what it was until someone directed me to Li Jin’s updated version:

This new pyramid has added two layers to the standard one: a cult fan cap, sharp and precise, and a broad foundation that represents investors/speculators rather than fans themselves.

I very much agree that cult fans as Jin refers to them are an essential part of current fandoms — I call them stans—but it’s really the investor layer that clicked with me. Usually, these pyramids are used within the industry: in marketing books, in PowerPoint presentations, and in meetings. They are used to dissecting fan bases, not to observe them, so they aren’t part of the image. Adding them as a foundational element rectifies the myth of fandom-driven properties, as well as the “overnight sensation,” there is a scaffolding in place propping up the brands we’re so used to seeing, even if we don’t think about it.

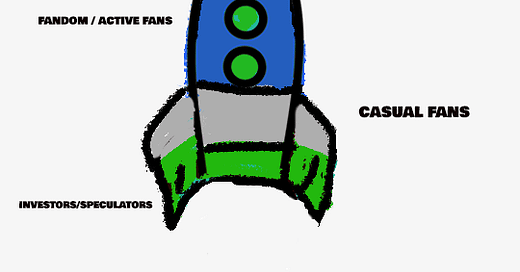

The pyramid itself isn’t the best illustration of fandom landscapes; it’s too static for the climate of today. I think something like a rocket or missile is more apropos, or even a pesticide plane, its reach depends on how big the fan base is, where it intersects with other fan bases, and how the people behind it all behave since they are the ones loading up the fuel.

Now, this is a very basic, basic version of what a fandom that has been tended to might look like as part of a bigger picture. But that is a rare situation in our entertainment climate. It’s easy to notice how publicity cycles work when you pay attention, but it’s rare to contextualize what we’re seeing (and what we’re not seeing since we don’t see it) as part of a bigger picture.

I also intentionally left the little windows as industry hubs that continue to deal directly with fans rather than media, because that has been part of the equation since the very beginning of fandom. This is where what I discussed in my astroturfing piece fits in: the microtargeted advertising and campaigning being performed with the help of fans and stans.

That rocket illustration, however, remains a pipe dream for many performers, brands, corporations—what have you. It’s just one shape it can take. So of course, I had to create some variations.

A “fan driven brand” can be likened to a new band just getting its bearings in a local scene. They amass fans and an audience, and maybe they have a manager or a booker, or some fellow musicians that help propel them forward.

When we talk about the “1,000 true fans” model, we’re talking about a fan-driven brand. There’s still some backing, and certainly, it can keep going and growing, but it will never get as far as a rocket with a super-charged motor. This is where the dream of a record deal comes in because the fans alone do not have the capability to book and promote tours, service songs to stations and playlists, organize showola exchanges and so on.

The industry-driven brand can be a project that is launched by the industry rather than picked up, think of the Disney stars ushered into the limelight who would end up amassing loyal fan bases and stans, but had none at first.

It is also what a brand fandom might look like when the hardcore fans have become alienated and abandoned ship. Case in point: Bruce Springsteen.

When Springsteen’s run of #1 albums was threatened in the UK by Louis Tomlinson’s sophomore effort, there were no punches pulled in pumping up the promo. BBC declared his album that of the week, and he made an appearance, he also headed to some talk shows last minute to reach some of his casual fans that weren’t aware of his new release.

In this case, the bulk-buying fans won out, but this was just one battle in an overall war. It’s an empty victory that does little to establish a brand or expand its visibility.

Backstreets Magazine, the fan-run resource that reported on the chart battle, has since declared its shuttering. This seems to have been a reaction to his approach to ticket pricing, making the disconnect between what he represents to those hardcore fans and what he shows all too difficult to reconcile.

So he has a mostly industry-driven rocket, now, like the second rocket. But he also has massive amounts of casual fans, and the fandom itself is likely just fine. It’s unlikely that Backstreets Magazine will be replaced anytime soon, it was 40 years in the making—but there may very well be new cult fans that develop from the fandom. He has time, and enough of a head start that he’s still leading the race.

The importance of the industry boost is especially noticeable when you see how outsiders’ success is framed. A surprise Academy Award nomination for Andrea Riseborough’s performance in an independent feature, with no studio campaign, has been called cheating. Discussions about charts will often blame fans for “gaming” them— as if the process of gaming charts isn’t the entire purpose of many PR departments.

The third and final illustrated rocket is the hydra. It is a stage that happens to many brands. Whether it’s a band being split into individual fandoms or ship fandoms, or a franchise tunneling through the atmosphere and growing vertically thanks to the expansion of properties and accumulation of fans. It’s also where you’re most likely to find established anti-fandoms.

I haven’t thought of a way to illustrate the actions of anti-fandom in the rockets, but ultimately, its growth is part of what makes these online spheres so toxic. It’s a reaction to our own powerlessness, hyper-charged, and that’s all the more notable in the hydra than elsewhere.

A much more in-depth analysis of the fandom influence myth is forthcoming, so stay tuned for that. It will explore what happens when a hydra rocket splinters entirely, and the discrepancies in fandom impact become inescapable.

It’s easy to picture anti-fans as outsiders, but most of the diehard antis come from inside the fandom. Fans are told they hold the cards, but they were handed the deck by insiders. Anti-fans cannot really fight the monolithic powers that be, all they can do is try to destroy from the inside, and project their own anger onto others. Once they realize they’ve been had, it’s too late.

We can learn about what creates these anti-fandom backlashes, and we can identify and contextualize their behaviour, but for now, it will keep growing. There is no upside to those in charge addressing what they created, especially not as long as they remain shielded from repercussions and can keep the fuel coming.

For now, the internal fandom conflicts seem isolated to the fandom and cult spheres but also spilling over onto outsiders in an effort to be heard, and to make a change.

It’s a “confusion of hierarchies” as Sam Adler-Bell called it, when writing on the cinematic eat-the-rich films that bookended the year, “The have-nots can only hope to drag the haves into hell — where we already reside. With cruelty and hopelessness for all.”

Great work as always!