I haven't thought of the Norwegian TV show SKAM in years, but a visit to Oslo has brought it top of mind. It attracted much fandom attention in my Tumblr circles, but the fandom was far wider reaching than just that site and Western fans, gaining popularity in Russia and China on their platforms as well.

SKAM was produced by Norway's public broadcaster NRK, and its purpose was to explore topics close to teens’ lives, in particular, teen girls. The show was more than just a show; using transmedia storytelling and what has been called “shared temporality” as a way to propel the narrative and connect with the audience.

This unconventional method of storytelling and relating to the audience has been discussed widely, but while it's necessary to understand it's not my focus at this time. Jill Walker Rettberg summarized it the best in her 2021 article;

“A key feature of SKAM is that it was published online first, in daily or more frequent posts to SKAM’s website. The content of these posts varied between short video clips, screenshots of text message chats between characters, and Instagram posts from the lead character. In addition, fictional characters from the show shared Instagram and YouTube posts that were not published to the official website but that were picked up and shared by fan groups on Facebook and elsewhere. Video clips from each week were compiled into traditional television episodes of 20–40 minutes that were broadcast on Friday nights.”

—“Nobody Is Ever Alone”: The Use of Social Media Narrative to Include the Viewer in SKAM

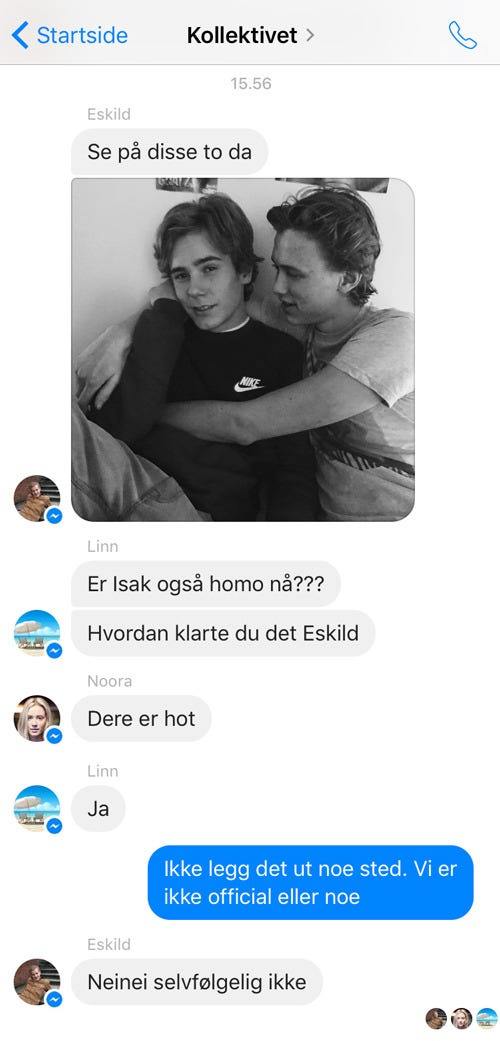

I became aware of the show during its third season when the plotline revolved around a potential gay relationship between the season 3 lead Isak, and the interloper, Even. As the show was explicitly targeting Norwegian teens there was no official translations or subtitles available, but fans were quick to provide translations and set up ways for international fans to watch the clips with subtitles.

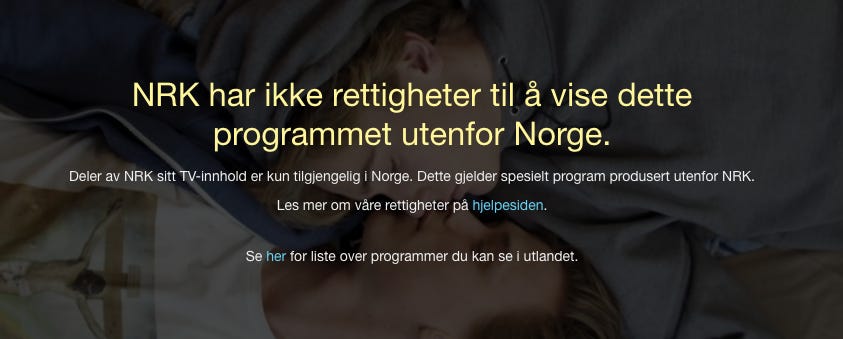

These valiant efforts were appreciated by most, but there remained a loud contingent of the audience who didn't understand why there was no official subtitles and immediate translations available on the official site. With such a large international audience it would surely make sense to expand their reach, they would ask obtusely. That the show had already been pitched to foreign markets and rejected due to its racy content seemed irrelevant: the audience was there now and NRK should've capitalized on it when they could.

When the official NRK site geoblocked all the SKAM content it was seen as an attack on international fans. The actual reason was that NRK had been informed they were in breach of their music licensing agreements. To anyone who has had to deal with labels and sync paperwork this makes perfect sense. To fans it was an inexplicable attack and hostile statement.

Of course, geoblocking is simply a hurdle in fandom and it was worked around by enough people that the content was made available just a little later than normal. The fan entitlement was palpable in that it shifted to those who were procuring, translating and distributing content.

There was also the lack of boundaries that has become synonymous with a successful fan object that seeped into the Norwegian scene, something no one was properly prepared for. While I mostly encountered English speaking fans online who expressed a desire for more access, this was a universal issue.

The school used as a filming location was in use throughout the semester and experienced an influx of curious overseas fans. Danish fans in particular were called out by the principal of the school as using the school grounds as a safari of sorts, lurking outside classrooms and by the characters’ lockers.

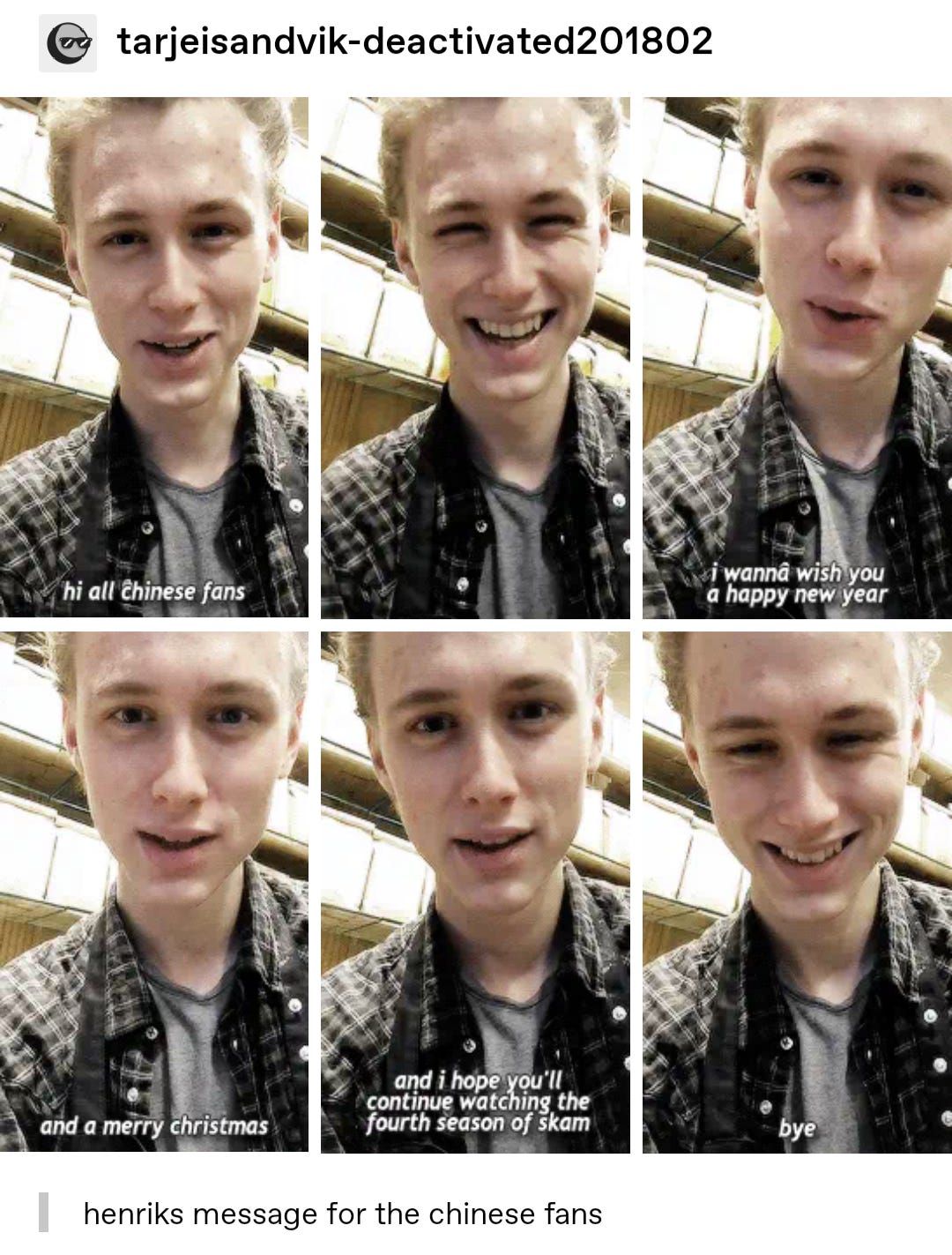

“Skam was aired on TV when I attended Nissen, and there were at times huge groups of Asian tourists in the schoolyard during breaks. The principal finally had to let them know that they weren’t allowed inside the school. And there are many foreign fans attending my theatre performances who are there just to film and take photos of me without understanding anything of what’s being said on stage. It’s rather weird and a bit uncomfortable.”

— Tarjei Sandvik Moe, quoted in ELLE magazine, translation by fans

Henrik Holm who portrayed Even was the target of much covert photography and fan approaches at his place of work; enough so that fans would decry his privacy being invaded online with regular intervals.

The fans believed—hoped— that the Isak/Even storyline would continue in season 4 even though the purpose of the show was always to focus on a different character each season. Many thought that since they brought the international fans' interest to the country and the show, they should be catered to. But that was never the plan; yet another example of how fans have been told they have more impact than they do.

The global interest resulted in the format of the show being sold to many markets, but this wasn't what they wanted. In fact, most fans were dreading the many adaptations that were announced.

"I am worried about recomposing quality of the Chinese version. Some Chinese scriptwriters do not have ability to make sense of a story," a Chinese fan of SKAM said, once again highlighting the disconnect between what fandom wants and what industry wants. Regardless of the new or adjusted aims of local productions it would never have been good enough for the fans. They wanted more SKAM; not new versions.

Still, as the show continued with its final season the global fandom received the occasional nod throughout. And at the very end the audience was addressed and included into the narrative by weaving in their social media responses.

I've yet to see another media property use the shared temporarility that was so effectively used in this case, but it may be for the best. The entire purpose was to blend fiction and reality, something that we already seem to struggle with when it comes to online content. As it is, much of celebrity content and activity is read as a narrative to follow and adjust according to fan desires.

I wouldn't be surprised if we get some sort of Marvel sanctioned social media app where their characters “live on” off screen as a way to keep the fandom satiated. It might help keep the engagement high and the complaints isolated, or at the very least, limited to a particular platform.

My concern, which may be paranoid, I admit, is that the more fans realize their “empowerment” has been illusionary the more lashing out there will be. But that remains to be seen.

Until next time.

I think we must be connected somehow because earlier today at the gym I was thinking to myself about how to approach different aspects the illusionary empowerment of fans in my Master's Thesis. I was not aware of this case and I'm definitely gonna take a closer look! Lastly I want to say that, I often feel that decisions that explicitly refuse to go towards what fans seem to be requesting are probably based on a perception (data-driven or not) that there will be a demand anyway. I'm a friend of Kara from The Idol Cast and I'd love to talk a bit about my research when you have the time ^^

I came up against this "standom" last year myself in Oslo. Against my better judgement I paid 150 dollars for a Bob Dylan concert in Oslo to sit on an uncomfortable plastic chair for 2,5 hours. "See the legend while you can" they said. A red spotlight shone direct into the eyes of the first 40 rows, security patrolled the aisles to make sure that nobody spoke or laughed, and bathroom breaks were only permitted in the pause between songs. I don't know what the hell it was I attended, but it wasn't rock and roll and there was not a single recognisable song.

The strangest of all? Everyone I spoke to who went loved it. I had a migraine for days and wondered for long after what am I not getting? Was the concert a collective validation of an identity curated by Dylan or was it spectular and I just don't have any taste?