Swarm is a nightmarish fairy tale for outsiders

Fandom is merely ancillary in Amazon Prime's horror series Swarm.

Following the release of Beyoncé’s Lemonade in 2016, a satirical news site published a story about Marissa Jackson, a Bey stan who allegedly committed suicide because of the narrative of the album.

Swarm breathes life into Jackson (Chloe Bailey) and adds to the mythos of toxic fandom by adding the character of Andrea “Dre” Greene (Dominique Fishback), an avenging adoptive sister with a thirst for blood. The young women shared a love for Ni’Jah, the Beyoncé stand-in with 26 Grammys, a cheating husband, and twins on the way.

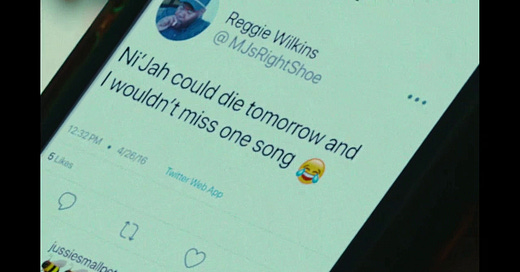

After the loss of her sister, Dre takes targets Ni’Jah naysayers one by one, giving them a chance to repent by asking who their favourite artist is, but not revealing that their answer will determine their fate.

We’re told from the get-go that the story is true, or rather “not fictional,” from the opening episode slates but also from co-creator Janine Nabers. She told ET, “This story is 100 percent taken from real events and real internet rumours and real other things.”

The key sentence here is “real internet rumors” — and Swarm works as an extension of these online urban legends. It uses “real events that have existed in the world” but has also been “legally combed through” because it couldn’t be on Amazon otherwise.

Jackson’s suicide may have been a hoax, but that doesn’t mean such extreme actions haven’t taken place in fandom. Following a publicized attempted suicide in the One Direction fandom in 2012, journalist Aja Romano addressed the topic. She gave credit to the users that stepped in with help and contacted authorities but also pointed to the double bind presented: the happy ending of the fan’s rescue also came with a big boost in followers.

One person was saved, but Romano pointed out that, “the reaction from the Twitter community borders on glamorization of suicide as a means of garnering attention that some fans feel they can’t get any other way.” In the years since, it’s only become more difficult to parse what’s true and what isn’t, and the coyness of Swarm’s creators isn’t helping.

The unfolding of Dre’s story comes off more as a canon-divergent alternate universe fan fiction; a revenge fantasy told by disgruntled fans, rather than a look at toxic fandom. The fans, the fandom itself, are barely present as Dre’s psychosis unfolds, which adds to the illusion that this is all a retelling targeting a captive audience.

Dre is a protagonist in the truest sense: fuelled only by her own desires, unaffected by the online swarm of killer bees that she supposedly is part of. They remain in the dark as she scrolls through their grasping theorizing, not seeking the recognition and praise she could amass.

So maybe we’re watching the embodiment of online rumour mills: the pacing, the unrepentant violence, and her simplified motivations have the same flavour as message board threads or TikTok conspiracies. It’s cobbled together from online breadcrumbs and questionable sources, all for effect.

We know that fans—stans— have few qualms when it comes to sharing information and crossing boundaries, and it’s hard to believe no online observers would raise suspicions about Dre’s behaviour.

The police lagging behind? That’s believable. But there’s no way the swarm of killer bees wouldn’t notice Dre’s erratic posting and put two and two together. Stalker fans are no joke, and while their speculation is rarely picked up by authorities, there are no barriers to information online. She would have been under their microscope in no time, and that duality of fandom being aware of something while authorities flounder would have made for a thicker plot.

It’s also difficult to look at the series as a representation of fandom when fandom itself is absent from the equation. Yes, Dre runs an update account, but she doesn’t interact with anyone online. Her fandom friend is her sister, and despite being told repeatedly that her online friends aren’t real friends, there is no indication that she even has any online or fandom friends.

Yet, the series does get some things right. When Dre encounters a commune (cult) led by Eva (Billie Eilish), she follows their advice and participates in their rituals. They don’t reject her love of Ni’Jah, but treat it as an entry point into her psyche.

When Dre is asked to reject this primary belief attachment, however, Ni’Jah wins out. The commune was an acceptable tool to get closer to Ni’Jah, but she had no interest in replacing that belief attachment. In one way, her fandom saves her in this situation.

There’s also the lack of sexual motivation, which is a pleasant surprise. So much discussion around stans is framed around insatiable desires, but Dre doesn’t want to sleep with Ni’Jah, she simply wants to be absolved, blessed, and baptized by her Goddess.

Stans are rarely this straightforward with their fan object attachment, the real world full of more contradictions than any green lit project, but it still rings true. She even manages to attempt a romantic relationship, hoping to for someone new to worship Ni’Jah with.

And the end we get suggests Dre gets what she wants. She is held, however briefly, basking in the acceptance of her saviour.

The series isn’t bad by any means, it’s the fandom aspect that is lacking. It’s nothing but a conceit to tell a story about a young woman on a killing spree. Dre’s fandom is a footnote, an easy excuse for her aggression, but it’s really the loss of her sister that brings on her psychosis.

The Philippine film Fan Girl does a great job of portraying the stan perspective and the shattering of the protagonist’s rose-coloured glasses.

Ultimately, it’s an easy watch with good acting and music, but to absorb the message of reality or authenticity would be a mistake. We all know better than to take corporate press releases as fact, the same goes for approved non-fiction fiction.