The Road to Fandom

Fan worship isn’t always what it seems. Especially not when businesses get involved.

Originally published on Default Friend’s subscriber-only feed on October 5th, and edited by her. Formatting and photos remain the same.

Just five years ago Troika, which bills itself as a “brand experience company,” set out to do a yearlong in-depth study of fandom. As one might expect, one of the aims was to use the results to help industry be more “fan friendly,” but not only that; brands should anticipate and understand the depth of fan attachment and utilize it to improve ROI. The completed report tells us, “Fans are the most avid of all consumers – investing more time, spending more money, and sharing more of what they love. Fans can be a brand’s greatest asset and the most genuine form of advertising there is.”

Troika isn’t the only one telling businesses (and one might wonder, who else? Politicians?) that fans should be accounted for and targeted. Multiple business books advocating the same have been published over the past few years. Some of these titles include: Fanocracy: Turning Fans Into Customers and Customers Into Fans, Monster Loyalty: How Lady Gaga Turns Followers Into Fanatics, and, perhaps more ambiguously, Creating Customer Evangelists. The road here was slow and then sudden.

One day, writing real person fiction was an “ethical violation,” even within fan communities, the next, a self-insert real person fanfic is franchised and turned into a blockbuster film. Fandom went from existing almost exclusively in private spheres, to being broadcast online, inadvertently making fandom management much easier for industry.

Some might entirely blame the fracturing of fandom on the trappings of social media, and it’s a factor, but it ignores those with a bird’s eye view of the playing field. Fan management isn’t a new—another way to look at it is just “audience development.” But the precise and granular way it’s being done today has some unexpected side effects.

The Early Days of Fandom: Rudolph Valentino’s Funeral

One could say that fan management became a worthwhile investment back in the early days of Hollywood.

Though the studio system produced demanding divas (which were, as you might expect, often difficult people to work with), demanding divas produced growing fan bases. And fan bases created fan mail, which started to arrive in droves. Fan mail had never been dealt with on such a scale, demanding new departments to be formed to sort through it all. These letters provided essential feedback to the studios: they knew exactly who the public wanted to see more and less of. Consider these a piece of early analytics.

Fans also helped cement that movie stars were quasi-aristocratic figures to the public. In these early days, Hollywood execs still wondered whether celebrity culture was worth the investment. When Rudolph Valentino suddenly passed away after an illness, this was put to the test.

When Valentino passed, he’d been in the middle of a national publicity tour, and worse yet, he was in debt. A lot of it. At the time, there was no precedent for celebrity worship that could be sustained after death. No sorrowful tweets; no mountains of Beanie babies and flowers left at celebrity graves—Valentino’s death presented the very real possibility that his final film might all be for naught. But he had an X factor, something that was still new at the time: a giant fan base.

So for one of the very first times, Hollywood decided it would leverage it. The first step was for the funeral to be spectacle. Publicist Harry Klemfuss was put to work and pulled off an outrageous stunt involving actors posing as fascist guards sent by Mussolini. (The illusion only lasted until Rome denied involvement.) Meanwhile, tens of thousands of people filled the streets of New York and the mass of people outside the funeral home became a mob. Police got involved and were told people had come because the papers informed them that, “Valentino wished his body to be viewed by his fans.”

Did fans really save Star Trek from cancellation?

While the celebrity industry remained sustainable long past the studio era, television’s entrance into people’s lives allowed for a new type of fandom to form in new spaces. With decentralized fans, one might not anticipate an active fan community, but Star Trek proved otherwise.

Star Trek is cited as the first show that received sustained fan support at the prospect of cancellation. Hailed as a grassroots effort that empowered fans across the country, the question is: how grassroots was it really?

Star Trek’s creator, Gene Roddenberry, was concerned about cancellation in the first season. It was this concern that spurred his friend, science fiction author Harlan Ellison, to start a small, selective letter campaign. Ellison wrote his fellow intellectuals and urged them to contact the network. NBC had to be told that the show was appreciated by educated adult audiences such as themselves, not just what the new and faulty ratings systems indicated (which was not much).

The “Save Star Trek” campaign was launched in 1968. Bjo and John Trimble, friends of Rodenberry and fans of the show, got involved when they got wind that cancellation was nigh, again. They were given access to a treasure trove of fan letters and every return address was used to tell them about the campaign.

NBC eventually announced Star Trek’s renewal on-air, pleading for the letters to stop coming.

The campaign had been a roaring success, and while fans deserved a lot of the credit, a mythology was quickly built that obfuscated who was behind it. Bjo, who long received sole credit for saving the show, has since explained that while she was the public face of the campaign, John contributed equally from the start. The burgeoning women’s movement meant Bjo was a better representative, and that was all. Roddenberry himself also contributed to the impression that he was steering behind the scenes. His welcome letter to official fan club members suggested they may, “twist the peacock’s tail,” a clear reference to NBC’s peacock logo.

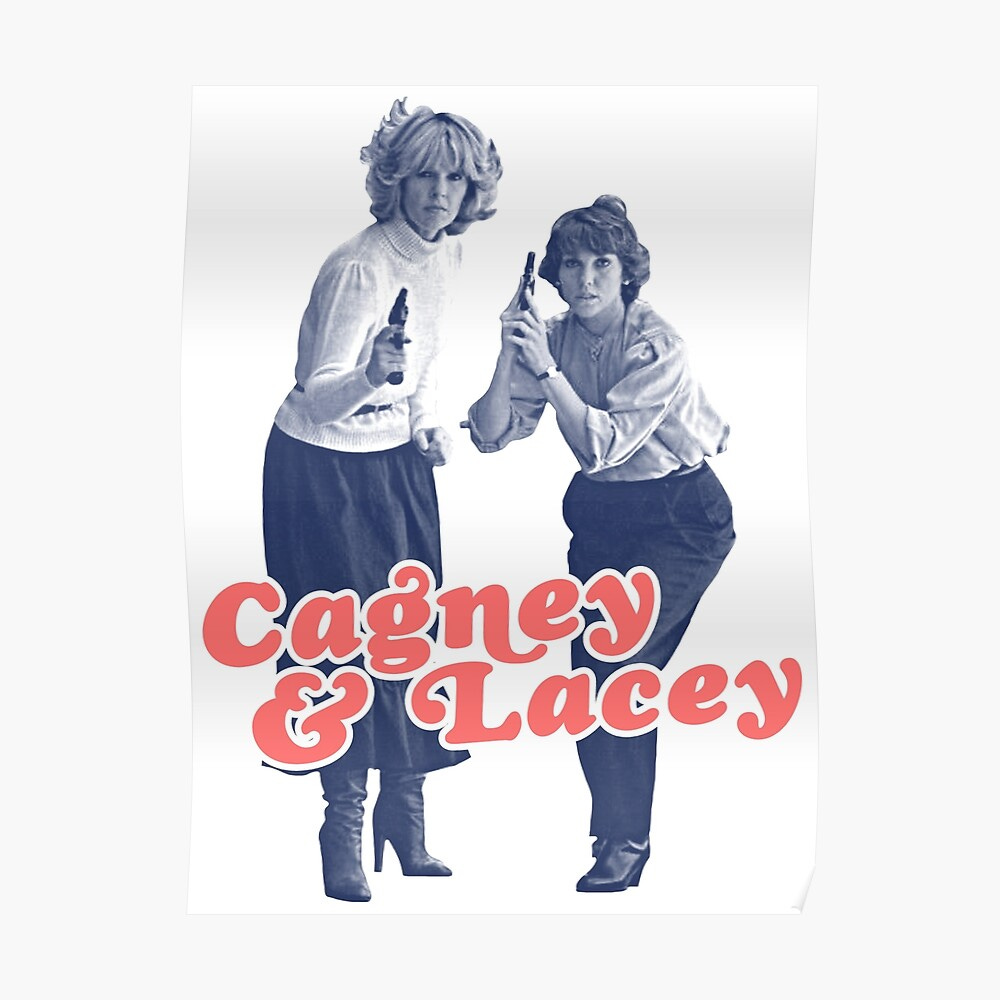

Cagney & Lacey: Media Narratives Around Fandom and Organized Leveraging of the Community

The 80s saw another fandom invited to keep their show on air. When CBS announced that Cagney & Lacey was cancelled, executive producer Barney Rosenzweig believed that if enough complaints were made, they might stand a chance at being resuscitated. It had worked for Star Trek, right? Rosenzweig told Ms Magazine that he personally pored over fan mail and wrote each fan back, asking to take part in the letter writing campaign that was aimed at both the network and the press. While about twenty thousand letters were delivered to the network, Rosenzweig believes the headlines had more of an impact, and was free publicity for the show.

Dorothy Swanson, one fan who was eager to support Cagney & Lacey, created the organization “Viewers for Quality Television” just for that cause. When the cancellation was reversed, VQT expanded to boosting other shows that needed assistance. The elite undertone was intentional as they sought to promote only what they considered to be quality television shows.

VQT was embraced by the entertainment industry because of the organized support they could provide, and the clout their seal of approval would carry among other viewers. When VQT created awards and planned conferences they never lacked for industry heavyweights to participate. It was a mutually beneficial relationship.

Grassroots Fan Efforts

Of course, there were fan campaigns that existed outside of VQT’s purview. Most of these have been forgotten, but Swanson complained about them on record, so we do know they existed. She said, “It's frustrating watching them dilute our effectiveness.” When Cagney & Lacey was rescued, the number of letters received was unprecedented.

Now other fans were doing the same thing and spoiling it.

Fandom Moves Online

By the late 80s, fans had started to congregate online (in other words, fan communities are as old as the Internet as we know it). They connected with people from all over the world who, all the same, shared their deep devotion to The X Files or Due South or ‘NSync. The early online landscape saw fandom sprout anywhere communities could be formed: message boards, comment sections, quiz sites, forums, dedicated fan sites, blogs, mailing lists... There were no platforms created specifically for fans, but like weeds growing through cracks in the pavement, fandom found a way. It still does.

I joined fandom in this online wave, and as an international fan with a love for American television, I was at the mercy of my local networks picking up series I loved. But the online world kept me in the loop: we knew when a show was at the risk of cancellation, and there was nothing stopping us from participating in fan campaigns.

International shipping fees were a low price to pay for another season of your favorite show.

Of course, the growing number of online spaces that fans claimed as their own attracted the attention of industry. Early on, lurking was an essential fandom management tool; today, there’s social listening software now available for a mid-range price.

Henry Jenkins’ term ‘convergence culture’ summarizes this cultural shift: old and new media co-mingling in unexpected ways, influencing one another. When industry, whether that’s creators, producers, investors, performers, tap into fandom spaces they are entering an existing ecosystem. It doesn’t qualify as breaking the fourth wall, but it’s close, like eavesdropping under an open window, and using what you learn to your benefit.

Don’t Kill Your Gays, Staff Writers

Here’s an example of the dynamic I’m talking about: staff writers would visit forums and had discussions with fans—maybe reassuring them that their favorite lesbian couple, for example, wouldn’t be killed off. Only for the show to go on and kill one of the characters, leaving betrayed fans in its wake. While this scenario might seem oddly specific, it’s has already happened twice.

In the early aughts Buffy fans, specifically those who were passionate about the Tara and Willow relationship, had been reassured by staff writers that they had nothing to worry about. They weren’t going to cop to old media cliches. Trust had been established with these insiders, but it was lost when a major plot point involved the death of one of them. Not only had their pairing been separated, but the Kill Your Gays trope had been used once again.

More recently, the CW show The 100 followed the same blueprint.

Concerns were mounting among the Clarke and Lexa fans. The show runner appeared to be attached to the pairing, but rumours were spreading that a major character death was imminent. When the fan unrest became known, show writers sought out the niche forums where these discussions were held to pacify the fans. And when the narrative of the show unfolded, killing off one of the pair, a pattern was repeated on more than just the screen.

This time the backlash made a lot of noise. Fans hashtagged their way onto Twitter trends for 12 days straight, and their fundraising resulted in a forty-thousand-dollar donation to the Trevor Project. An apology was delivered from the show runner on Twitter, but the damage had already been done.

If anyone was actually sorry for something it likely was for the failure of fan management, not an ill-conceived plot device.

Fans vs. Everyone Else

Self-aware fans know that they are not the primary audience for any given content but watching the wheels of publicity grind separates fans from the regular audience. (Which might explain why, as everything converges into fandom, it seems like the people who truly are “the fans” get the most attention.)

Fandom studies have long discussed that fandom relies on not facing the commercial nature of their fan object head on, lest it taint the emotional bond fans have with it. But the more attentive fans are, the more difficult it is to ignore the commercial aspects.

One Tumblr fan said, “I don’t necessarily feel used, I feel marketed to.” In this case it isn’t seen as a negative. Being a marketable demographic is validating to some, it can be seen as an acknowledgement of fans’ importance to the brand’s success.

For other fans, the very same tactics will be seen as “baiting,” or manipulation.

This disparity of perception reflects how diverse fandom is, and despite shared devotion and a deeply felt connection with fan objects, fans and fandom do not act as one. This is particularly notable with properties that invite speculation on behalf of the audience. Because fandom is spread out over multiple platforms, with people who have incredibly varied entry points, backgrounds, knowledge bases the diversity of thought is unending. Looking at sub-fandoms where fans splinter into groups based on fan object opinions reveals where narratives diverge for different fans.

The Impossibility of Appeasing Fans

This means that it’s nearly impossible to appease fans with one piece of media; because the final product will prove some people right, and some people wrong. Matt Shakman, director of Wandavision, recently guested on Kevin Smith’s podcast they discussed the difficulty of dealing with fan theories from a creator’s perspective. Each new episode was a chance for more unintentional clues to be picked up, and days in between were long enough to develop the theories further, and further. The map is being read but the compass is wrong.

Some of Shakman’s quotes were picked up and syndicated but framed in a way that suggested edits had been made to deny fans the satisfaction of being right. A Tumblr post calling out this method has just under eighty thousand notes; those notes are from a diverse group of people, fans of the show, anti-fans of the show that are pleased they’re messing up, fans of other properties looking on, surprised that a show would insult fans in such a way.

What the people who interacted with that post probably won’t do is listen to the original interview, and some will bring up this very post when arguing with someone about how Wandavision treats its fans.

Fan Management and Human Brands

Fan management is difficult enough when it comes to creative properties, but when dealing with human brands, the complexities and variables multiply. The human factor cannot be underestimated, on all sides. When complaints are made about toxic fans, the context is often cropped out and motivations are flattened. We’re told fans are too powerful and celebrities are drunk on power, directing their armies with Twitter likes and emojis and watching the battleground from afar.

But fans aren’t mindless; they are devout.

One of the conclusions from Troika’s fandom report is that brands need to focus on identity rather than lifestyle. Brands should, “embody the identities of those who buy into them and create a social connection between those who share their beliefs.” Ironically, the brand, or fan object, is coincidental in the equation. Fans overwhelmingly feel ‘chosen’ by their fan object, not the other way around. Much like a deeply held belief, the how and why can be hard to verbalize; it just is.

Fandom researchers and academics have long pointed to the similarities fandom shares with spiritual communities. The devotion avid fans show to their fan object is a purposeful, fulfilling act. But if we recognize that fan devotion can be analogous to faith, we must remember that where there are believers there are also apostates. We must recognize that as with faith, there are those who are more devout, more strict, more fervent in their evangelism, and that devotion can wax and wane within individuals over time.

Those who self-identify as stans are those most likely to feel this way, and it’s why the intensity with which they can turn on people is so frightening. The loyalty is not to the brand itself, but what fans ‘know’ it represents; a knowledge that has as many variables as there are fans. It’s why the tension between what fans want and what business does is escalating, and why more and more people are finding themselves in the crosshairs. The behavior might not be stoppable, but it can hopefully be understood.

God tier stuff here.

My research is related to how K-pop fans relate to digital fandom spaces. Right now, I'm moving towards Digital and Technology Policies, because I strongly believe there's a sizeable fandom burnout coming caused by the insane levels of devotion and emotion harnessing that became standard in the industry, _especially_ concerning the fan-specific platforms. Policies is likely the field where all of this might hopefully be handled or at least regulated. There are questionable devices to help protect innocent people from religious charlatans but there are allegedly strong customer protection rules that should, ou could, be doing something about this... At the end of the day, besides the multiple worst-case scenarios we can probably conceive about fatigued, apostate fans, there's simply the fact that countless careers won't stand the test of time without steady support.