Last week my Twitter account was hacked, and I was kicked out of it within minutes. I received very little help from Twitter Support (read:none). The account now boasts some sort of Legends of Zelda spam, with all my older tweets deleted already, so I’ve now abandoned the idea of returning to that account. I’ll miss my bookmarks most of all.

(There’s probably a joke somewhere in there about being exiled from the Twitterverse, ha-ha.)

My first tweet on my new account attracted bots and spam accounts galore, probably the mention of “hacked” because that’s all the bots were talking about. DM this guy. Go to Instagram and DM this guy. My account was saved by so-and-so, DM them.

Absolutely overkill for that tweet, from an account low on the totem pole, no less, which highlighted the absurdity of all the responses.

I might recommend that you try it, and tweet about being hacked just so you too can get a first-hand experience of being courted by bots. It’s always a good reminder that social sites are not only the domain of people.

The monetization of fandom has long been on my mind, and I’ve looked for ways to frame it to make sense of it all, but I read something this weekend that really stuck out to me in its simplicity:

"Kids are bypassing their own imaginations, substituting prepackaged, commercial characters and story lines for their own creative efforts. […]Not only is the media the storyteller, but it's also supplanting and perhaps inhibint the ability of children to tell stories of their own."

—The Other Parent, James P Seyer

This book is explicitly about children and the effect of marketing on them—it’s from 2002, so perhaps it even foretold the grown-ups of today, myself included. I was obsessed with The Lion King and asked my artist father to paint what would qualify as fan-art back in the day.

And that was the 90s, before our very existence became a landscape of narratives and intellectual property pushing itself on us. Before character studies have been replaced by spin-off limited series, when visual media is filmed and framed with consideration for gifs and virality, when historically ‘anti-fanwork’ franchises now host fanfiction challenges.

Perhaps it’s why there’s such a strange new fandom generation that wants to be handed content, recommended content, and served content rather than going looking for what they might like.

There’s no diminishing that cohort, so those of us left behind will have to abandon ship or be fastidious in our community and culture building. We’ve been for sale for longer than we ever would’ve thought.

The ad-driven, for-profit site Fandom.com serves as a type of encyclopedia for media, peddles the data they’ve collected from site users as FanDNA. Users are placed into one of four slots depending on how they engage with the site, begging the question of what users are actually fans of.

Campfire, a marketing agency, has three fan categories, the skimmer, dipper, and diver, differentiating by the depth of investment. The Campfire founders were behind 1998’s Blair Witch Project, and it has allowed them a unique perspective on how fans will build their own communities if given the right tools. They see their role as “designing an experience” rather than pushing content to individual fans.

“Once every conceivable surface has been taken, advertising’s growth can come only at the expense of our own.”

The communal experiences are what makes fandom. There are two primary relationships, with the fan object, but also with each other. You’re supposed to opt-in to fandom, fandom builds the infrastructure for fans and content for each other.

But there is no opting in anymore, we have to opt-out, and with much effort.

Tumblr has remained a primary home for much of creative fandom because of the user-control involved. You curate your feed, it’s chronological, and any algorithm in use can be avoided with some userscripts and avoiding “recommendations” but even Tumblr is experiencing a drought.

The decreased engagement with fandom content has been complained about for years, and while I’ve noticed it too, in my case it’s more related to my status as a pariah than anything else. If someone accidentally reblogged something of mine or my other fellow castaways, they would be told immediately that they were supporting the scum of the earth.

Perhaps that in itself has led to a more cautious approach to reblogging—sharing content. I’ve wondered about that, but it seems to be a much more widespread problem than just in my corner of exilees.

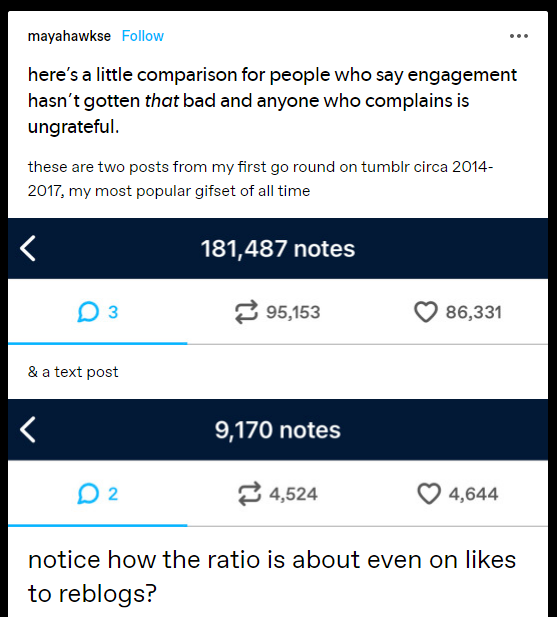

A recent post on the matter, is below:

What has been theorized a lot—and can be seen in the notes of the above post — is a theory that this has come from Twitter and Instagram refugees who don’t realize that “likes” don’t mean anything on Tumblr. On other platforms “likes” can increase the visibility of posts, on Tumblr it serves only as something of a bookmarking feature for the user who does the liking.

And that’s really one of the big problems; the skewed ratio between likes and reblogs illustrates how posts can be throttled and kept at bay.

I think we’re already at the place that was described in Carrie McLaren’s STAY FREE #18, included in Punk Planet’s May 2003 edition. The title of her piece alone is a question: “As advertisers race to cover every available surface, are they driving us insane?” Can we answer that in any way other than yes, yes they are driving us insane? Perhaps we could add that we, ourselves, are also driving ourselves insane. “Once every conceivable surface has been taken, advertising’s growth can come only at the expense of our own,” and it has.

We participate in our own commodification on the daily, so it shouldn’t be surprising that we’ve backed ourselves into a corner where we are competing with billion-dollar franchises trying to replace creativity with officially sanctioned bibles and spinoffs.

What may start happening on Tumblr is the use of the Blaze feature that allows you to pay to get your post forced onto people’s dashes, increasing the possibility of spread. If you’ve spent months on a novel-length fanfiction or hours on a gif set, it might make sense to spend a little money to possibly get some traction. But in the grand scheme of things, this creates a new hierarchy and the direct monetization of fandom content.

I cited a Blaze experiment conducted by user elodieunderglass in a previous piece, where the result was less than impressive. But elodieunderglass already has a large following, so it might make sense that the organic reach of her posts would be greater than the result of her Blaze Campaign.

I can easily picture users resorting to Blazing their content across dashboards to get exposure, and I can easily picture the backlash that might cause in some communities. But displeasing some corners of fandom never leads to much, not when there’s money on the line and corporate hovering, trying to increase revenue.

Hi Monia,

I'm doing some research around what it means to be a fan today and how that concept might be evolving, and I was wondering if you'd be open to having a conversation about your own experience as a (exiled) fan and some of the ideas you have been writing about on your Substack? If so, let me know and we can try finding a good time to talk. Thanks!

Great work as always!