A context capsule of today's fandom climate

As reported on by Fandom Exile.

Welcome to new readers and longtime subscribers. Over the past year, I’ve been documenting how today’s fan culture evolved - from Livejournal to stan Twitter, from grassroots movements to corporate influence.

While fandom and stan culture is not something everyone needs to know about, if you’re interested in the (d)evolution of fandom and the way audiences behave, as well as how industry interference has influenced behaviour, you’ve come to the right place.

This post is a barebones timeline and refresher to contextualize future writing, and for a base understanding of today’s ecosystem.

Digital Fandom History

A lot of people credit and/or blame Tumblr for the current fandom dynamics and online climate, but Tumblr was a result of what came before. Online environments work like all other environments, building and evolving from the past.

The ecosystem that Tumblr created was influenced by Livejournal. Before that, online fandoms primarily existed on mailing lists. Forums frequently hosted fan communities, but as they were isolated islands they were more likely to absorb changes from outside rather than spread their dynamics.

Discussions about the shifting landscape of online fandom were being had as early as 2003. Livejournal user prillalar explored the difference between mailing list fandom and journal-based fandom, explaining that a mailing list was insular, “content flows into it, but doesn’t flow out -- it’s all in there, and it doesn’t mix with all the other mailing list bubbles.” In contrast, journal based fandom allowed content to wash over you.

Journal-based fandom centered around users themselves and content became transitory, flowing through your feed. You would absorb a lot of content that you weren’t necessarily interested in, inherently cross-pollinating topics across networks.

This user-centric interface is the most common online today. Many argue this contributed to the proliferation of the so-called “main character syndrome” (more on that later). There’s been many think pieces about how narcissistic and antagonistic we’ve become as a result of this self-centered social media. Livejournal users were not immune to this phenomenon.

This new interface brought on a shift in fannish behaviour, moving away from single-fandom into multifannish behaviour, because your fandom participation wasn’t siloed in insular communities; everything shared the same space and the same importance.

Part of why Tumblr has been so influential is the frictionless landscape of endless content, and while Livejournal wasn’t as bad—there was no reblog/retweet/restack function, so posts remained static and didn’t breach containment—you would still be exposed to so much more content than you originally signed up for. Following people meant learning about their interests. It was easier to dabble in multiple fandoms simultaneously—which to me was always the “healthiest” way to fandom because it meant your attention and investment were diversified and not tied to a single community or tribe.

In a way, the new Substack model is a mix between mailing lists and the journal/blog model. (If we ignore notes, which we really should.)

The shift from gated and isolated fandom communities to the borderless open internet meant that the fourth wall that was so necessary for fandoms to operate well disintegrated. With the growth of emo band fandom (aka bandom), the subjects were tech-savvy gen-Xers and millennials that shared the same spaces as fans and interacted with them. As one fan pointed out,

“Bandom has no history, and the teenagers for whom this is their first fandom vastly outnumber the people who even know what a mailing list was. Not to mention the live canon and the RPS thing and the four hundred meta issues that I've never seen mentioned in any fandom before. (What do you do when an RPS subject replies to fic (directly, on LJ, logged into their own account) with "dialogue rings true"? WHAT?!)”

This is how feral fandom became a problem.

Fandom Goes Feral

Feral fandom sounds like an insult, but it’s an old term used to refer to fandom that springs up separately from organized fan communities, independently of fan-created structures and outside the spaces that inculcate people into community norms and traditions.

I’ve pinpointed three lynchpins for the acceleration of this unmooring and dissolution of traditional fandom communities into a more loosely connected network that primarily is attached to the fan object: Ohnotheydidn’t and the online gossip complex, early social media that explicitly busted the fourth wall such as Buzznet and FriendsOrEnemies (FOE). And finally, the normalization of fan fiction for profit, in great part courtesy of One Direction HQ.

OhNoTheyDidn’t (ONTD), the crowdsourced celebrity gossip community, was a big part of expanding the online gossip footprint. It blended all types of celebrity content and pop culture news, marrying fandom and celebrity watching and spirals of speculation.

Speculation is engagement, so it makes sense that it would be promoted and that fan theories would be catered to. For over a decade, a site called Gossip Cop acted as the PR mouthpiece to refute (or confirm) what was being gossiped about online and what tabloids were reporting.

In a meta moment, a 2011 New York Times article on stan culture was shared to the community, tagged with the comment, “lol this is a respected newspaper? how bored do you have to be to write an article on stanning anyway jfc,” as if the community itself wasn’t responsible for normalizing and amplifying the behaviour that warranted this type of coverage.

Buzznet and FOE were both similar to MySpace, but also functioned as a proto-Instagram; photos and videos were shared, and you could make “friends” (or enemies, in the case of FOE), and there were equivalents to influencers in the form of scene kids, and band members were active and accessible to an insane degree. Preteen and teenage fans were in regular communication with band members and their entourages on the sites.

Bandom was essential to mainstreaming real person slash shipping, in part because of the access that fans and fan objects had to each other, and because this access was framed as a mutual relationship rather than an asymmetrical parasocial fan ↔ fan object/brand relationship.

As mentioned earlier, it wasn’t unusual for band members to comment on explicit fan fiction that they were featured in. It was a game, of sorts. Some sought to keep a semi-private line of communication with their fan base where corporate oversight couldn’t reach. Fall Out Boy’s Pete Wentz was a pioneer when it came to that, with his multitude of online journals/blogs targeting different parts of his fanbase.

Fanfiction for profit has existed under the radar for a long time, but in 2012 we reached a tipping point. Yes, it’s when the Twilight fan fiction Fifty Shades of Grey was thrust into the mainstream, but it's also when Real Person Fiction (RPF) was folded into official business strategy.

One Direction (1D) was still a new band in 2012, but they were already big business. A sixteen-year-old girl’s 1D fan fiction was picked up by Penguin, and she allegedly said, “I’d really love [One Direction] to read my book when it comes out, though! That would be nice.”

Expressing the desire to break the fourth wall is a violation of fandom norms, illustrating the feral nature of the new fans. Not only are you not supposed to profit from fan fiction based on existing characters, or worse in this case, real people, you absolutely, categorically should not want them to engage with it.

Before feral fandom burst through all erected barriers, RPF was recognized as taboo in most fandoms. It existed, but it was kept under wraps to limit the risk of exposure to the people depicted, but also because fandom at large found it disrespectful. This is where I circle back to ONTD’s role in all of this: celebrity gossip requires a lot of narrativizing, and from there, graduating to outright fiction is natural.

A year earlier, Sony Music teamed up with Wattpad to produce official 1D fan fiction in the form of “a five-part Valentine’s Day-themed story with each chapter detailing a date with a member of [One Direction].”

Wattpad itself has become a big player in the mainstreaming and monetization of fan fiction. They made it their mandate to funnel fan fiction into traditional publishing and then the big screen.

Even beyond business entities and HQs now, monetization of fan fiction is coming from the masses, with outsiders selling others’ fan fiction on Etsy and TikTok, because, why not? Fandom’s participatory culture and gift economy have been fully railroaded and run dry. Where we go from here remains to be seen, but I’m not optimistic.

Stan Culture Rises

I’m a broken record when it comes to this, but I like to differentiate between fans and stans. The two operate very differently, even though at a glance they may look the same. Stan culture is, by default, toxic. I sometimes refer to communities of stans as standom to emphasize that these two modes are inherently different. Fandom is pro-social, standom is anti-social. Fandom regulates internally, standom attempts to exert control externally. Fandom is capable of ignoring critique because it has nothing to do with their enjoyment of any given text. Standom needs critics to fall in line, to mirror their perspective.

For stans, it isn’t enough to enjoy something because of your own experience with it: your positive feelings have to be reflected at you, infinitely. And if they aren’t, then your fan object is underrated and this needs to be rectified. The naysayers need to be put in line.

Fandom used to be good about letting people enjoy things and letting people dislike things. I miss the fandom of yore where the term “squick” allowed you to express a personal dislike without making a value judgment on others’ appreciation. Back then, you could say you weren’t interested in a particular couple (or in fandom lingo, ship) because you just weren’t, no need to source ethical and moral concerns that may prove hypocritical and require intense mental gymnastics when a ship you do like has the same unethical and immoral flavours.

When someone tried to remind people of old school “laws of fandom” in 2016, the reactions revealed how different the fandom climate had become. The responses were antagonistic and angry. Fandom didn’t change online environments, it was the medium, the environment itself that changed fandom.

Fandom used to empower fans to create their content to carry on when they were let down or the source text was completed. Stans are too reliant on industry feedback and too aware of the zero-sum nature of the present cultural ecosystem to take their toys and go home. They now rely on cowing dissenters into submission, no matter the cost.

In theory, you can dislike something, but you shouldn’t make it known because it immediately becomes more than just your personal opinion. It taints the climate, and that is unacceptable. This is a result of the scarcity mindset, the winner-take-all approach that has become standard in standom. If there isn’t endless praise and acceptance, what you love will be taken away from you.

Within the current system, to be a good fan is to advocate for your fave, within fandom and outside of it. The loudest voices are not interested in letting people enjoy their faves; they are acolytes for their own, and beat the drum for homogeneity, as long as it works out in their favour.

But is opting out even possible?

The way industry engages with fandom encourages this type of attachment. It’s the melding of the attention economy with the affect economy, resulting in the superfan economy, which the next section will cover.

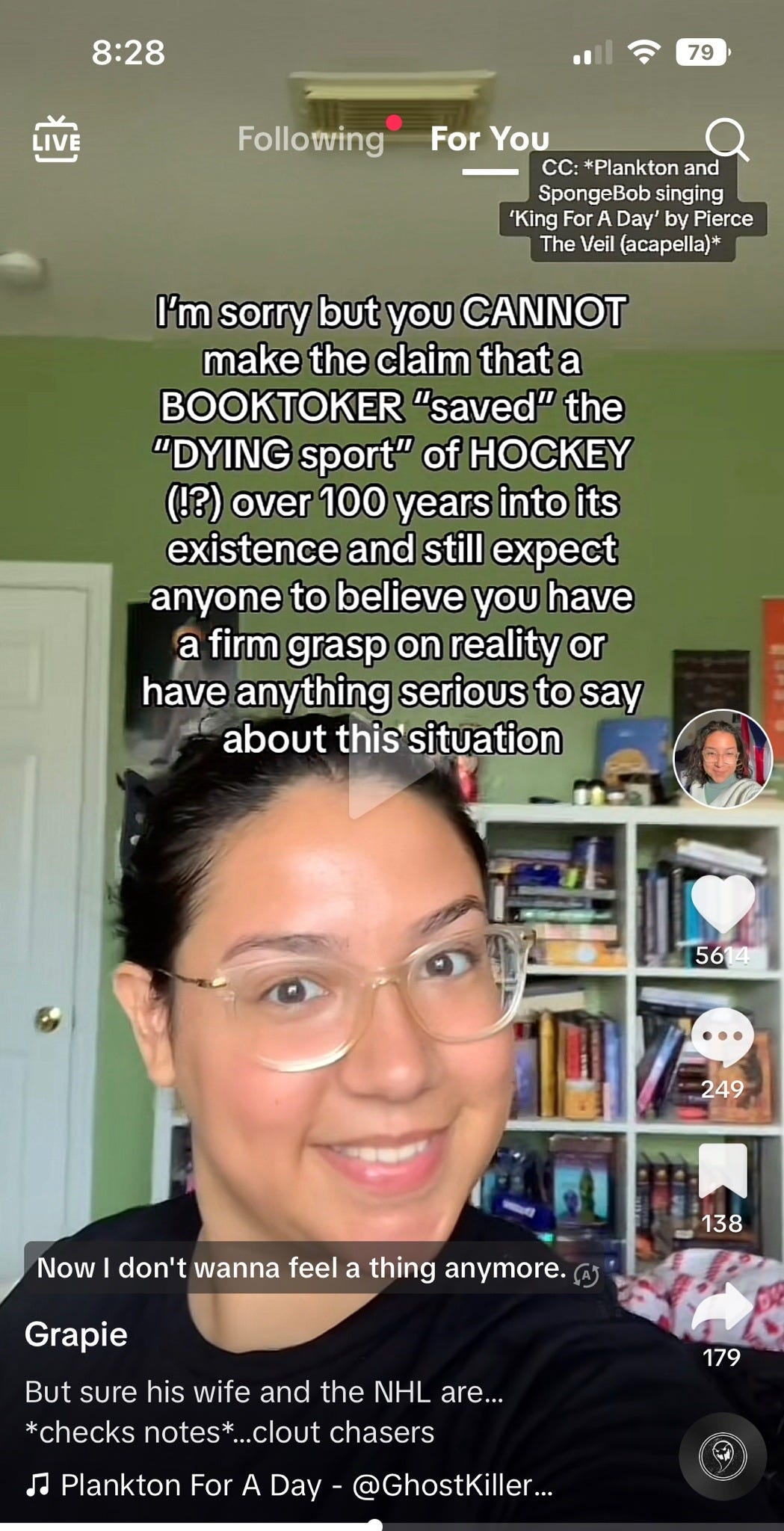

The damage that can be caused by stan culture and this type of attachment isn’t limited to music or media fandoms. When hockey fandom collided with Booktok, things went sideways, fast.

A new NHL team leaned into the online attention their players received on Booktok They ended up courting some of the big accounts by engaging with their posts, but also flying them out to multiple games and gifting them customized merch.

The problem was that the fan-created content was sexual in nature, and was unwelcome to some of the players on the receiving end.

While there’s nothing wrong with that type of content, the official team shouldn’t be endorsing it. It questionably blurs the lines. What is appropriate in fandom is not necessarily appropriate elsewhere. Emily Rath, an author who spoke out against what the team was doing said it well, “You should not treat your employees with the same level of abstraction as the fans do.”

The people who are on the receiving end of fannish activity and attachment are referred to as “fan objects” for a reason: they are objects to the fannish community at large. But they shouldn’t be objects to the people that are supposed to have their backs and that profit off of their work.

Engaging with fan content and participating in fandom activities seems like a good idea on the surface. But there are trapfalls all over the place that can sanction bad behaviour, if not outrightly reward it. Of course, that means it will persist, emboldened.

The Superfan Economy

I’ve been calling the infrastructure of online spaces fandom greenhouses because of the way the mediated relationships mimic the fan ↔ fan object relationship that is the basis for fandom communities. Parasocial attachments are the norm, and inevitable. And when communities build around that, we start to see nascent fandoms and the creation of fan objects from things that traditionally would not qualify as fan objects.

The communal aspect is incredibly relevant to the fandoming of everything because it isn’t just about customer relations, but about developing “relationship management systems” (also known as standard fandom management).

One-on-one targeting isn’t enough because the audience isn’t static, it is made up of multiple sub-communities that organize among themselves and have their rituals and norms, and these communities aren’t static either.

But fandom communities are not profitable when their primary attachment is to each other rather than the product. The loyalty has to be shifted to the brand or fan object: it must be totemized. This is the desired escalation from an ideal customer or mere fan to the preferred: advocates, evangelists, fanatical loyalists, and zealots. Or simply, stans.

As mentioned earlier, the trope is that the super-online have main character syndrome, but fans are willing spectators. Followers can get their main character fix by proxy. As

said, “It’s only necessary that there’s a main character at all.” They don’t have to be the centre of attention, they can simply come along for the ride. Cheering from the sidelines can also be euphoric. Fans derive intense satisfaction from supporting their fave.But this is a deliberate commodification of affect. No one wants to acknowledge that the flip side of this devotion is backlashes. Intense attachment and investment are not always positive. When so-called “fan armies” are sought out, those in charge don’t consider that these armies might one day turn on them. By the time that happens, it’s too late. They’ve been enabled and encouraged to make a ruckus, and it’s only when you’re on the receiving end that you realize the mistake that was made in empowering them.

When the NHL team that engaged with fans withdrew and cut them off, there was a widespread uproar because the fans felt used. The below screenshot illustrates the disconnect between how fans saw their contributions to hockey fandom in general and reality.

I’ve covered the heckler’s veto expressed by a dissatisfied audience, but also the shattering of idolatry and those emotional ramifications. Yet, as it stands, I’ve barely scraped the surface of the way fandom ecosystems have developed and been maintained.

So, stay tuned for more investigation into what happened upstream of today’s culture. I’m still knee-deep in research for my deep dive on Buffyverse fandom. Its place in the timeline of shifting fandom environment and fan service and fandom community management is fascinating. There was even a documentary about how the cast and crew interacted with the fandom online over twenty years ago.

I’m also working on pieces examining if fandom mainstreamed trigger warnings, fan labour, the fandoming of politics, and some stuff that hits closer to home.

Great stuff as always. Nodded along furiously to this: "Fandom used to empower fans to create their content to carry on when they were let down or the source text was completed. Stans are too reliant on industry feedback and too aware of the zero-sum nature of the present cultural ecosystem to take their toys and go home."

based & technological determinism pilled

In all seriousness, this is all great stuff. Looking forward to learning more about the Buffy fandom; it was a phenomenon that I was *aware* of, but never knew much about.