The mainstreaming of slash fandom.

Once a taboo perspective, profitability changed the game.

Celebrity gossip has been part and parcel of the publicity game since its invention. It benefits industry and celebrities themselves, at least if they have a proper team who knows how to steer through the labyrinth of press, fan speculation, and behind the scene hurdles. The publicizing of relationships has been a common tactic to draw attention; narratives, stories stick. Heck, it’s been twenty years since Britney Spears and Justin Timberlake split, yet we can count on the press bringing it back when convenient. People still care what they have to say about each other because the relationship was amplified, coaxing audiences to care about the romance long past its expiration date.

It shouldn’t be surprising, then, that fandoms have developed a focus on ships—short for relationships—when it comes to fan text, whether it be fanart, fanfiction, and speculation. With the increased visibility of fandom, this engagement has been a gold mine for those paying close attention.

Many people will have heard that 50 Shades of Grey started off as Twilight fanfic and cycled through the blockbuster book to big-budget film trilogy. It’s not the only crossover, though, there’s also The Mortal Instruments, which was originally published as a Harry Potter fanfic. It spawned graphic novels, a film adaptation, and a Disney distributed TV series. The most recent mainstreamed work of fanfiction is the After film trilogy, inspired by One Direction, it has ushered in Real Person Fiction (RPF) into the public sphere of profitability.

The monetized properties are all part of the “het” genre of fanfiction, meaning the primary focus is on straight relationships. RPF of this kind is often maligned as the sphere where self-insert fiction resides, whether in the form of “Your Name” style fiction that allows readers to insert themselves into the story, or with a so-called Mary Sue. Mary Sue is an idealized, infallible character that sometimes acts as an extension of the author, something of an aspirational Manic Pixie Dream Girl.

The more fandom and industry coalesce and influence one another, the farther we’re getting from what fandom used to be. And it’s not fandom’s fault, not entirely, as the lines have been crossed by the other side, with a wink and a smile. Louisa Stein, a researcher of millennial fandom pointed out, “The mainstreaming of fandom does police and punish certain fans, modes of fan engagement, and modes of fan production, while heralding others.”

If we’re going to take that at face value, it would be easy to say that straight couples and the focus on them are what’s is being heralded, which isn’t entirely wrong. Slash, which is what same-sex relationships are referred to, is also being engaged with, but on a very different scale.

My knee-jerk suspicion is that franchising a gay love story may still be too risky, especially for worldwide appeal. After all, it might limit the consumer goods and licensing deals that are relied on for maximized profit. But there are other ways to profit off fans’ slash fantasies beyond franchising, and independent actors have been doing it a while, now.

There’s a different approach to Real Person Slash (RPS) but that it is being approached and appropriated is impossible to deny. I’ve referenced the independent art exhibit where One Direction fan art was blown up, and erotic fanfiction was acted out by performance artists. But that is small potatoes when looked at with a broad lens.

There are far bigger players on the scene, and they have exponential budgets to spend. The way that fanbases are interacted with have changed, as has the fandom climate itself.

Slash as a phenomenon has existed for longer than there has been a word for it. The term itself originated with Star Trek: The Original and its fans. Fanfiction often being centered around relationships, friendships included, there needed to be a differentiation between stories that were romantic and those that were platonic. This was navigated by replacing the ampersand binding two names together with a slash, Kirk & McCoy becoming Kirk/McCoy. That’s how, well, slash was born.

My fandom life didn’t start with slash, but I knew it existed. I had encountered fanfiction while exploring a Buffy the Vampire Slayer fansite, curious about what the stories section was all about. The fic I recall most vividly was a short femslash piece with Willow and Buffy. It opened mid-sex scene, soon revealing that Buffy was under the influence of a spell. It might’ve been tagged appropriately with accurate warnings and keywords, but I likely wouldn’t have understood what it meant at the time.

As a first encounter, the fanfic didn’t really whet my appetite for more but had I read something different, with more setup, I might’ve been seduced right away. It didn’t put me off fanfiction or Buffy, but I came to the conclusion that these non-canon relationships weren’t for me.

Roswell, my first real fandom, had three will-they-won’t-they couples from the get-go, enough to keep an unimaginative viewer like myself occupied and uninterested in non-canonical relationships, slash or otherwise.

It wasn’t until I got into the US adaptation of Queer As Folk that I sought out slash fiction. I had watched the English original, a Russell T. Davies penned half-hour dark comedy with a total of 10 episodes.

As a teenager myself, I was drawn to Charlie Hunnam’s Nathan, the 15-year-old who heedlessly ventured onto Canal Street and the world of adults led by his libido. His primary conquest and the man he would continue to pursue throughout the series was the 29-year-old Stuart.

The age gap was a risque choice even at the time, I question whether it would fly today. As a teen myself, I wasn’t too concerned with the ethics of it all, happy to vicariously follow along from my living room. A particularly scandalizing scene featured a post-funeral blowjob in someone else’s childhood bedroom. It was enough to know I should probably keep my viewing habits to myself.

Despite following the show religiously, it didn’t inspire me to rush to online forums or fan sites. It seemed too adult even then, and the limited source material didn’t help. I hadn’t expected to get into the American adaptation at all, just like the naysayers who had said an explicit gay show would never make it to air in the US. I didn’t think the show could ever compete with the original, or mature into its own.

It caught me at just the right time, and instead of making new friends in a new city, I quickly caught up on all five seasons of the show. The age difference between the main couple was reduced by a hefty two years, and many plots were recycled, but the show had so many more episodes, enough to mature into its own and detach from the original.

The fandom was still vibrant even on the heels of the final season being finished. There were plenty of stories to catch up on, headcanons to consider, and fans to meet. The fandom also had a hidden corner of RPS, where the lead actors were paired together, but by the time I dabbled the heydays were over.

This was an in-between time when RPS was still underground and unwelcome in general fandom communities. But the genre had been growing in popularity over many years, through many iterations of online communities and fandoms. At this point, it was too late to put the lid back on.

“You dumped [a fandom] into the Internet and a year later, it was a hundred times bigger, and a year after that, it was hundred times bigger, and a year after that, it was a hundred times bigger. The growth was so exponential that the culture that had been transmitted was swamped by the newbies. And everybody felt like they had just lost control of their culture.”

— Cynthia Jenkins, Fan Fiction Oral History Project (2012)

Three specific fandoms can be credited with the normalization and spread of RPS. Lord of the Rings, Supernatural, and Emo Bandslash/Bandom all swept through online communities, picking up new shippers along the way.

The male cast of the Lord of the Rings trilogy became fandom favourites and resulted in quite a few cast ships flooding fan spaces. The RPF fandom was supposedly responsible for popularizing the term “tinhat.” Born out of a disdain for fans that truly believed certain actors were dating and were unwillingly closeted the plan was to, “come up with a snappy sobriquet for the hardcore tru believas who spread all the rumors.” Tinhat was the term that stuck, but the derogatory term didn’t have an impact on the popularity of the ships. The website Datalounge which hosted the tinhat discussions ended up banning them from the forums entirely.

To this day tinhat is used to refer to fans who believe that there is a real romance between two fan objects. Not exclusive to same-sex pairings, but less frequent with straight ones as it is harder to justify why the relationship would be kept out of the limelight without the history of closeting to rely on. Still, The X-Files, Outlander, Twilight, these are all properties where fans believe a straight relationship is being covered up, for one reason or another.

When Supernatural premiered in 2005, a large fandom presence was immediately noticeable. That it wasn’t exactly the audience the show had been looking for was also noticeable, especially over time and as the concept of fandom was tackled on the show, leaving much to be desired in the realm of tact.

Demon hunting brothers didn’t make for the best romantic pairing, so many fans focused on the actors themselves, and a potential relationship between them. RPF was still a contentious subject, but it wasn’t as disturbing as incest. Nonetheless, and not without consistent protests, the fictional Winchester brothers still became the stars of so-called Wincest. With the introduction of more regular characters in later seasons, other fictional ships gained ground, but the RPF never slowed down, and it provided a fertile ground for more fandoms to grow.

Bandslash and Bandom were natural terms for emo fans to adopt, but they weren’t the first to call their music fandom by those terms. It was a topic of heated discussion during my time, so I feel obliged to acknowledge it. The wave of emo bandom was more like a high tide exacerbated by seasonal winds, but earlier bandom had undeniably made a mark.

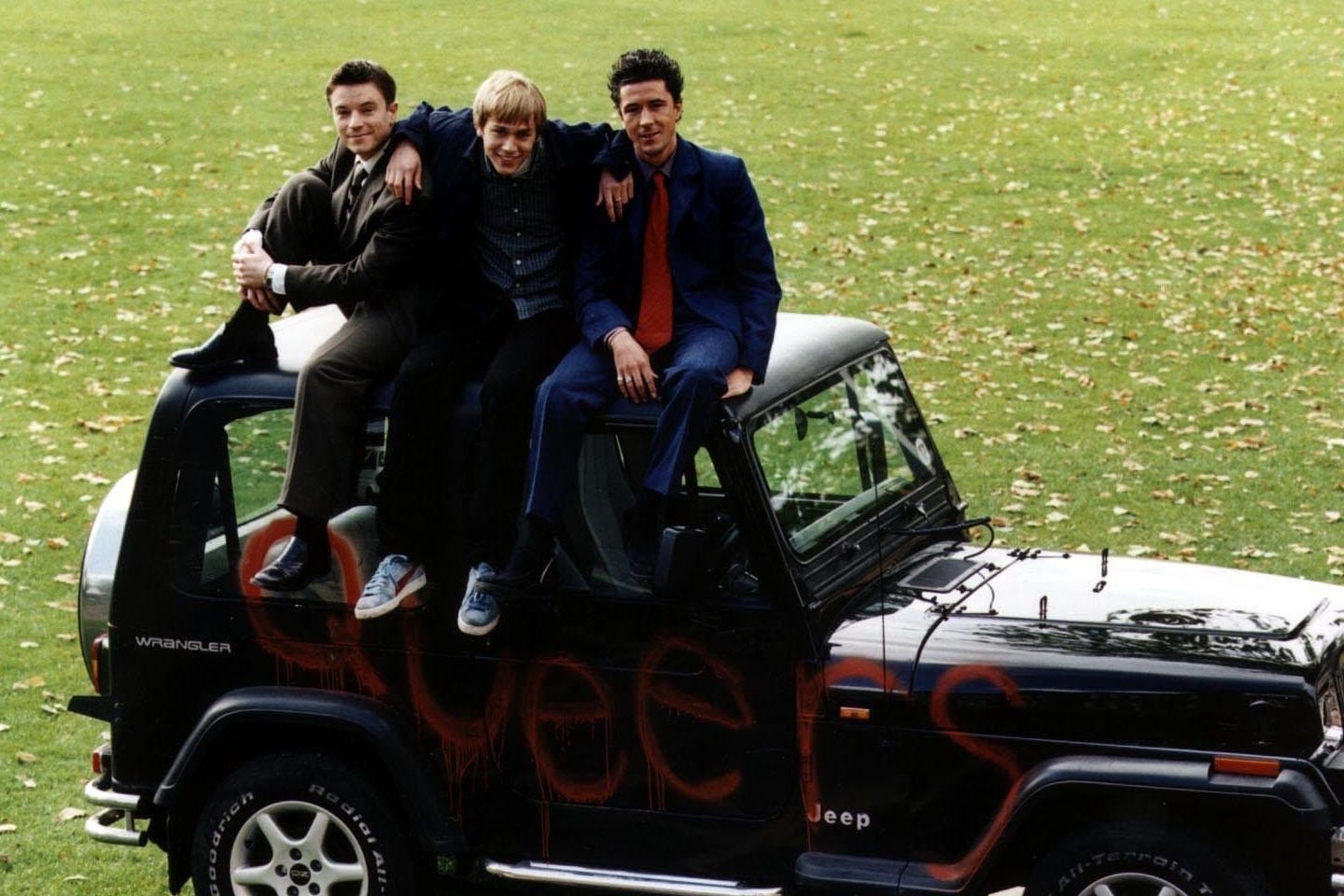

The music magazine NME published a piece on indie rock-centric bandslash in 2005, a few years before emo hit worldwide recognition. The bands included The Libertines, Kaiser Chiefs, Franz Ferdinand, and others, and expressed support when confronted with the topic. Alex Kapranos of Franz Ferdinand was asked multiple times about fanfiction, and told Chartattack in 2004,

“There’s absolutely nothing wrong with fictionalizing a genuine character as long as you make it clear that you are fictionalizing, which I think all that slash stuff does. I think it gets dangerous when people start believing that those things are actually true, and I think for the obvious majority of people that that’s not going to be the case.”

In other words, tinhats not welcome.

Emo bandom was large and sprawling, but there were three core bands1. Unsurprisingly, these three bands all had simultaneous mainstream success. Fall Out Boy (FOB) and My Chemical Romance (MCR) were on similar timelines, both forming in 2001, albeit on different sides of the country. The third band, Panic! At the Disco (PATD), was brought into the limelight by Pete Wentz of FOB. PATD also endured the most drastic changes since then, currently still active but as former lead vocalist Brendon Urie’s solo project. None of the other original members remain.

While intraband pairings were the biggest and most popular, what made bandslash unique was the amount of crossover and cross-pollination between bands. With a large number of bands sharing a record label and long and large tours allowed for frequent different interactions between band members. With multiple bands active at any given time, there was overflowing available content. From video diaries to online diaries and secret blogs, to interview crossovers, and stage antics.

Fandom communities seemed to grow exponentially every night and the influx of new fans was chaotic, stunting the usual group acclimation. This process of fandom overwhelm was described in Superfandom: How Our Obsessions are Changing What We Buy and Who We Are2, “When groups grow too large for top-down policing, it’s up to members to internalize the group’s social norms and guard each other from breaking them.”

I’ve no doubt that the ubiquity of celebrity gossip had a massive impact on rapid growth. Blind items invited speculation and intentionally dropped clues, sites like OhNoTheyDidn’t shared a platform with the most active fandom communities, on occasion even breaking news about a fan object and becoming the ground zero for fandom spirals. Among other things, ONTD was responsible for leaking Pete Wentz’ nudes and photos of Gerard Way and Lindsey Ballato’s impromptu backstage wedding.

The influx of fans created a stark divide between originals and the newer cohort. New norms emerged to suit a larger community. As the audience numbers increased and the stages grew larger, none of the bands under the bandom umbrella seemed concerned with slash fans. Their tactile behaviour, sincere praise of each other, genderbending, and stage innuendo neither ceased nor went into overdrive. It seemed as if they were unaffected by the intent analytical gaze of fandom.

As their platforms grew some fans started to believe they were being queer baited and started categorizing homoerotic or suggestive performances as “stage gay,” and even confronted the bands about it.

In one way the accusation was that the on stage performance was indeed a persona, as Way described. It meant the behaviour was intentional rather than emotively driven. It was intentional but developed under an entirely different context. When FOB were cutting their teeth on the Chicago hardcore scene and MCR were doing the New Jersey punk basement circuit they were faced with entirely different audiences. These were not spaces overflowing with acceptance, and homophobia was a common occurrence.

The crowds were brash and crass, homophobia and sexism not uncommon. Wentz kissing his lead singer every show and proudly wearing women’s jeans and “guyliner” was not appreciated. It became a habit to purposefully incite the audience and challenge perceptions.

As late as 2007, MCR faced hostile festival goers at Download, their headlining performance opening to “a volley of bottles, batteries and basically anything else that could be launched with force.” Fan reports from the show said the audience became disruptive, shouting homophobic slurs towards the stage. It was in response to this that Frank Iero interrupted the performance of “I’m Not Okay” by planting a sloppy mouth kiss on Way’s face. It was a challenge to the audience, a confrontation.

Way described his attitude in Spin in 2010, “I wanted to challenge gender, abuse the audience. I didn’t want the girls to want to fuck me, I wanted the straight guys to want to fuck me.”

The attitude towards fandom and fan works continued to be mostly positive, allowing for a reprieve among fans who feared a backlash for real-life shipping. Slash fanfic was a tool to tell stories, many that couldn’t be found elsewhere. They were but characters populating the stories, and writers weren’t trying to manifest new realities. The primary concern at the time was that the band members get that, and it seemed like they did.

Shipping was was one cornerstone of fandom, but it didn’t define, nor was it a marker of identity as it is nowadays. Neutral online spaces existed, and I personally was never aware that some people really believed in the ships when I was in the fandom, which just goes to show how effective the compartmentalization was.

A decade ago, fans would be distressed to discover a band member crossing into fandom spaces, particularly when they left comments in their wake, which almost exclusively occurred in response to porny fanfiction. Sometimes fans broke the fundamental rule of not sharing fanworks with those depicted in them. That was bad enough, but if the content was sought out, was it really any better? It was a reminder that there were few ways to fully shield yourself from the outside world, and that we couldn’t expect the outside world to abide by our rules. All that could be done was, “learn how to integrate our existing mores and modes of interaction into this new paradigm.”3

It seems very naive looking back because it presumed fandom would only really be interesting to the fan objects themselves. But that’s far from accurate, isn’t it? How else can one explain the way media and industry have embraced stan culture and egged it on, shipping and all? How else can one explain that fan text—any and all of it—so frequently is picked up and regurgitated, or even repackaged and resold?

I witnessed all of that first hand with “Larry Stylinson,” the main, but far from the only, ship featuring the One Direction band members. The pairing of Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson was incredibly popular in the fandom throughout the band’s run, topping Tumblr’s Fandometrics Year in Review in 2015, and 1D itself was second on the list of most popular bands on the site.

These results were reported on as if being of actual significance. Perhaps it’s because they are significant, just not in the way fans might want to think. To top a list like that is like a beacon to those looking for easy marks.

How else can one explain Vanity Fair publishing multiple columns over multiple years penned by Richard Lawson, featuring what can only be described as real person fanfiction;

“Well, obviously, Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson are meeting with caterers and picking flower arrangements and deciding how long the cocktail hour should be after the service, but once they’re done with all that, and are back from Tahiti, they’ll have to do something big. Maybe go on a world tour performing The Last Five Years together.4 (Louis, that Shiksa goddess.)”— Vanity Fair, 2015

In 2016 both 1D and the Larry ship had slipped to third place according to Fandometrics statistics, and by 2017 they were out of the top 20 entirely. You’d think it would signal an end to the shenanigans, perhaps, but nearly five years after 1D split, HBOs Euphoria went ahead stoked the embers.

One of the episodes in the first season spotlighted Larry fandom through Kat, one of their characters. It also included an animated sex scene between Styles and Tomlinson. Why not go all out, I suppose?

One of the show’s co-producers went so far as calling it a reward on Twitter.

In order to nail the episode, fandom was researched thoroughly. A Tumblr account was created, set up as if actually run by the character, Kat. But contrary to a low-grade stunt, this account hadn’t been created just in time for the episode to air, instead, it predated even the series premiere.

No one knows who was manning the account during the long period it was active, but it very obviously was not a 17-year-old girl, just another shipper in a sea of shippers. It’s just good old manual data mining, isn’t it?

Some fans remain aware of the distance between fandom and industry, aware of the purposeful, playful crossing of lines. They know that they’re being observed and catered to, that it’s no secret to anyone in the industry that, “there are fan followings based on a perceived closeness on the part of the fans, and they play it up to drive their fans to a near frenzy.” It works, and it has worked for a while, now.

“As devotional fandom has become increasingly visible and mainstream on social media, a dependable source of ‘co-creation’ for media brands looking to enhance the value and versatility of their products, tinhatters push this sort of production beyond the horizon of usefulness.” — Olivia Coy, Fifty Shades of Yellow, 2015

Coy is correct that tinhats, stans, and other fervent devotees have pushed beyond what seems useful. But usefulness is not a requirement when content mining is growing. It will require diligence from fans and fandom to recognize that their visibility causes them to be a part of the media cycle, even a bullet point in targeted marketing campaigns. The dynamics that have already played out will continue to, the cycle self-perpetuating indefinitely.

It’s open season, and there’s no getting out of dodge.

I would argue that The Used were influential to early bandslash in the normalization of homoerotic performance. They never crossed over fully fandom-wise, especially after the rift with MCR. The Used were also founded in 2001, in Orem, Utah. Bert McCracken, the lead singer, had left home and lived with the guitarist. There was a large Mormon community. By default, their performances of homoromanticism & gender bending were used to transgress.

Superfandom: How Our Obsessions are Changing What We Buy and Who We are, 2017, Zoe Fraade-Blanar & Aaron Glazer

FairestCat on Livejournal, The Long-Delayed Fourth Wall Meta, April 1, 2008

The Last Five Years, Jason Robert Brown’s 2001 musical.

Feel like I need to yell “ITS HABBENINGGGGG MONIA IS TALKING ABOUT SLASH” before I actually read this post.

I don't know if you'd call this slash fandom or not, in that it's a new exporation of historical materials by smart next-generation Beatles fans and by historians and historiographers. They (mostly women and decidedly not the widely recognized major authors) are taking a fresh look at Lennon and McCartney's real-world love story. Without forcing a label onto it, and without prurience, they posit that the partnership was different than it has been canonized since 1970. Because anything at all redolent of homoeroticism, or physical closeness between men, truly was closeted in the 60s and 70s, there are loads of observations that can be made of existing footage, quotes, and songs, which show that L and M's story (and their split) was a lot deeper, and even the opposite to, the canon "Lennon got bored." In fact his enduring love for McCartney was in plain sight and is, thankfully, being analyzed through the open minds of the next generation.

This is totally aside from real-person fictional L/M stories that I suppose have been going on forever.

And it's pretty hard to imagine that the surviving Beatles and the estates of the other two are going to monetize this new perspective. They are heavily monetizing re-releases of old material, though, for sure.