Astroturfing and early fan-(in)fluencing

The flip side of fan empowerment.

"We feel like people need to understand how powerful their voice really is. We also want to steer and control what happens in the marketplace."

— Dave L. Balter, BzzAgent founder1

Astroturfing is the term used for covert advertising presented as organic word-of-mouth; these are “grassroots” campaigns that have been funded and managed with an ulterior motive. The illusion of a large group of people in agreement with the message, whatever it may be, is part of the sell. Word-of-mouth, peer-to-peer, cyber street teams all fit the bill when it comes to methodology and intent.

I wasn’t familiar with the term itself until One Direction fandom where it was occasionally evoked when opinions and narratives that went against fandom core beliefs and expectations were spread. The most shared reference was a Tedx University of Nevada talk by Sharyl Attkinson, it’s a concise explainer of astroturfing, but it narrows in on corporations, lobbyists, and special interests groups, which are a universe away from fandom activity.

Because of this, the claims that fandom was being ‘turfed often came off as paranoid to me. It was a great way to shut down follow-ups and dismiss matters entirely, and there was no way to prove it. The paranoia could be harnessed to strengthen the group identity, as well as draw lines in the sand as to what topics were untouchable. It was also a great way to cast doubts on fellow bloggers, accusing them of being industry plants and pushing an agenda. In one way, the practice of astroturfing was used by bloggers as a way to discredit opposing views.

“The key is empowering fans to go out and sell this music. They already do, but we say, 'Let's give them focus.’ Instead of having some promotions guy out there hyping the hell out of it, we try to keep it as real as possible and still create a good word-of-mouth campaign.”

— Dave Neupert of M80 Interactive Marketing for Billboard2

The online campaigns that gained popularity at the turn of the millennium were predated by street teams that quickly became an essential part of any album launch. Rich Isaacson and Steve Rifkind are credited with introducing and popularizing the street team concept for music promotion with Loud Records in the early 90s. This technique cut out the middleman allowing them to sidestep industry gatekeeping and get straight to the audience, allowing them to spread the content among themselves.

Thanks to an FTC report released in September 2000, we know that the music, film, and gaming industries all leaned on street teams to push products and brands. The report was prompted by speculation that violent entertainment had played a role in the Columbine High School shooting of 1999. The focus was specifically on how adult and violent content was promoted, and whether industry leaders were following their own guidelines and rating system: they weren’t.

The FTC report found that minors and children were explicitly targeted and sought out in marketing plans for 80% of R-rated films; 70% of violent games rated Mature; and a full pot in the music industry, with all 55 explicit records seeking a teenage audience.

“One plan stated ‘an aggressive street marketing campaign will be key.’ Others plans similarly stated that ‘an aggressive street team campaign will be in effect to support and complement our set-up’; ‘We will plan to initiate an aggressive street marketing campaign to maximize visibility’; and ‘This type of guerilla marketing through these web sites will bring enormous visibility to... audio and video releases.’”

— Marketing Violent Entertainment to Children: A Review of Self-Regulation and Industry Practices in the Motion Picture, Music Recording & Electronic Gaming Industries, September 2000

There reasoning behind the focus groups targeting 10-12 year olds, was provided in a memo from the National Research Group about research for I Know What You Did Last Summer:

“Although the original movie was R rated and the sequel will also be R rated, there is evidence to suggest that attendance at the original dipped down to the age of 10. Therefore, it seems to make sense to interview 10- to 11-year- olds as well. In addition we will survey African-American and Latino moviegoers between the ages of 10 and 24.”

This was far from the only R-rated film being surveyed among pre-teens as young as 9; Disturbing Behavior, Judge Dredd, Enemy at the Gates among others. All studios were guilty. Nickelodeon ad buys were attempted to promote The Fifth Element, which was denied and appealed by the studio because “This film needs the audience that Nickelodeon provides to be successful.”

While these approaches have been described as lapses of judgment, I don’t think there was much thought beyond the bottom line. Teens, pre-teens, and children have been a ripe market for advertisers for a very long time, the widely held mantra is that hooking the kids gets you brand loyalty for life. So of course, they would be primary, desirable targets. When everyone else participates, abstaining puts you and your product at a disadvantage. There’s also safety in numbers: if they all do it, it’s hard to single out one bad actor.

Because the focus of the report was adult content, there’s no way to know how much street marketing and online word-of-mouth were used for all the other content that was being produced. There’s no reason for those promotional campaigns to have any less effort put into them. That’s what really stands out to me about the report.

Beyond the entertainment industry’s in-house marketing, there were plenty of consulting companies set up to take advantage of fan enthusiasm. Companies that specialized in this type of cyber word-of-mouth marketing included; Electric Artists M80 Interactive Marketing, Fanscape, Knee Deep Promotions, Real Street Promotions, BzzAgent, and P&G’s Tremor. All were fighting for a limited amount of teen eyeballs and emotional connection in the early aughts.

"Teens are one of the most disempowered groups out there. They are filled with great ideas, but they don't think anyone listens to them."

— Steve J. Knox, Tremor

This was also when “brand management” was predicted to shift to “cohort management” according to Forrester Research because of the internet. It’s one of the ways affinity-based groups have been fostered and fandomized; by adjusting messaging by interest group their existing expectations will be reinforced. Sometimes the messaging might even be contradictory for two separate cohorts (stan wars, anyone?)

Different cohorts—communities, affinity groups, subfandoms—will respond to different messaging, and sometimes, “that won't survive in the mass market,” Tremor’s Ted W. Woehrle explained to Forbes in 2004. At the time, Tremor boasted approximately 280,000 teenagers on their books, allowing for a wide variety of messages to be tailored to a wide variety of niches.

“The mass-marketing model is dead. This is the future.”

—James Stengel, P&G’s global marketing officer

Electric Artists were hired to expand the messaging for the Sylvester Stallone vehicle Driven. It was a shoo-in for action and Stallone fans, but teenagers might not respond to that. Marc Schiller explained they decided to push Stallone’s co-star Estella Warren among the teen demographic. Success came when they found a way to make the product relevant to their target cohort, to “put the products into contexts relevant to the people talking in those communities so that they can continue talking about the products to their friends and coworkers.”3

Much of the reporting on the companies and marketing successes talks about fans being “hired” and “paid” but the reality is most of the work is done in exchange for merchandise and contest entries. Agnese Vellar looked into the local Italian music fandom where there was plenty of street team activity as well. This highlights that these efforts are in no way exclusive to the US market.4

Vellar documented official portals that organized missions to keep fans occupied. While the thought is that these are fans working to support their favourites, the way these missions and “calls to action” are set up are ultimately for corporate profit. Some missions included promoting lesser-known artists that shared a label with the main fan object. Other activities encourage buying multiples; “fans had to download multiple times [sic] a song from iTunes. For each time that they bought the song they scored 20 points, that would be converted into gadgets or other prizes.”

The positive spin is that even though the labor is free, fans who participate can still “acquire cultural, social and symbolic capitals which they are then able to convert into economic capital.” This is overly optimistic in my view. All of this “capital” is tied to the particular community it’s performed in. The internal fandom hierarchies don’t exist elsewhere, they cannot be translated into another community, and social capital is only as real as the community allows it to be.

I’m not sure how helping other people make money is “empowering” —especially when it relies on emotional and affective economics. Vellar compares the official corporate-backed activations to fan-initiated projects and they are similar, but not the same. I’ve participated in multiple projects and campaigns trying to make up for the lack of official backing. Turns out fans and stans have far less impact than we’d like to think, something that will be covered in greater detail at a later date.

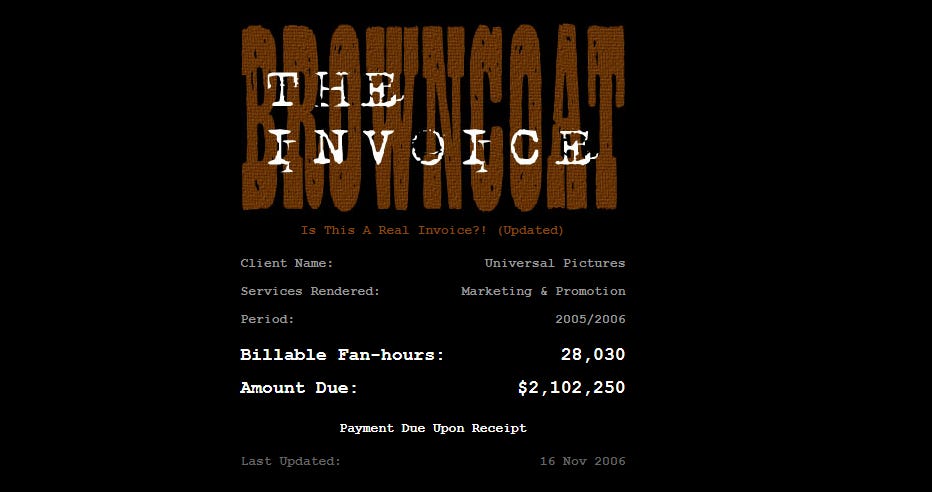

Problems also arise when the fandom activity doesn’t live up to corporate expectations; one notable example is that of Universal Studios and their attempt to collect retroactive licensing fees from fans who had participated in promoting the film Serenity.

Vellar uses the term “participative stardom” as the approach most label marketers have, which is a term that works extremely well to describe stan culture and the second-hand euphoria that can come from recognized success. It's no different from sports fans who celebrate their teams’ win.

Stans still receive credit and favorable coverage from the press, as defined by Fader “stans are responsible for composing a high-strung concentrate of love and competition that maintains the relevance of an artist even in the absence of their art.”

That’s what outsiders would like to think: that stans’ emotional connections and intense effort is ultimately self-effacing, done for a greater cause. It’s not wrong per se, but the greater cause that fandom believes in isn’t the dollar amount in the corporate checking account. That causes friction, and I personally can’t help but suspect the intense backlashes are in part a result of all the meddling. We can’t count on industry or even the humans behind the brands to tame extreme stans because zealotry is good for the bottom line.

“They think they’re going to save money; they think they’re going to get something for nothing. And then they kind of started figuring out, ‘Oh well actually they have a mind of their own, and they’re going to say what they want and do what they want, and we can’t control them, and it’s not really free media.’ It’s kind of a different—it’s a problem, a different communication problem.”

— Merrick McCormick of Campfire as quoted in Mel Stanfill’s Exploiting Fandom5

Kid Nabbing, Melanie Wells, 2004, Forbes

Online Consultancies Spring Up To Assist Labels, Net Firms, Doug Reece, 1998, Billboard

Kellogg on Integrated Marketing, Dawn Iacobucci and Bobby J Calder editors, 2003, The Kellogg Marketing Faculty and the Faculty of Integrated Marketing Communications at the Medill School of Journalism

The recording industry and grassroots marketing: from street teams to flash mobs, Agnese Vellar, 2012, Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies, Vol 9, Iss 1

Exploiting Fandom: How the Media Industry Seeks to Manipulate Fans, Mel Stanfill, 2019, University of Iowa Press