Fandom Warfare

Anti-fandom, narrative control and the authenticity of organized hatred.

Last week, Rolling Stone published an exclusive on a report from AI publicity firm GUDEA that looked at the narrative around Taylor Swift’s latest release, more specifically, the spread of discourse that claimed her latest era was right-wing coded. The report was allegedly spurred on by an in-house Swiftie who thought the spread of the discussion seemed “inauthentic” and RS drew the conclusion that the discussion was “seeded and amplified by a small network of inauthentic social accounts.”

The term inauthentic does a lot of heavy lifting, and the accounts are later referred to as “accounts behaving more like bots than human users” which really stuck out to me. The article didn’t go into much depth about the data, so I sought out the report on GUDEA’s website. Frankly, it left me with more questions.

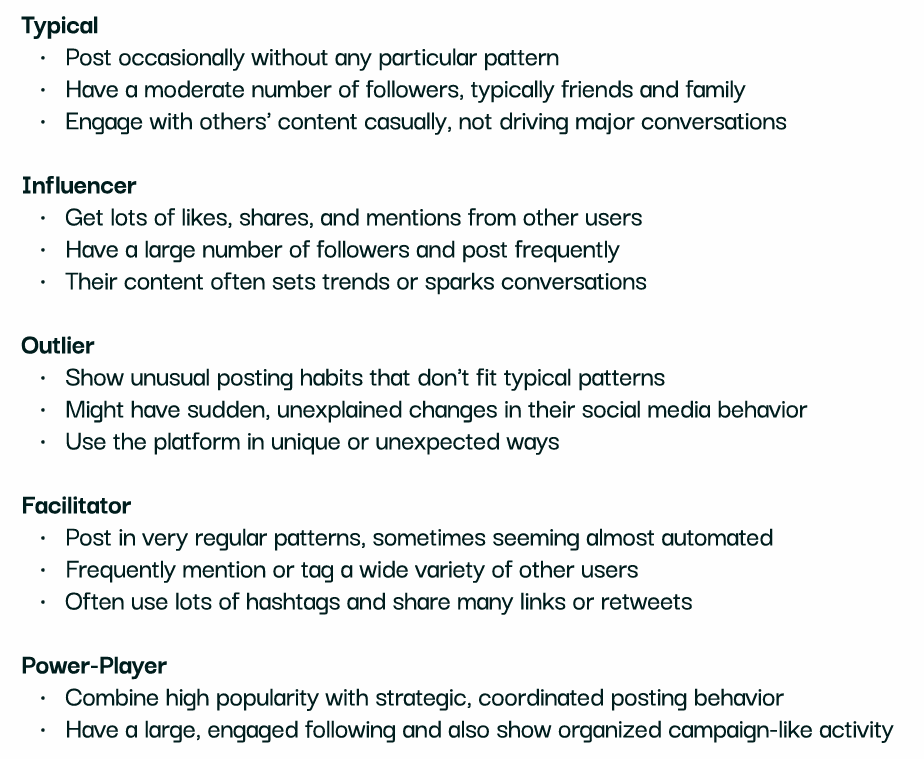

In the report, accounts are identified based on posting patterns. ‘Typical’ users are those who post occasionally without a pattern. There is no atypical user, just so-called ‘outliers.’ According to the report, the ‘facilitators’ are the accounts that would be considered bots, yet their participation never got above 0.4%. Bots are not mentioned in the report at all, but based on RS’s reporting and the syndication of this report, we’re supposed to infer that outlier accounts are actually bots. I’d like to know more about the patterns they discuss and how this expressed itself across the 14 platforms they looked at. While bots are very prevalent on X/Twitter, I find it hard to believe there’s a lot of them on TikTok or Instagram, especially if we’re looking at posts. Are comments and original posts weighted equally? We’re not told.

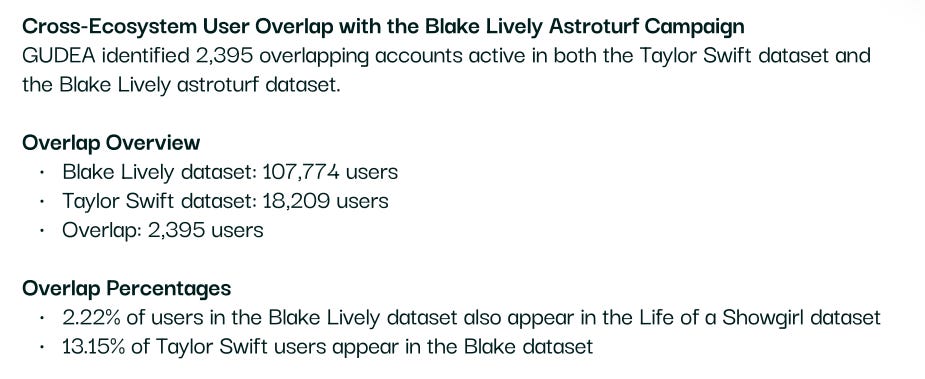

Calling it a coordinated attack implies that there is a specific source behind it. The report insinuates that TAG PR was involved by bringing in Blake Lively. Considering the two of them have overlapping fan bases, and as a result, overlapping anti-fans, it doesn’t surprise me that there’s an overlap in users, but it’s a much smaller overlap than I would expect.

Lively and Swift have been linked for years, which means someone who dislikes one of them may also have negative associations with the other. If anything, the astroturf dataset being six times larger than the Swift set shows how much larger of a scale that was operating on—then again, there’s no information about how that dataset was obtained, what time period it covered, what platforms it was on. There’s also no control group.

The RS article closes on the claim, “there’s no reason to assume” that anyone who engaged in the discourse was sincere. It’s a bold assertion that makes very little sense. Of course, there are plenty of drama farmers, trend surfers, trolls and contrarians who jump into discourse based on the engagement they can elicit, this statement outright dismisses the very real phenomenon of anti-fandom.

Anti-fandom sentiment is a massive part of culture, and it’s what makes so much of the discourse toxic. I don’t see the point in dismissing the sincerity of these actors. The intensity with which you see devotion can be matched with antagonism. Reactive and proactive anti-fans are all over the internet, and they have far more targets than big name celebrities.

We can probably differentiate between proactive and reactive anti-fandom; offensive and defensive positions. Are they seeking out targets to abuse and harass, or are they reacting to perceived slights?

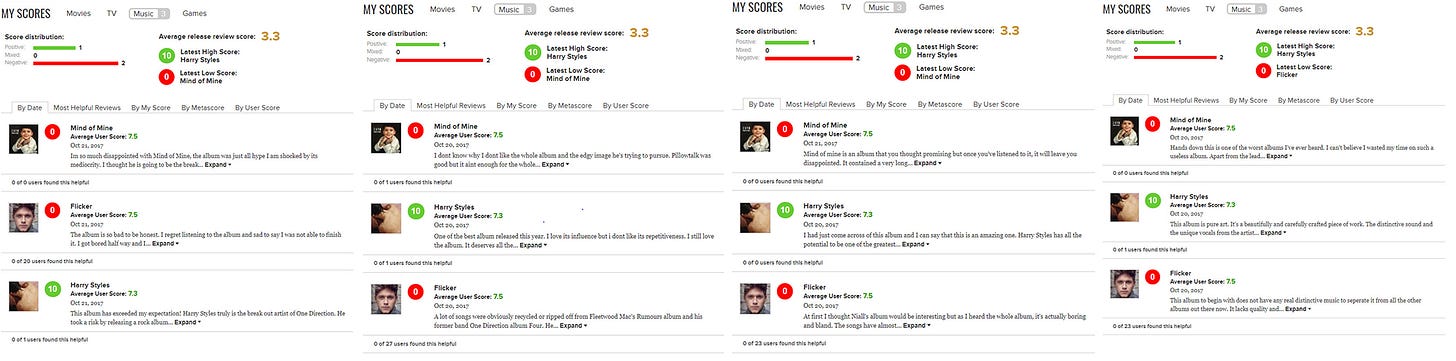

One of the most organized and persistent anti-fans in One Direction fandom is a Harry Styles fan who has spent nearly a decade mocking and denigrating his former bandmates. Following them as closely as a fan account, but with the purpose of railing against them. They also seek out fans, stalking and harassing them, creating sock-puppet accounts to continue to do so after being blocked. I’ve been on the receiving end of their abuse, and had the misfortune of seeing their bizarre rantings. This account is a proactive anti-fan.

The primary function of the account is actually to be pro-Styles. Being an aggressive, persistent anti-fan of his former bandmates is a fundamental part of that identity. Simply enjoying the content that they receive isn’t enough. For these fans, Styles’ superiority needs to be litigated and asserted by going to war against his bandmates. Because HSHQ official accounts amplify and reward accounts that engage in this type of anti-fandom activity, and because the media has been happy to participate, this behaviour is perceived as being sanctioned and appreciated. This emboldens the behaviour and is seen as approval. It becomes seen as part of the job of being a fan; engaging in this type of behaviour is seen as supportive.

Swifties themselves participate in proactive and reactive forms of anti-fandom, I would argue they’re pretty known for it. In HBO’s Bad Blood: Taylor vs Scooter, a journalist who was interviewed mentioned being targeted because she isn’t effusive enough, despite being a big enough fan that she’s participating in the documentary. A recent Substack piece discussing “performative activism” noted that Sabrina Carpenter was facing backlash from Swifties. Recently, Josh Hutcherson was asked if he was a Swiftie, and he said no, something that set off her fans. That’s not even touching on the way the men associated with her are often dragged. From fake videos and rumors being spread about Joe Alwyn to “increase hype” to harassing Scooter Braun.

And to be clear: this is not a Swiftie exclusive thing. The majority of them do not engage in this type of behaviour, but those that do are incredibly driven to make their voices heard and can, indeed, coordinate attacks and make a real attempt at influencing discourse.

In other words, the idea that a coordinated attack means the sentiment behind it is inauthentic is a massive oversimplification that ignores the very real antagonism that exists in fan spaces.

While the report positions this as an attack on Swift herself, I think we shouldn’t ignore how often anti-fandom is about attacking fans. Impacting a celebrity—a fan object—is not really feasible, but you can make their fans miserable. You can force them into defensive posturing and force them to engage in ridiculous claims.

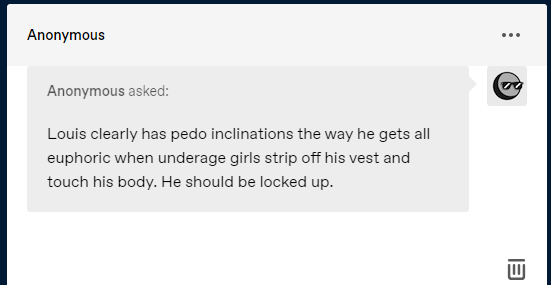

The discourse can be swayed via update accounts, secret chats where big name fans coordinate, and it can be seeded via asks and goading fan accounts to respond. Anonymous ask features are used a lot for this, a feature that Tumblr offers, which is one of the reasons fandoms were so vibrant on the platform. The anonymity is essential to shaping discourse and slinging accusations. It could be trolling, malicious rumour spreading, antagonism, or officially seeded narratives—the spread of these can be coordinated, too. When the same ask is received by multiple blogs, it’s referred to as a “trotter,” someone who is trying to get people to engage and spread a particular conversation.

Basically: coordinated, persistent and long-lasting forms of anti-fandom antagonism aren’t new. It’s not something that can be dismissed as inauthentic automatically.

It is worth asking whether these activities have been amplified by companies and actors that have skin in the game. For example, HBO’s president of programming ordering staff to create sock-puppet accounts to harass critics is more damning than anti-fans banding together to do the same. One comes with institutional backing, with money and profit on the line, and the other is driven by authentic antagonism. If TAG PR or another firm hired by someone wanting to muddy the discourse and antagonize Swift fans, it’s absolutely worth knowing. But the report doesn’t prove that. Even if actual bots were involved, anti-fans can set up bots, too, just like regular fans can. Anti-fans can likewise organize and have elaborate networks of sock-puppets to engage in malicious communications.

The problem comes with dismissing all anti-fandom sentiment as inauthentic. In a way, that too is a form of narrative control. Ever since the report came out, there have been droves of Swifties who accuse critics of being bots or paid for as an easy way to dismiss their commentary—even when it’s not unfounded or extreme.

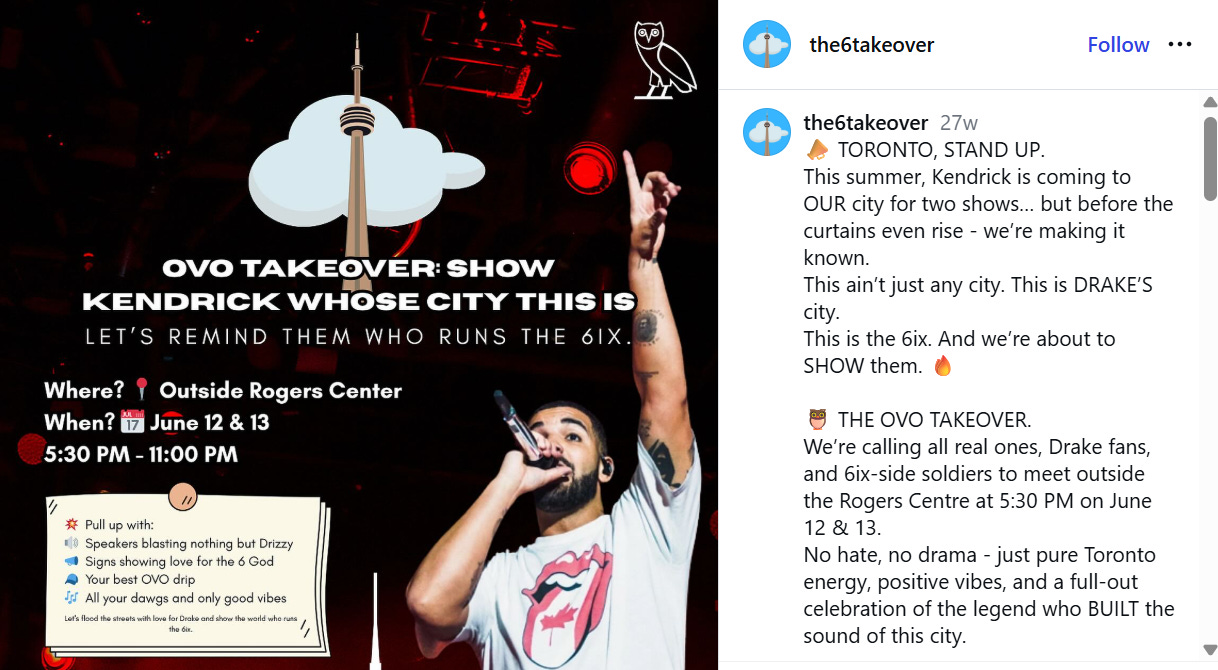

Ultimately, this report is an advertisement for GUDEA as a firm. They are selling their abilities to control narratives and intervene “before crises take hold.” They are selling the very coordination that is being criticized. And I wouldn’t be surprised if part of the approach to combat these crises is seeding anti-fandom against perceived opponents. If that sounds too conspiratorial, consider how fan wars have been encouraged and coordinated by official sources for decades. I’ve covered the way positive influencing has been coordinated, as well as the antagonism that is intentionally fostered. Considering that, it makes sense that this type of cultural engagement would take off and be perpetuated. It feels good to bond over hatred, over a common enemy, even if that enemy is a former bandmate or ex-boyfriend.

The broader point of the report, urging fans not to engage with seemingly bad faith criticism, is worthwhile common sense. But for me, that would also go for positive coverage. Is it a coincidence that RS received this exclusive when they served as a central hub to promote Swift’s latest release? Is all their positive coverage authentic despite being coordinated? Skepticism and scrutiny need to be more prevalent for a healthier culture. Or else we remain at the mercy of firms like GUDEA and their ilk, telling us which narratives to believe when they explicitly sell narrative control.