Storyliving by Disney: fan domestication on a grand scale

Past attempts to create corporate utopias may tell us more than we expect.

The announcement of Storyliving by Disney, the Walt Disney Corporation’s latest planned community is barely news if you consider earlier efforts of theirs such as Country Walk, Golden Oak, and Celebration, all in Florida.

What took me aback was the transparent fan appeal; not only do they tap into that emotional attachment, but they also claim the new communities will be a way for fans to “make Disney a bigger part of their lives.” As long as they have the funds, of course.

Disney’s wide appeal, innumerable properties and long history mean there is already a vibrant fandom community. But even the brand & resorts have fans of their own.

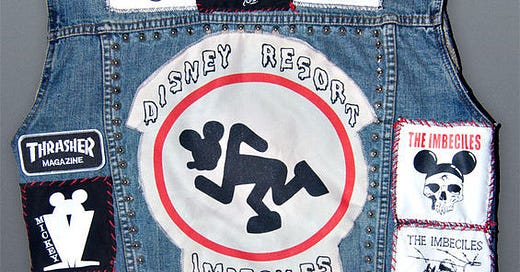

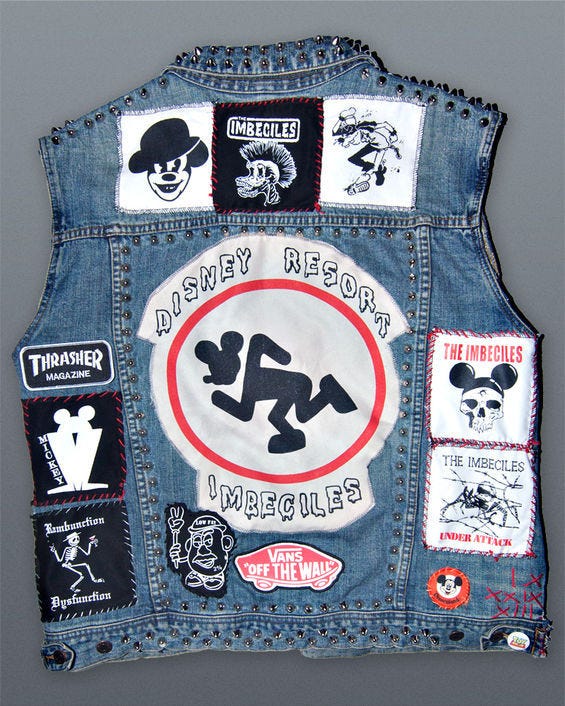

From the Club 33 members with its years-long waitlist and a yearly price tag of approximately ten thousand, to the Disney Social clubs on the ground. The clubs entered the scene about a decade ago and grew with thanks to Instagram. Easily identifiable by their jean vests and propensity to roam in large groups.

Where admittance into Club 33 seems a matter of status and economy, the social clubs are a free for all. Unauthorized, but welcomed by officials they manage their own gatekeeping and invitations. But should you not get into one club, you can start your own. The founder of The Hitchhiker’s Social Club made her own after being drawn to the existing scene. She said, “It wasn’t just a social club, it was a family club. These strangers had built a family foundation on their love for Disney and who wouldn’t want a piece of that?”

This foundation of love, the affinity for the Disney brand and products that can be experienced rather than absorbed and consumed, should be the foundation for Storyliving communities, too, shouldn’t it?

The branded fandom takeover of our lives, brought to you by corporate, was always going to show up. It was just around the corner, and Disney decided to deliver. They are far from the only corporate behemoth with the ambition to be there for every moment of their customers’ lives, and their children’s, and their grandchildren’s… it’s why I think it’s worth exploring.

The communal residential aspect is what stands out to me, but not because I’ve got a problem with shacking up with others based on your interests—I did, after all!—but that the promise of a community is premature. It depends on the people, after all, the dynamics and chemistry and a million other minute details that can derail relationships.

Such a promise might be difficult to deliver on, but as I mentioned, it isn’t Disney’s first rodeo.

“Disney’s only innovation, it might be argued, is that he bought enough land to make his the only voice in a tiny kingdom.” — Michael Harrington, To The Disney Station

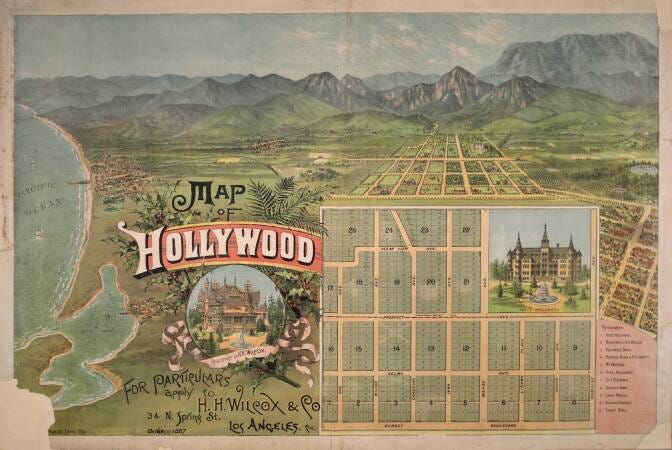

The vision of a constructed utopian society goes back all the way to Walt Disney, whose grand vision was E.P.C.O.T., an Experimental Prototype Community Of Tomorrow. It was what I would call a corporate utopia, according to Disney himself, “There would be no slums, and no unemployment, because people without jobs would not be allowed to live in Epcot. There also would be no home ownership, because everyone would rent from Disney’s company.” He’d even incorporated a dome over the centre, allowing for complete climate control.

To accomplish something so grand, the Walt Disney Company needed carte blanche. They lobbied the Florida government for concessions and worked on bills that favoured their needs. There was little to no resistance, and thus the Walt Disney Company was granted an Improved District, which allowed Disney to set up a sovereign government encompassing their landholding in Florida.

Disney runs its own utilities. It administers its own planning and zoning. It composes its own building codes and employs its own inspectors. It maintains its own fire department. It even has the authority to levy taxes.

Florida’s starstruck lawmakers didn’t stop there. They also gave Disney’s puppet government the authority to build its own international airport and even a nuclear power plant—neither of which the company has needed … yet. Reedy Creek is further empowered to have cemeteries, schools, a police department, and a criminal justice system—services that Disney has so far chosen not to assume.

— Carl Hiaasen, Team Rodent: How Disney Devours the World

“…yet” is he keyword in Hiaasen’s summation, as well as the fact that this happened at all should mean it might happen again, whether it be within the US or elsewhere, granting governmental powers to a corporation has a precedent.

Disney’s presentation on EPCOT was presented to industry by his successors, even though his plan was far too grandiose for them. They could, however, use his ideas as a springboard for extensions on the existing parks using the Epcot spirit.

Nearly thirty years passed before the residential part of the plan was set into motion: Celebration, Florida, the first Disney city. It was zoned out of the Improvement District, because otherwise the residents would be permitted to vote on Reedy Creek matters. Still, Disney ensured that the company retained veto rights on all homeowner’s association decisions. Most residents hadn’t noticed those provisions in their paperwork.

Despite their ultimate control, or perhaps because of it, there have been a few legal hiccups on their property. In 1992 six Magic Kingdom cast members claimed sexual harassment, invasion of privacy, and emotional distress when they weren’t informed that a voyeur had access to their changing rooms. Disney had permitted it to go on indefinitely, until they were ready to stop him. The excuse they presented? Cast members had no expectation of privacy in their capacity in their roles, so they could hardly claim damage.

In 1994 an 18-year-old was killed in a traffic accident involving Disney security personnel. A wrongful death suit followed, and with Florida’s open records laws and Disney’s official government, it seemed obvious that the court would receive access to archived security files. Disney refused to comply, arguing that as a private company they were not subject to the laws, and could not be compelled to share confidential information. They won.

One of the immediate concessions that had to be made was that Celebration shouldn’t be part of Reedy Creek; otherwise, the residents would be allowed votes and involvement on Disney matters. Of course, Disney still wanted to retain as much control as possible, so that was unacceptable. This meant that Celebration had to be zoned out of their district into the neighbouring Osceola County.

Prospective residents entered a lottery, and many of the costs were raised to accommodate demand. In other words, they could’ve had even more restrictive rules and regulations and still have a fully occupied community. AT&T offered the residents free internet, computers, and other tech as long as they were willing to have their activity recorded and reported on for a year’s time. All websites visited all phone calls, all emails. But this wasn’t an issue, “The willingness to swap some privacy for a free computer and phone was related to the willingness of people to move to a place where rules and regulations restricted personal freedom, too.” It’s an attitude we’ve seen plenty of times since, and likely will continue to thrive as the exchanges become more personalized and enticing.

Residents expected Disney’s personal touch and were heavily dependent on their involvement. Catherine Collins and Douglas Frantz documented their time in Celebration1 and noted as much. Many families seemed to be escaping existing problematic dynamics, the underlying expectation being that the Disney touch would massage their problems into B-plots with neat endings.

When Disney’s name disappeared from the water town signage overnight in 1997, it left residents distraught and anxious. Newsletters insisted that Disney wasn’t pulling out of the town. It wasn’t exactly a lie; it wasn’t until a few years later that Celebration was removed from Disney Resort maps.

It was a mixed blessing: shopkeepers expressed relief that their inventory, displays, and store hours wouldn’t be dictated by Disney anymore. Residents who’d been asked one too many times where Truman lived appreciated the decline in tourism. But the Disney touch that had drawn residents to the town was no longer even an illusion.

The attachment, in that case, may have been more towards Disney than the community itself, something that likely will be echoed in Storyliving communities. Some changes are the Disney programming and events, and of course, the presence of cast members as workers, delivering the Disney touch.

It doesn’t solve the problem that these spaces are nothing more than empty infrastructure and applied tourism theory until people move in and start to interact. But perhaps the offers of consistent, reliable Disney programming and events will be enough to keep people occupied and frenzied enough that they won’t have time to complain. We’ll see, I suppose.

“Celebration, USA: Living in Disney’s Brave New Town,” Catherine Collins, Douglas Franz, 2000

“Realityland : true-life adventures at Walt Disney World,” by David Koenig