The fandoming of everything is not just about the crowd, but also about the businesses that cater to these new audience categories to maximize loyalty. It’s gone far beyond traditional fan objects to any brand and company that wants to join the scene.

The industry term for this phenomenon and this modern era of marketing was dubbed the relationship renaissance by Chris Malone and Susan T. Fiske in their 2013 book The Human Brand. They argued that mass marketing needed to take a backseat and that “a new language of loyalty is needed,” for companies to succeed.

The book is a treatise on how emotional bonds and loyalty attachments can be fostered by catering to the drive for identification and internalization among customer bases. To start, companies and businesses need to present as more human (hence, human brands).

The primary reward for audiences in the relationship renaissance model is the relationship with the totemic brand itself, a result of successful brand identification and internalization. Devotion to the brand is expressed externally, via acts of customer evangelicism and consumer support.

The brand must become the totem around which loyalty is expressed, not the commodities it produces, and we are more likely to form attachments to what we humanize.

This loyalty attachment as described looks a lot like the fan ↔ fan object relationship that is the basis for fandom communities. In fandom, it is the fan object that is the totem around which groups organize.

The communal aspect is incredibly relevant to the fandoming of everything because it isn’t just about customer relations, but about developing “relationship management systems” (also known as standard fandom management).

One-on-one targeting isn’t enough because the audience isn’t static, it is made up of multiple sub-communities that organize among themselves and have their rituals and norms, and these communities themselves aren’t static either.

This has been recognized as a challenge in fandom management, as described by Nancy K. Baym in Playing to the Crowd: Musicians, Audiences, and the Intimate Work of Connection, where she deals with music fandoms specifically:

“To the extent audiences are markets, it makes sense for [brands] to approach them from positions of power with an eye toward control, asking how they can influence and manage audiences to maximize their revenue. To the extent audiences are communities, it’s not clear how to cede power and take a more participatory stance when you are the center around whom their participation revolves.”

Since fans will seek each other out to form social networks and communities it isn’t enough to target fans individually.

Fandom communities are not as profitable when their primary attachment is to each other rather than with the product. The loyalty has to be shifted to the brand or fan object: it must be totemized. This is the desired escalation from an ideal customer or mere fan to the preferred: advocates, evangelists, fanatical loyalists, and zealots.1

Mintel, which peddles in global consumer market analytics, declared the “relationship renaissance” as one of this year’s Global Consumer Trends. This marks a shift from advertising products to individuals into observing existing and potential social networks and stepping in and acting as facilitators and conduits.

According to Mintel, industries that should pay close attention to the trend are food and beverages, beauty and personal care, leisure, entertainment, fitness, and tech brands.

So how can brands shoehorn themselves into existing social networks and become central to their functioning? One of the approaches is for brands to create ecosystems where these communities can be managed and directed according to what is best for business rather than what is best for the communities themselves.

In the fandom space, the shining example is HYBE’s Weverse platform. Launched in 2019, Weverse is a closed platform touted as the place for fans to have a more intimate connection with their fan objects, but also with each other. '

In 2023, Weverse also launched the digital currency Jelly Coin, which fans can use to purchase direct messaging access and digital products.

Currently, it only hosts exclusives for K-pop fandoms, but considering Scooter Braun’s involvement with HYBE, American acts are sure to follow. Weverse’s president Joon Choi told Billboard recently that this is the year they “will aggressively work on raising the market awareness,” in America.

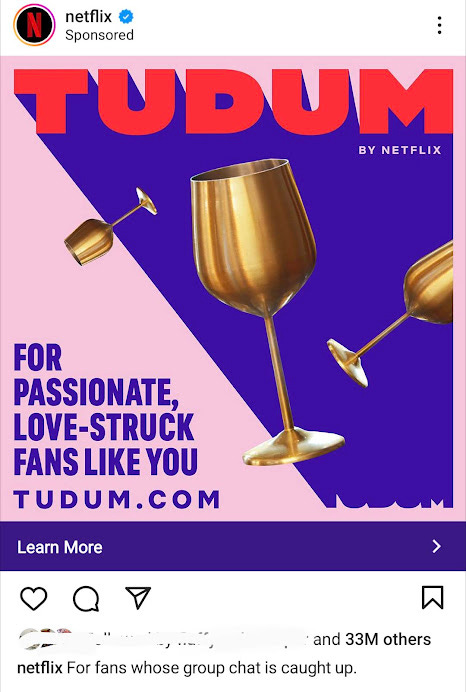

Netflix’s Tudum service tries to fill a similar role. Created “for fans to dive deeper into the stories they love, fuel their obsessions and start new conversations,” Netflix is trying to host the communities that historically develop organically on unrelated and unofficial platforms, detached from executive oversight.

The creation of heckler’s veto culture

A fundamental feature of this relationship renaissance is that brands need to be responsive to customers’ wants and desires. It’s good for businesses to adapt to shifting demands, but the reality is that what customers want isn’t always possible.

There’s little acknowledgment of how disruptive customer advocates (fans) can be when they feel slighted.

It’s easy to look at fandom spaces to see how these backlashes can take shape because of how empowered they feel. I’ve written about the myth of fan power and how fans have less of an impact than they believe, but that they believe they have a say in the first place is what drives much of the protests.

In the world of K-pop, a form of extreme opposition that has been normalized is “protest trucks” which have exploded in use since the pandemic, when in-person protests weren’t possible.

Some reasons for protest are incredibly petty, like demanding the firing of backup dancers or the removal of band members. But there are also many occasions when truck protests are used to blast the businesses behind the brands for mismanagement.

In these cases, fans are responding to what they perceive as attacks on their totems. There are protests against unpopular business moves, like BTS re-signing with HYBE, calling out the throttling of members or entire groups seemingly being held back, supporting members who are perceived as being mismanaged, breaches of privacy of their idols, or even failure to address malicious comments and anti-fans.

The last point stands out to me because HYBE regularly initiates legal action against users, as recently as December 2023, and they urge fans to report offenders to their legal affairs hotline. This precedent means that fans now expect action to be taken every time someone is reported.

Aside from trucks blasting them, in 2022, the fan group Purple Hearts initiated legal action and demanded that HYBE address online commenters targeting their fan object and indicted the Weverse platform for failing to protect. They also warned that “fans have the right to claim compensation for the mental and material pain and sufferings incurred to the artist and fans caused by the agency’s failure to perform its duties.”

This highlights just how far loyalty attachments can go. There exists an ownership of brand totems that comes with that type of loyalty, and defending something so important to you is a given. Considering there is no way to constantly meet demands, we should expect more such extremes from everywhere a market has coalesced into a fandom.

The audience isn't static, so their demands won't be either.

These are all terms used by executives seeking customer loyalty, not judgment calls on my behalf.

This stuff is constantly implied and/or rephrased in many music business advice resources for musicians; the idea of the "marketing funnel" from casual listener to "superfan" is a particularly popular emphasized concept.

I find it unsettling, as a musician of decades' experience; I know painfully well that the "bandwidth" of our culture has been shrunk considerably over 30 years by the Nostalgia Industrial Complex and the massive conglomerates that control the "pop" world; but the idea of demanding/soliciting so much energy from the smaller customer-base that remains with us seems unethical to me.

I like people. I like and respect their lives; which are different than mine. Trying to be the parasocial "center" of those lives seems to me disrespectful of their agency and integrity, somehow. I wish there were more room for my work and that of others like me to be just casual things that people enjoy, forgoing this needless intensity and fraughtness. We all have more than enough of that just trying to live.

Page 2

Aaron also attended the Danny Masterson trial everyday to give the Jane Does support and to support Claire who testified. Now they have 3 married couples on the board so Mike can have control over everything. Aaron raised 20,000 dollars from his followers for Mikes cancer treatment. Oh it’s embarrassing to raise money for Mikes cancer treatment. I donated as well and have no regrets. I cried when Mike was sick even though I did not know him. I also adored Clair and Marc. How I was fooled. But turning on Aaron and the other ex-Gens who I adore more than they know is egregious and unacceptable. It’s mind blowing to see that what they all have done to try to get rid of this cult and none of that mattered to Mike and HIS board. You do not treat your friends like that. I also have to say this Mike Marc and Claire had serious embarrassing allegations against them when they left the cult. Did that bother me? No because I believed the allegations weren’t true or they escaped and are doing the right thing now. Do you even know what Mikes ex wife and kids has said about him? Oh that wasn’t embarrassing? Maybe you do some research. I now believe Mikes ex wife and kids.