Considering the frequency of headlines praising fans and stans for their impact it may seem a strange time to put forth the argument that this impact is largely overrated.

An oft-cited proof of concept is the uptick in voter registration following Taylor Swift’s 2018 Instagram plea to keep Republican Marsha Blackburn out of the Senate.

Yet, Blackburn was still elected.

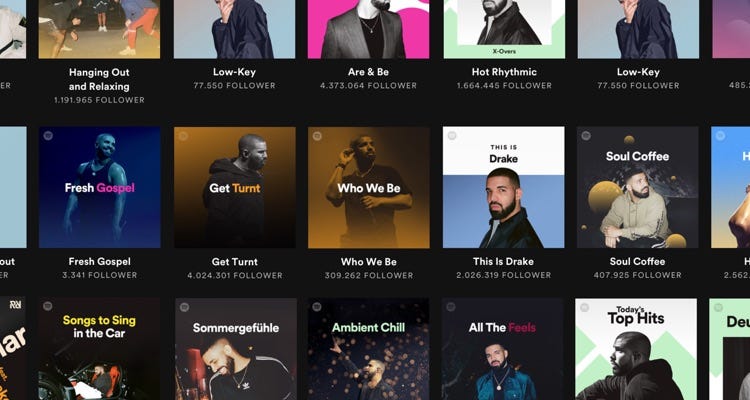

The rise of streamers has brought with it the illusion of more “natural” ways of discovering new artists and a more accurate reflection of what’s considered a Hit. But Spotify and other streamers have been working with labels to promote certain artists over others for a very long time.

Drake’s 2018 marketing campaign made a big splash on Spotify; he was everywhere, and people were not happy. It was still a massive success.

“In the end, whatever backlash Spotify saw from users made little-to-no difference in the massive ‘Scorpion’ streaming numbers, nor did criticism of the album's middling artistic content. That's good news for Spotify, great news for Drake, and depressing news for music fans.” —Maeve McDermott, USA Today

Spotify’s Daniel Ek has been pushing marketing collaborations for some time, claiming it’s a great tool for any “up-and-coming indie artist” — but the indie artists are not the ones with big budgets behind them. What the Drake takeover illustrates is the reality that “streaming services adopt editorial slants to benefit the highest bidders.”

Whatever problems indies had—and still have— with radio is the same problem with streamers. Indies are not the ones with playlist pitchers making sure they are in the first 10 tracks of “Today’s Top Hits,” the playlist that creates hits rather than rounds them up.

It’s one thing to be aware that the ecosystem is rigged; it’s another to experience it firsthand. My disillusionment came with One Direction’s solo efforts, particularly that of Louis Tomlinson.

As a band that built their fanbase off social media, a band where each member had massive fanbases it felt like a shoe-in for all members to be afforded industry support. Five thriving performers is a boon to the industry at large, isn’t it?

Things started off promisingly enough with a flood of solo-1D feeding the fandom, resulting in all five ex-members charting in the US Top 40. Reported on by Billboard in August 2017, they specified what a feat this was, saying, “One Direction joins only the Eagles and Fleetwood Mac in containing, at one time in their respective histories, five members with individual top 40 hits on the Hot 100.”

There were already massive discrepancies in public presence, marketing opportunities, and industry backing, but this suggested that there were audiences there, waiting and willing to absorb new content.

This was possibly the last time that there was any impact from fan bases, because there wasn’t actually any interest in creating 5 thriving careers.

To celebrate this full pot would be a loss to Sony, who let Niall Horan and Liam Payne sign with UMG, and who had no interest in pumping money into “the other two” they kept on.

Sony Music’s Rob Stringer had bet big on Harry Styles, allegedly signing him for $90 million, he hand-delivered a Grammy-winning producer tasked with delivering Jack White lite, in a Grammy-friendly package.1

This might seem like the reverse of what I’m talking about; how can fans have no impact if it shows that the expected Styles clean-sweep didn’t happen? Despite the massive publicity spend and near-ubiquitous public presence?

Fans can make waves—but it’s the industry’s job to pick up on that momentum and build on it. K-pop fans are some of the most proud of their accomplishments, yet even they are at the mercy of the industry. SM Entertainment calls itself “the leading entertainment group in Korea” and they were found guilty by the Korean Fair Trade Commission of blocking artists from exposure.

In his exploration of music diffusion, Climbing the Charts, Gabriel Rossman refers to the Hirsh Gatekeeping Model to understand this funneling of stardom, and defines the mysterious middlemen as such,

Cultural distributors are firms like record labels and book publishers that provide artists with the financing, technical collaborators, retail distribution networks, and other resources to produce their art and get it to market. Surrogate consumers are such actors as radio stations and book reviewers who do not produce art but draw attention to it.

None of these things can be accomplished by fans.

What fans try to do is reverse engineer the model; show the demand and passion and hopefully, logically, the labels and surrogate consumers should catch on that there is profit to be made. But what if they don’t? What if pre-orders are canceled, songs aren’t serviced to radio, and certifications aren’t applied for, what if world records aren’t even reported on?

As

pointed out, “actual blacklisting looks like this: quasi official strong-arming behind the scenes and the label simply NOT SENDING numbers to the chart company.”Why would they leave money on the table? Motive can only be speculated, but (in)action and ineptitude have been documented, and that can’t be ignored. In Tomlinson’s case, it’s undeniable that some sort of block was in place.

One of the most basic activities fans can partake in to gain exposure is to request songs from the radio. But what happens when the stations don’t have the songs? What happens when they apparently aren’t supposed to play them, even when the artist in question was a guest?

Exactly that happened with Atlanta DJ Ethan Cole, who hosted Tomlinson for an interview, yet apparently was under instruction not to play his music:

An even bigger setback was when radio requests were heard and fans were told that they didn’t have access to the song. I discovered JC Chasez fans faced the same hurdles in the early aughts. Old forum posts talk about fans requesting his singles only to be told the radio stations “didn’t have access” which just means the label never distributed the singles to them.

In 2021, an organized fan project launched the song Defenceless to the top of the worldwide iTunes chart and landed in the UK top 40. At the very least, this meant it would receive a play on the Official Top 40 countdown.

That’s what it got: a singular spin.

The next big fandom effort came with Tomlinson’s sophomore album. The midweek numbers placed him in the lead ahead of Bruce Springsteen, which was promising. But for some reason, this led to all the UK media throwing their weight behind Springsteen and his album of cover songs.

The BBC’s focus on Springsteen was bizarre when you consider this American legacy act was facing off with a homegrown Englishman, but it wasn’t surprising.2

Lisa Wilkinson, BMG’s director of UK marketing, shared some “behind the campaign” details and mentioned that BBC “shut them out” from the air. Wilkinson gave more credit to radio than fans, saying it made sense that radio wouldn’t want to play three former bandmates at the same time. That’s a hard sell for those of us who were around in 2017, the year that they all did so well.

The why behind the BBC Radio 1 block on Tomlinson remains up for speculation. Aled Haydn Jones, head of the station and former head of programmes, has been very proud about their role in the industry, telling Music Week, “We’ve been really powering the music industry and had lots of new talent coming through.”

In addition to this new talent, Haydn Jones also claimed responsibility for breaking Styles, saying, “[BBC Radio 1] was central in the roll out,” and pointed out that BBC’s relationship with Styles (and by default, Sony) stretched back a decade. They were certainly a massive part of his original launch, with multiple specials and live lounges, multiple A-list placements, and most notably: a TV programme intended to “celebrate one year solo” that was filmed three months into his career. (Math is hard, I guess.)

Whether this commitment to Styles and Sony is part of the reason why Tomlinson was left in the dark remains a question mark. What is certain is that fans cannot compete with those types of middlemen.

Fans can sustain careers if they start from the right place and if the fandom infrastructure is strong enough, but they can’t add exposure. They can’t do the work of the still-important middlemen.

When you see articles about fans’ instrumental role in launching artists to stardom, remember: it’s written for the fans. When you believe you’re having an actual impact you’re more likely to stick around. And the reverse—when you realize you have little to no impact, the disaffection is profound, and attrition is inevitable.

I remain convinced that the only reason HS1 was left off the Grammy plate was because it was submitted as rock. There was no slipping him in under that guise.

More details on the Springsteen vs. Tomlinson chart battle covered in The Big Business of San culture post.

If you get the chance, check out the documentary “The Ramones: End of the Century,” which shows how hard this game was working in the 1970s and 1980s. Every attempt the Ramones made to get airplay, including hiring Phil Spector to produce the album “End of the Century,” was instantly neutralized by the label. In the early days of MTV, Ramones videos, particularly for the songs “I Wanna Be Sedated” and “We Want the Airwaves,” played constantly, but people going to most record shops to buy them were simply told “they should be available in two weeks” until they caught on that the shops would NEVER carry Ramones albums, no matter what. Even today, you’re more likely to hear Ramones songs as ad jingles, especially after all of the original band members died in the 2000s, than you are to hear them on terrestrial radio in the States or England, and while labels will make the songs available NOW, all of the band members pretty much died in poverty, for no other reason than a group of Rolling Stone alums figured that Phil Collins and Stone TemplePilots could move more units.

I tend to think that executives "blacklist" artists as a display of power; particularly to thwart corporate-political rivals or punish agents that have irked them. It's only very rarely about the artists themselves.