I picked up Kelefa Sanneh’s highly recommended 2021 tome, “Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres” and found myself stumped in the introduction by the following passage:

I wrote about music that was excellent or popular or interesting, in that order of importance, with a special focus on musicians who satisfied at least two of those criteria, and extra scrutiny aimed at musicians who fulfilled only the last and least one. (Too much music coverage, I think, is devoted to music that is supposed to be interesting, despite arousing no particular passion in either the general public or the person doing the story. If it’s not popular and it’s not excellent, are we sure it is nonetheless interesting?)

This is the exact opposite of how I feel about what I want to read and write about when it comes to culture, especially music. Being interesting, or inspiring interesting thoughts and perspectives, is truly my first priority as a reader and writer.

Of course, Sanneh is writing about his own approach to criticism and that which is clearly valued by the mainstream, big name publications. It worked for him, and it certainly has proliferated in today’s digital terrain, but it’s also exactly what has turned me off of most music writing.

I didn’t realize that Sanneh was the author of the seminal “poptimism” piece of 2004 until Freddie deBoer took it on, contextualizing what came to pass in the two decades since its publication. It certainly makes sense that Sanneh would care more about what’s popular than what’s interesting, knowing this is where he was coming from.

Despite having been a rabid fan since before Sanneh was working in the mainstream, I had no idea about this approach because I was too busy being a fan in fan spaces, with no concern with what Pitchfork, Rolling Stone or The Times had to say about the albums I had on rotation. Plenty of them were skewered then, some reconsidered since, some doubled down on, and yet, that has nothing to do with my enjoyment of the music itself.

Excellence I understand—technical proficiency is nice, but it’s also sterile. It can be learned and (hopefully) acquired and honed over time. If we’re talking about perceived quality, the statement of something being “good” or “bad” outright (because remember, whether it’s interesting doesn’t matter in this scenario) then that’s subjective enough to be meaningless.

Popularity waxes and wanes, often at the whim of factors far beyond the creators’ sphere of influence, those factors interesting in their own right, which is where it becomes relevant to talk about popular things. Oftentimes, the audience reaction and discourse is what’s interesting, not the product itself. Inevitably, everything becomes paratext rather than about the creative output itself. It’s aggrandizing in a detached way, serving the hype machine.

Context is king, in my opinion. There are plenty of popular excellent things that I don’t care about in the slightest, but a piece of writing on it can still be food for thought if it manages to address something new, approach from a new angle, or elucidate something that reframes the picture.

There’s no room for context, history and perspective when you’re hype surfing. Being in the middle of the popularity tornado means missing so many things that will only be clearer after the smoke clears. I personally think that hype kills appreciation. I enjoyed Oz Perkins’ Longlegs, and I’ve seen a lot of people complain that it was overhyped, meanwhile, I was spared and engaged in minimal hype around it. If I had been pummelled with it, I might also have been disappointed. Conversely, Challengers was a massive letdown because of the hype and false advertisement that was unavoidable in my sphere. Without, the film might have stood on its own merits.

Whether something is interesting is also personal and subjective, but at least it’s something where a case can be made. It requires more effort to explain what's interesting rather than simply stating that what is good is popular, and what is popular is good, end of story. There is no end to the story when you have to verbalize your perception and make it legible to others.

This focus on the popular is also a foundational issue with stan culture: because stans deal with industry metrics, they are blinded by “popularity” metrics such as revenue, streams, units sold, accumulated five-star reviews and coverage, the Hits Daily Double HitsList, etc. It depletes fan bases all the more when the mainstream edges them out, and they are no longer popular enough to warrant the fawning coverage that feeds the beasts. The winner take all world hollows out cultural appreciation, and that the fire being stoked.

These metrics serve as a cudgel in stan culture: no longer are fans angry about their fan objects selling out, instead, having “outsold” someone is a victory cry wielded by the most bloodthirsty true believers. Good things can be popular, they can be interesting, and they can be excellent. But popularity in itself will never be a metric I take seriously on its face.

Which reminds me of the common insult outside stan circles that someone/something isn’t “relevant” anymore. In the most lenient readings, it can simply be seen as someone saying that the topic at hand isn’t relevant to them personally, but isn’t everything irrelevant until it becomes relevant? Isn’t that the beauty of discovering new interests? On a basic level, most people know this is how the world of culture works: you’re not interested until you are. I didn’t care about coverage of The Beaches until I started listening to them: they were irrelevant to me before, and now they aren’t.

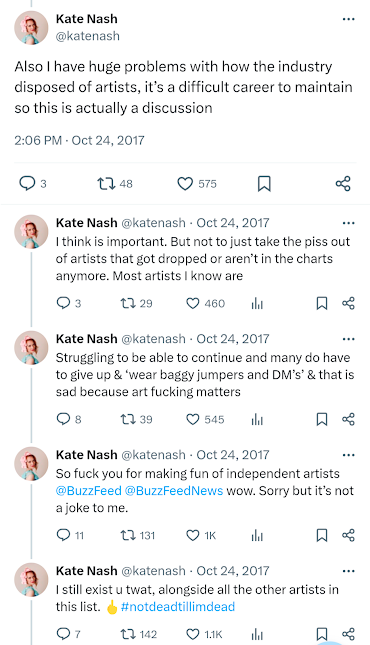

The claim that something isn’t relevant is more a way of saying that it should “stop taking space” and “stop trying” to do whatever it is they do. They’ve been voted off the cultural island and should stand in the corner of shame. It makes me think of a Kate Nash Twitter thread from 2017, wherein she responded to a Buzzfeed listicle that listed her as a forgotten artifact that only exists in millennials’ memories.

I liked Nash when she was being peddled by her label for her debut, she did the rounds on local media and I gobbled it up. I also “forgot” about her because she wasn’t being pushed into my face anymore after that, and the carousel of content continued spinning. It’s only after discovering her response to that article that I realized there was a backstory to why she wasn’t being planted in everyone’s face anymore.1

One thing I keep telling people is that doing music industry research has made me realize how many of the beloved artists of my youth went away not because they found something better to do, but because their support structures either vanished or turned against them. The System so often works against creatives and the difficulty of getting out there and working through the labyrinthine landscape unless you’ve got substantial backing and support. And I don’t mean fan support.

(I’ve addressed the myth of fan power previously, which is so often referred to as a lifebuoy for artists who have run afoul of the biz. There is only so much fans can do, and the overselling of our Power is one of my biggest gripes. Which is probably also why popularity as a metric bothers me. Do you actually know what is popular, or just what you’ve been told is?)

No one deserves to be in the public eye, you might say, and that’s why the talk about industry plants has heated up considerably as the cultural landscape has flattened. This becomes an even bigger problem when being in the public eye is seen as the reason to continue the cycle—this idea that popular things are popular because they deserve to be, because their supremacy is inevitable. It’s ahistorical and, above all, beyond boring.

I’ll return to Sanneh’s book at some point, as I’m sure there’s plenty of good information in it, regardless of his approach to his own role as a critic. It is about history, after all. But I find it galling that these priorities are stated outright. Sanneh says that manipulation of popularity/statistics never really lasts, but that’s beside the point, because you don’t learn about the manipulation until long after the fact. And by default, if you’re stuck in the spin cycle, in the perpetual present of the hype du jour, you’ll never have to face it. You're always right because you're always surfing the hype, never looking back unless it's to sneer.

Because popularity is cyclical it is usually the least interesting part of any piece of media. How it got there, the mechanics behind boosting and maintenance and scaffolding that is required to run the business of a popular brand, that’s interesting. To me, at least.

I recommend checking out her documentary “Underestimate the Girl” which delves into being dropped after her #1 album, being scammed by her manager, and the court battle that followed. It explores the working musician’s daily efforts.

I've been thinking for a while about how to phrase this... First up, I really like your blog! And secondly, I would be really interested to know your thoughts on the modernist ideal, that generalised idea among artists in the, let's say, 1920s through to the 1960s (ish) that high-art concepts could actually be transmitted to the masses through a combination of both high art and mass media. I think that stuff like TV, music, and fiction was seen as the tool of societal transformation throughout that entire period, and taken really seriously – in other words, that art which was interesting and excellent was *also* assumed to be popular. There was no differentiation. "Difficult" art was to be transmitted to the masses. In Europe and the USA at that point, there was serious government funding for the arts because they were seen as "bettering" somehow; it was a public service. So, say, Picasso, or Joyce/Woolf/Beckett, or composers like Shostakovich – they all trusted the public to keep up with very academic ideas that were interwoven in their art, which (to me) is something that the arts have abandoned.

So art now is either popular (the MCU, stan culture, whatever), or "good" (Oscar winners that no one sees, winners of stuffy art prizes or, say, world cinema which shows in thirty art-house cinemas across the nation). But not both at once. Right? Or – do you think there are serious, respected and successful artists in any medium who combine those difficult and groundbreaking ideas with art that is genuinely consumed on a mass scale?

I love this piece (and all the posts on your blog as of late) but I must belatedly-yet-strenuously object to one tangential thing here: Live it Out? A 10/10 no skips album? For real? "Poster of a Girl" is a bop but the median track on the record is sludgy unstructured punk crud where Emily Haines sings lyrics off a marginally clever bumper sticker. ("I fought the war and the war won" - ha! ha! Etc.)

I'm maybe being too harsh here because IMO Old World Underground... *is* a perfect album! Sooo good. I think part of the brilliance here - and I might be talking out my ass here - is that the album is both of its era but also broadly contemptuous of that era and the way so many post-9/11 indie bands were larping past countercultures. "All we get is dead disco." Etc. I've listened to both of these records a gazillion times since they came out and have strong opinions about them. But only those two, not their later stuff. Apparently Metric have put out SIX records since the Scott Pilgrim movie came out?? Jeez!!