“A loyal audience can begin to feel like a prison.” — Rick Rubin

I’ve questioned the utility of fan campaigns in the past, but I’ve been thinking about it a lot more lately.

Much of my research has suggested that most successful campaigns are typically backed by industry players, something I’ve covered before, but that doesn’t stop people from trying.

And sometimes fans do move the needle, or at least accomplish their short-term goals. I’ve discussed my own involvement in One Direction and solo-Direction campaigns, where the ultimate result was beyond disappointing despite the immediate appearance of success, because there’s only so much external audiences can accomplish.

Idolcast has discussed the Belle & Sebastian 1999 Brit Award win, rallied for by fans. What was seen as a gift to the band, a launching pad brought to you by sheer devotion, became more of a burden weighing them down.

That’s what interests me. This idea that even if a fan campaign succeeds on paper, it might ultimately harm the fan objects themselves, from actors who are done with a project and tired writers, to the decline of a once beloved media property because the spark just isn’t there anymore.

One of my early fandoms was The WB’s Roswell, and as a show that was on the verge of cancellation from the start, it was the subject of multiple fan campaigns fighting for its renewal. By all accounts, fans succeeded twice, getting the show renewed for a second season on The WB, and (presumably) convincing UPN to pick up the show for a third season.

I didn’t participate in any of these campaigns, but I observed them from overseas, cheering on my fellow fans in their dedication to sending Tabasco bottles to the network. According to The New York Times, 6,000 bottles of Tabasco were sent to The WB over a three-month period the first time the show was on the bubble.

When the troops rallied again the next year it was clear The WB was done, and instead the target was UPN. This time, 12,000 bottles were sent to their offices over three weeks.

Dean Valentine, chief executive at UPN at the time, said this effort “made a difference,” but I personally wonder how much of it was a profitable package deal with Buffy the Vampire Slayer, which moved to UPN from The WB in the same sweep. He also mentioned that the viewer profiles for both shows were “almost identical.”

In a 2009 interview with The Television Academy, Valentine expanded on the strategy, which was entirely financial,

“The strategy of finding stuff that was already made for pre-existing franchises that we could justify on a P&L basis. [...] When you looked at it on a pure cash in cash out basis, we would make money just from the advertising and the lift to shows around Buffy on schedule, so I could justify it and it wasn't like spending money, it was like buying a bond.”

This is a case of a successful campaign that maybe shouldn’t have worked. Not only did the show barely last one season on the network, it seemed there was a sense of fatigue among the cast already, exemplified by Brendan Fehr’s story of pissing himself on set for a dare. You don’t do that on a job you treasure.

Many corners of fandom were also already disillusioned, a longstanding fan community had even run a campaign of their own, declaring that the show should be “euthanized” so we could all be put out of our misery.

Despite fan efforts being credited and fan empowerment being a big buzz word, only two campaigns were successful. And there were many, many more campaigns. A compilation on Roswell Oracle reveals that there were at least 54 campaigns over the years. From efforts in its heyday to get the cast on magazine covers to post cancellation attempts for a film.

Not all corners of fandom were united on what they wanted. This is clear already from the euthanasia campaign, but also common sense. There were campaigns to have Emilie de Ravin’s character written off the show, and once she left, there were campaigns to get her back.

With the news of the UPN pickup came a fan created “wish list” that was decidedly ignored. Because although fans wanted more of the show, the majority wanted more of the show they loved in the first season, not what it had become later on.

Ultimately, season 3 was incredibly different from the earlier seasons, and the series fell out of favour with the fans. There was a renewal campaign but even if there were interested buyers, the reality is that the fan base had diminished drastically over its last season.

There’s the crux of it: the fans are not, ultimately, in charge. They are the proverbial observers, affecting outcomes by their mere presence, but they don’t have a say, and they can’t. As Jason Katims, executive producer of the show, told NYT, “If you tried to service all [the fans], it would be harder than trying to please a network.”

Another notable fan campaign was the effort to save the Buffy spin-off Angel, which was cancelled in its fifth season.

This was an elaborate, involved, and long-running campaign: there were billboard trucks, rallies, postcard campaigns as well as full-page print ads taken out in industry press. But without the talent willing to continue, was there any point in all this effort?

David Boreanaz, the titular lead, told BBC, “I'm not planning on any kind of reunion with the character unless it's done in a very challenging and big screen way.”

This made fans regroup and redirect their efforts into getting a feature film produced. With the success of Firefly coming to the big screen, it felt like a possibility. Ultimately, this didn’t happen, but the rallying carried on for quite a while.

Firefly’s jump to the big screen was also far from smooth. I’ve covered it before, but this fandom is relevant in this context as well. Despite the strife with Universal Studios, fans hadn’t been turned off the property.

In 2011, nearly a decade after the show’s single season aired, and five years after the feature film came out, lead actor Nathan Fillion made a comment that mobilized fans, “If I got $300 million from the California Lottery, the first thing I would do is buy the rights to Firefly, make it own my own, and distribute it on the Internet.”

A group of fans ran with it and tried to raise money for the cause. This project didn’t get very far, not because there weren’t pledges—there were many—but because it didn’t take long before a Whedonverse writer and sister-in-law of Joss Whedon took to Twitter to say this campaign wasn’t welcome.

The campaign was shelved soon after.

I personally am not sure I get the logic of raising money to allow someone else to buy the rights to a property; how do you know they’ll do what you want with it? The promise of more is no guarantee that it will be what you want, Roswell shows that well.

These are far from the only tales of questionable fan campaigns.

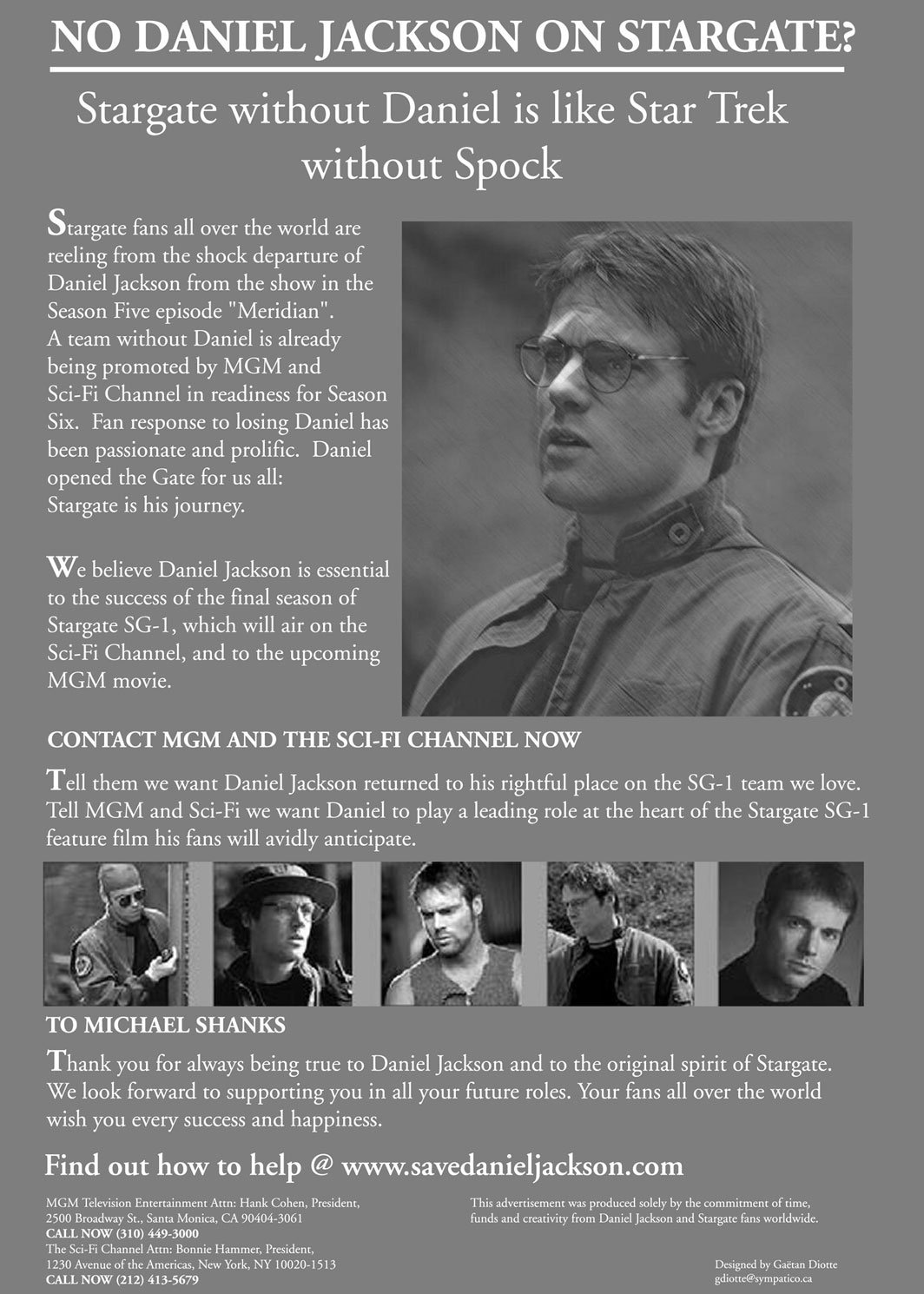

Henry Jenkins covered the Stargate SG-1 fans who tried to revive the show when it was cancelled in its 10th season. One of the key takeaways from the excellent post is,

There's a tendency for both academics and journalists to compartmentalize fandoms rather than seeing fandom as an interconnected network. Fans move between series and as they do so, knowledge gets transmitted from one fan community to another.

The Stargate SG-1 fans had previously successfully rallied in bringing back a character who was written off, but in this case, the actor wanted to return. They were boosting his interest, not just their own.

Now they were acting in self-interest, but framed it as a concern that extended beyond that.

Cancelling the show wasn’t just bad for the show and its fans, it was a death sentence for the network itself. The Save Stargate SG-1 site proclaimed, “Now is the time to tell them to save not just Stargate SG-1, but themselves.”

In the years since, fan campaigns have gotten all the more savvy and industry aware, but whether this has borne out with satisfactory results is questionable. Fans have been told they hold the power, but I doubt it.

But I’d love your input if you have any. Have you participated in any fan campaigns and did they succeed? And if they did, were you happy with the outcome?

Very recent:

The campaign to get Loona's label to release them from their abusive contracts, by boycotting (and therefore denying the label money) until the label agreed to reasonable terms with the members, succeeded.

I think that followed classic boycott dynamics: if you can prove to a company that you control their supply of dollars, and they can get it back by agreeing to reasonable demands ("stop being abusive in contract negotiations"), they will often back down.

Older:

Very famously, Star Trek (the original series) got a third season due to fan campaigning. And Star Trek: The Motion Picture got produced because Roddenberry pointed to the existence of the fandom as proof of marketability.

Gates McFadden was removed from ST:TNG for season 2 by the preference of Roddenberry, and reinstated for season 3 due to very clear opinions by fans who wanted her back.

So, sometimes execs listen to fans, which, well, aren't all businesspeople supposed to listen to their customers? "The customer is always right in matters of taste", right? It's actually an aberration to do something else.

When the fandom represents the majority customer opinion, and the fandom has a majority opinion, going against it is a "we don't want money" choice, which you would not expect a profit-oriented producer to make.

Obviously some fan campaigns demand too much in too much detail, or demand the impossible, and the producers promptly disregard that. Some fan campaigns are dismissed as unrepresentative of the general market.

But the Star Trek producers knew that their fandom did represent their market, and knew how to tell whether they were looking at general fan opinion vs. a minority view. So of course they made the more marketable choice and brought McFadden back, right?

Sometime in between those dates:

I've actually been present for a group preparing a spinoff from Doctor Who (K-9) who were market-testing their ideas at fan conventions. They weren't sure how their concepts would go over with Doctor Who fans, who they wanted to attract. Literally everyone said "Are you hiring John Leeson?!?". NOBODY wanted any other voice actor for the robot dog! They had not been planning to do so. I watched the producers leaving the convention looking at each other saying "I guess we have to hire John Leeson!" Leeson later thanked the fans for giving him continuous work in his late career by repeatedly insisting to producers that he was the One True Voice of K-9 (even though there *was a second voice actor* for K-9 in the original series)!

So if the fandom (a) acts in a unified fashion and (b) demands something clear and simple and straightforward to do, producers will typically go along. Because they live in the same economy as we do. They want the fan dollar. If the fan demand is unified simple, clear, and easy to implement, it would be *odd* to not go along.

It's only if appeasing the fans becomes more complicated than "hire John Leeson" or "bring back Gates McFadden" that they go "not worth appeasing the fans".

Well—there was the Young Justice revival. I actually did a giant writeup about the fan-effect on an earlier blog, which I'll DM to you if you're interested.

But here's the short version.

In like 2010 the guy who created the cartoon Gargoyles in the 1990s launch a DC superhero show on Cartoon Network. It was surprisingly good, and it massed a cult following. After Season 2 it was summarily cancelled to much wailing and gnashing of teeth. There were all the usual online petitions, &c, but to no effect.

The thing about the creator (Weisman) is that he was kind of ahead of the curve in engaging with fans of his show online. There was a website where he'd post his answers to fans' questions about Gargoyles in the mid-1990s, and apparently he answered MOST of them. He's really engaged with and receptive to his core fanbase.

I don't know/can't recall too many of the details about the fan campaign(s) or how much of a role it/they played in WB/HBO/whoever they are now's decision to relaunch the show on DC's short-lived streaming service, but Weisman has more than once credited the revival to YJ's passionate cult following.

For a number of reasons, the revival--well, it wasn't very good. But one glaring new issue was that early 2010s YJ was made for a general audience on a basic cable channel, whereas late 2010s-early 2020s YJ was made for the superfans. Before it was cancelled again, the last season practically had Young Justice Twitter in the writers' room. By that point I had aged WAY out of the thing (in spite of the awkward attempt at rebranding it from a TV-Y7 to a TV-14 affair) and was watching it just to gawk at how *weird* it had made itself.