Film Industry Realism

Working in and around the business of film was disillusioning to the core.

Film is my first love. The industry that produces and distributes it, however, I don’t love so much. It might be an obvious sentiment, but I’ve come to it from experience.

Over the past twenty years, I have volunteered, worked and interned at multiple film festivals in Europe and North America. The current tally stands at 6 separate fests. Each role had varying degrees of responsibility and longevity—the longest gig I had recurred over a decade, so I do think I have put in enough time to have formed some opinions.

I’ve also worked on truly independent film projects that were submitted to festivals, and did a stint in film distribution with a focus on film festival submissions, seeing the other side of the festival carousel.

For a long time my dream gig was festival programmer, and it took quite some time before I was disillusioned enough to realize that it is far from what it is cracked up to be, and that the festivals themselves weren’t bastions of integrity, aiming to share art with the people. And in some cases, the same handful of programmers ruled over the local festival scene.

My first year of proper work for a festival was in close co-operation with the guest department, and by default the programming team. It was then I learned that some films would only be scheduled if the actors and director could attend the festival. Without the star power, these films were not of interest.

That is to say, this wasn’t about bringing art to the people. It might have been a pleasant side effect, but it wasn’t the raison d’être that I had ascribed to the fest— my bad, ultimately.

This wasn’t unique to that particular festival, either. The recent SAG-AFTRA strike caused many European festivals to panic about the lack of star power they could pull.

Yet, there wasn’t a total absence of names in attendance, because not all producers were being targeted by the strike. The red carpets rolled on, and when Adam Driver attended the Venice Film Festival in support of Ferrari, he commented that he was, “very proud to be here to be a visual representation of a movie that’s not part of the AMPTP.”

In my early festival days, I didn’t realize that many of the prestige festivals were either not open to the public or cost-prohibitive to the public, which leads to a very insular crowd that attends. As Scott Phillips pointed out in Forbes, “Sundance is attended by film fans who can spend thousands of dollars for a week of movies in a resort town in Utah.”

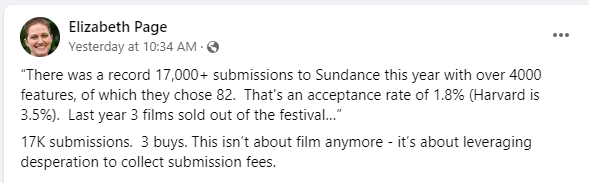

If we’re talking about exclusivity, there’s also the reality that the acceptance rate is incredibly low. It’s one thing to know that the odds of having your film programmed are bad, it’s another to see the numbers.

This year’s edition of Sundance received some coverage over its impressive submission rate, marking a record 4,410 feature film submissions.

As the above screenshot points out, this means the acceptance rate for a feature film is 1.8%, which is actually pretty good compared to Sundance’s foil, Slamdance. In 2020, they boasted 8,231 submissions, and since they only scheduled 11, the acceptance rate there is 0.13%.

In a recent post on the state of indie film,

said, “Your disaster is both a revenue stream for them and a justification for their being,” which is what these stats remind me of.There’s also the reality that submission fees aren’t asked of everyone.

Many of the festivals waive the fees for the very people who can afford them. I learned this when I worked in distribution. Sundance was one of the festivals that waived the submission fees for us. We didn’t get accepted, but at least we didn’t waste $65 to $110 per film. Maybe that seems like a low fee for such a prestige festival, but multiply that by the amount of submissions you’ll have to do to get programmed anywhere. Because it’s about odds, right?

The costs add up quickly.

Not only are fees waived for those with connections, but plenty of films and filmmakers are targeted individually; either invited to submit or to directly invited to screen. The process for TIFF has been documented publicly, so you don’t have to take my word for it,

“Piers Handling still remembers the taste of the wine — Francis Ford Coppola’s wine, that is.

The director and CEO of the Toronto International Film Festival sipped the delicious red while visiting the Oscar−winning director at his California winery to see his film "Twixt" in his cutting room.

He was there with Cameron Bailey, artistic director of TIFF, to decide whether the film should be a part of the 2011 festival. It ended up in the lineup.”

— A behind-the-scenes look at how programmers select the films for TIFF, 2017

Although TIFF is open to the public, and they like to proclaim themselves “the people’s festival,” that doesn’t mean that the cost isn’t somewhat prohibitive for us plebes. But the glitz and glamour of red carpet premieres attract audiences,1 even if the movies themselves are sub-par, even if their Cineplex premiere is less than a week out.

It’s pretty obvious that the festival has been pivoting more towards industry over the past decade. In 2014, seemingly as a response to the increasing status of the Telluride Film Festival which takes place just before them, they stated that premiere status would influence if and when films would be screened. That is to say, they wanted studios to pick between the two fests, indirectly punishing those that chose to premiere before Toronto. And recently, they announced the creation of an industry market that aims to double industry attendance.

Perhaps this will be a positive for the industry at large, but it’s not benefiting the people. The claim that their People’s Choice winner is a weather vane for the Academy Awards is more about status positioning than anything else.

Even before this, I was lucky enough to attend a few TIFF press and industry screenings, and was shocked to discover that these screenings were more disruptive than public ones. A lot of the attendees didn’t watch the whole movies. Either they’d leave after twenty minutes or come in halfway through.

These screenings were buffets to be sampled rather than films to absorb.

Since it’s Cannes season, I’ve been thinking about this a lot. My film focused newsfeeds are littered with headlines about epic standing ovations and red carpet glamour shots. I still love film and think festivals are one of the few ways to access film you would never see otherwise—but it is increasingly harder to navigate. For each blockbuster contender that Cannes platforms, something is left off the table.

It’s a reminder to me that business has become more and more about insular hype than anything. The hype is part of the fun for some, but for me, it’s the sign of the greater context collapse of culture at large. Festivals have a very particular audience, and the atmosphere is unique and ephemeral.

The magic is in the moment, not in the game of telephone that follows. As IndieWire’s Eric Kohn says of the ovation reporting trend,

“There’s a more practical reason for the surge of ovation reports: They reflect ways that media and European film festivals are each evolving to meet the demands of a 21st-century news cycle.”

For the longest time I referred to this post as my ‘film industry black pill post’ but it doesn’t sit right with me anymore. Because I do still love film festivals— they just need to be looked at with more skepticism and less starry eyes. Not to buy into the PR lines so much, and recognize that we need to steer our own ship instead of settling for the prix fixe options.

One of the greatest ironies is surely that the most prestigious premiere venue, Roy Thompson Hall, doesn’t allow the audience to even witness the red carpet. So what exactly are you paying a premium for?

I appreciate the honesty. As a person also working in and disillusioned by film, this hits home. I wonder if regular people even still care much for movies, or if the audiences for different mediums are branching off. TikTokkers to TikTok. Film snobs to film. TV bingers to the couch. Lots to think about. Great post!

I really appreciate the numbers you write, Monia, not only for the topics in sections, but also for how you talk about them. The topic of the film industry is one of those that has always attracted the most attention. And not only from an economic point of view, but also from the psychological relationship that people have with cinema characters and films - and TV series. One of the most intriguing studies I read on this showed for example that when a campaign features a testimonial who has had a famous role as a character from a TV series (for example Barney in How I Met Your Mother) presenting him as a character and not as an actor with his real name, in case of a scandal in which the actor is involved the negative effect on the advertised brand is less. I think it's just one example - very interesting in my opinion! - how much this industry deserves attention under a multidisciplinary lens and made up of many experiences like those you highlighted.