Introducing Forensic Fandom

Not transformational or affirmational fandom, but a secret, third thing.

A while back, a fellow fandom writer tweeted about how music fans are missing out on the joy of absorbing songs into their own lives, applying them to their own experiences by instead focusing on the what and who the songs are about, and how they map onto the existing narrative of the performer’s life.

Essentially, the songs aren’t a piece of art for the audience to enjoy and relate to, but a puzzle piece to better understand the life serial they are following.

I agreed then, and I still do, but I’ve also come to see this investigative approach as a widespread fandom phenomenon that is encouraged by multiple corners, and seems to make up the bulk of today’s active, engaged fans. This mode of engagement is called forensic fandom.

Jason Mittell coined the term forensic fandom in the mid-aughts to describe contemporary television fandom as shaped by shows like Lost, The Sopranos, The Wire, which exemplify a new approach by the industry that, “encourages viewers to dig deeper, probing beneath the surface to understand the complexity of a story and its telling.”

Mittell was talking about television and media fandom, specifically, but it’s undeniable that this approach of investigation, interpretation, search for knowledge and ‘truth’ has spread beyond media and into the general fandom waters.

This ties into a lot of what I’ve been talking about since starting this newsletter. Over the past twenty years, fandom has grown exponentially, and over the past decade, it has fully gone mainstream. Yet, a lot of what would be considered traditional fandom practices such as fan fiction appear to be in sharp decline. I have blamed this on attempts by corporate forces to supplant fan creativity because the existence of creative works by fans is seen as money left on the table, but that’s an over-simplification. Fans are still out there, that much is obvious, they are simply engaging with their fan objects differently.

I haven’t had a name for this engagement until I came across Mittell’s term, but it feels entirely appropriate for the way fans have taken on the mantel of amateur detectives uncovering The Truth, putting things together, theorizing about signs and underlying messaging.

Part of this is a result of technology, even Henry Jenkins observed this in the 90s among Twin Peaks fans, who, “saw the technologies of the VCR and Usenet boards as essential tools with which to crack the narrative codes of the series.” Jenkins argued that our digital climate gave rise to so-called spreadable media that was intended to go viral, to go far and wide and broad. But this technology also allows—and encourages—those who pay close attention to notice discrepancies and connections, establish timelines, and build narratives.

Mittell suggested the media that encouraged forensic engagement was, instead, drillable. It would attract fewer total viewers and fans, but would take up more of their time and energy as their investment was encouraged. Sounds a bit like the superfan model, doesn’t it? The fandom pyramid where cult fans make up the smallest amount of any given fan-base, but spend the most time and money on their fan object?

The joke in One Direction fandom was always that they were essentially FBI/CSI level investigators based on the things that they uncovered. I discussed some of this in my stalker fans post; how fans somehow gained access to security footage of the boys in airports and hotels, how commonplace hacking and flight tracking was, and how anyone who came into contact with the band became fair game for cyberstalking.

I’m not going to claim that 1D fandom was the first outside of television to go forensic, but the proliferation of so-called “FBI fans” is undeniably tied to the rise of Twitter and Tumblr, which enabled fans to hone their investigative skills and demand more than what was willingly shared. And 1D essentially owe their career to Twitter and Tumblr.

Tumblr user sashayed said it well, and accurately described fans’ hunger for more knowledge as “rapacious,”

“One Direction is perhaps the first band to exist entirely within the Panopticon, from the very beginning, and yet even that was not enough for us. Can you imagine how difficult it would become to hold onto a ‘self’ when what people want most from you are the moments of your life that specifically are NOT FOR THEM? It wasn’t just what they DID, we wanted to know what they FELT, constantly. We demanded to know but we did not want to be TOLD. The knowledge could only be ‘authentic’ if it was not meant for us […] What we wanted was their interiority, and when we could not have that we invented it.”

As tongue-in-cheek as the post is, it strikes me as incredibly accurate. In my current deep dive of 1D fandom I came across a quote from a Big Name Fan who peaced out because there was “no puzzle to tinker with” as opposed to when the band was active and “the puzzle was still interesting and there were new pieces every day.” This isn’t an outrageous claim if you were around for the hey-day. It’s what sucked me into my cultic experience, after all.

Part of the ballooning of this approach is undoubtedly because the media is engaging in it as well. It may have started with fan magazines and tabloids which ran blind items that relied on readers putting pieces together, but it has spread to mainstream publications doing their own investigations and reporting on fan theories that should remain underground. Remember the Kate Middleton photoshop scandal? Or the New York Times publishing what can only be considered a Gaylor manifesto? Or aVanity Fair writer talking about being “deeply committed” to the veracity of a romantic relationship between Harry Styles and Louis Tomlinson?

This reporting and engaging in fannish hypotheses isn’t seen as clickbait or engagement farming for true believers: they are seen as proof and validation.1

Where I disagree with Mittel is his claim that forensic fandom entails more engagement with the core text rather than paratexts. Maybe it’s because paratexts have proliferated in today’s climate, but I think it’s the opposite.

Paratexts are more widely distributed and accessed than source material, and they are where the dots are connected, where hypotheses are presented and theories debunked. Paratexts are algorithmically pushed our way on the platforms we inhabit based on our interests, and many of us will know more about the discourse around a particular piece of media or celebrity than have actually engaged with it directly.

The omnipresence of paratexts is also related to the way the fan objects themselves are sustained: by evangelists and proselytizers. Mittell says that this is how forensic fandom is spread, “via proselytizing by die-hard fans eager to hook friends into their shared narrative obsessions,” and the way this is done is via paratexts.

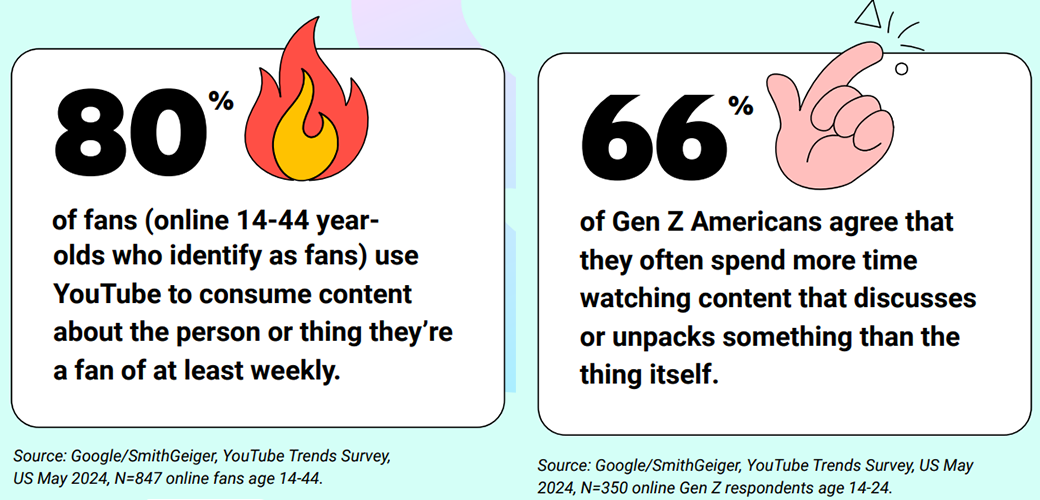

YouTube’s 2024 Fandom Trend Report tells us that 66% of Gen-Z users engage more with paratexts than the source text, and 80% of self-identified fans seek out paratexts on a weekly basis.

Another notable statistic from the YouTube report is that 8% of self-identified fans consider themselves “professional fans.” This means they earn money through their fannish endeavours, i.e., through creating more paratexts. These professional fans can also be seen as the part of the proselytizing class that is intent on spreading the good word, or the Correct Interpretation on any given fan object.

Forensic fandom may not be the easiest to participate in, but it is easy to consume, it’s easy to dip your toe in the stream of conspiracies and spread the word. It’s also easy to get invested through this type of content, which ties us back into the superfan economy that depends on the combination of attention and affect. And what better way to fuel both than with revelatory deep dives that uncover The Truth?

I can’t help but feel like this is partly why fandom feels so fraught these days. It leaves us with fan wars and stans battling for narrative dominance. Because we’re not dealing with appreciation so much as interpretation.

And sometimes, fans are correct. But their investigations don’t exist in a vacuum and again, when we’re dealing with real people, this becomes problematic and an ethical challenge. This may be a post for another time.

Love this. The Gaylor fans come to mind.

'Drillable' is an interesting way of putting it, because with this kind of 'investigative analysis' you can keep drilling down without ever reaching the 'core' — instead you just keep going through an endless surface layer of paratext, fanlore, cosmetic trivia, &c. (If it were still the blessed '90s I'd start talking about fractals now.)