No, fandom was not invented by slash fans.

The current dominance of slash/queer content makes it easy to reframe the past: let's not.

My problem with the claim that “fandom was invented by people who wanted to see kirk and spock fuck” aka slash fans, is twofold:

it erases the reality of slash fandom’s marginalization

it frames fandom as inherently progressive and/or tolerant

Fandom and fandom management predates Star Trek. It even predates television.

Many people today seem to think fandom is an internet phenomenon, which underestimates the human need for connection and creativity.

Because of the concept of survivorship bias it’s nearly impossible to be certain of when exactly fandom started or which fanzine or convention was First. I wouldn’t be surprised if there were undiscovered fan communities of yore to this day. But it’s certain that fandom most definitely predates Star Trek—even fan management and publicity stunts predate the advent of television.

The Hollywood star system, as it is known, had the effect of their talent amassing fan bases and as a result, fan mail started to arrive in droves. Fan mail, which had never been dealt with on such a scale, now needed entire departments of staff to sort through. These letters provided essential feedback to the studios, they needn’t take casting risks; they knew exactly who the public wanted to see more and less of.

On the non-profit fronts, fans created fan clubs and fanzines for each other, and sought each other out before the ease of broadband. The human need for connection based on affinities is, well, human, and wasn’t invented by the World Wide Web, only facilitated by it. An oft-cited first fanzine was The Comet from 1930, and when it came to early zines and fan clubs, adult/sexual content was not the majority.

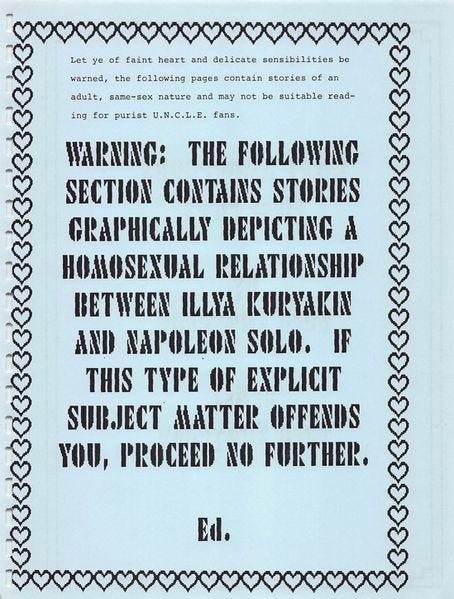

Why would advisory warnings exist for slash if slash was the root of fandom?

As recently as my bandom days, the late oughts, slash “warnings” were still a thing and were still requested by readers.

The persistence and growth of these slash fandoms despite the threat of legal action, in-group marginalization, and insults from official figureheads is worth remembering and noting.

To claim that Kirk/Spock shippers invented fandom is to erase those challenges and diminish the decades of clashes with mainstream fandom— something that happened to slash fans in all fandoms.

It is true that Star Trek fandom was an early adopter of wanting representation and asking for it; it’s no surprise that the show’s universe was seen as a possible vehicle for sexual diversity, as the show made headlines in the 60s for portraying the first televised interracial kiss. They boasted about their contribution to the civil liberties fight, and as a representation of a possible harmonious future.

In 1986, the Gaylaxians, a Boston-based science-fiction fan club, asked Gene Roddenberry himself if the utopian world depicted would be accepting of gay relationships, as the story was set in the 24th century, wouldn’t the stigma between same-sex relationships have eroded by then? At the time, Roddenberry agreed, even suggesting that some of the characters might be gay.

This allowed fans to lean into the suggestive, performing resistant readings of the show as they awaited long-promised representation. At one time, Roddenberry commented that it would be difficult to portray homosexuality on the show because their futuristic universe was past the issue. Besides, in the future sexuality, “will not be labeled.” How can you portray something that has no label?

The representation that these fans wanted never became canon or official, which kept slash fans on the sidelines.

Fandom isn’t inherently progressive

To suggest that fandom was created by slash fans is to label fandom as inherently progressive, rather than communities of regular people brought together by shared affinities. When it comes to culture, we cannot exclude our tastes from the tastes of people we hate. Or as Leslie Fiedler put it, “in the enjoyment of popular literature one is joined to those people who are felt to be socially reprehensible, wicked, whatever your social code and values may be.”

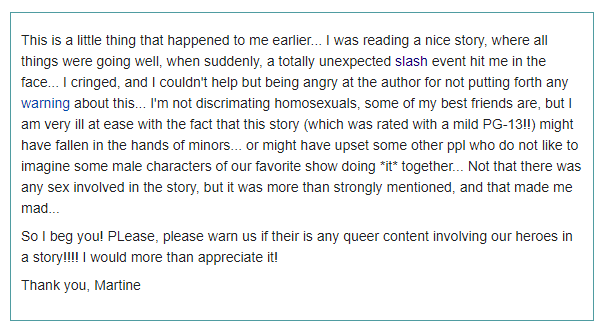

Because we’re talking about slash specifically, it’s the existence of homophobia and perpetuation/enforcement of rigid gender stereotyping that sticks out the most. Just because people were reading and writing slash, didn’t make them progressive or inherently accepting.

I’ve dug deep into the fandom history of ratings and trigger warnings, and it may be surprising to know how often the request for slash warnings came up and how they came up, how it was phrased, even when dealing with non-explicit content.

An example of offence taken at a non-explicit slash story below—

I personally didn’t encounter many of those complaints as I came around later, post Queer As Folk and mainstream gay pairings, but as I said, I still saw the actual slash warnings in use.

Another thing that stood out was the trope of, “We're not gay; we're just in love,” that manages to stigmatize same-sex attraction while using it as entertainment. This was widely discussed in Livejournal’s Fanthropology community.

I have read plenty of slash stories where the author makes a really big point of having the male characters constantly affirm that they are "NOT gay" they're just into blankety-blank other male character. This seems to me, to show a level of squeamishness/discomfort both with an actual "gay" identity and a need to affirm the "masculinity" of the characters. Which ties in with the previous mention of the subtle and not so subtle misogyny in the slash world.

— comment on the “not gay” trope, Fanthropology, 2005

There seems to be less of this trope today, however, what has become unavoidable is the insistence that “top and bottom” preferences are actually identities set in stone, and they can be detected by outsiders. There is no universe in which I consider it progressive that communities have formed around the deeply held belief of what strangers’ and fictional characters’ sexual preferences are.

We’ve gone from groups of people clinging to particular sexualities for their faves to clinging to particular sexual roles/preferences/kinks.

The willingness to believe that slash was the start of fandom is likely related to the present-day glut and over-the-top industry sanctioned fan-service. But that just means it sells—nothing more, nothing less. It isn’t so much about mass appeal or breadth of appeal as it is about depth of appeal, if that makes sense. That’s how stan culture works, after all.

It’s better for business to let the public fight it out and play coy, letting them believe what they want to believe. A notable recent example would be that of Supernatural’s Misha Collins— he “accidentally” came out as bisexual and got on Twitter to walk back his statement.

In years past it would be easy to assume that his retraction might’ve been encouraged by the businesses behind the product he was representing. But apparently, the reverse is what happened.

At a Convention in April, he recounted the experience recalled receiving a call from Warner Bros. after his original comment had made headlines, asking him to, “let it lie.” Apparently, they told him it, “would be better for the show.”

Whether it’s true that it would have been better if the fandom was allowed to believe indefinitely, the reality is that someone in charge thought it was. This is a massive shift from years ago, but as I noted in my mainstreaming of real-person slash post, it’s been building for a while. The taboo of slash content has been usurped from above with the realization that it might be good for business.

It’s not fun to think about being catered to for ROI rather than witnessing something authentic. It isn’t comfortable to think about or discuss, particularly if fandom has been nothing but welcoming in your experience, or if it’s been a gateway to self-acceptance and self-discovery.

But the days of private fandom are long gone. I consider it important to remember our role as an audience compared to fan objects and the industry that feeds us content. We are not immune to influence, whether from official sources or from our peers. We are still in public, and that makes us more vulnerable to influence and meddling from many different corners. We are not shielded or immune, and it’s worth reminding ourselves of that.

I was in fandom spaces between 1995- 2002 or so. It's wild because slash/yaoi was considered edgy and you had to know how to find it. Heck, being in fandom was an "outsider" activity. There was a wall between fandom and real life and I've seen how the wall has crumbled. I wrote fanfic but I was a teenage girl. I have acquaintances almost 40 years old just like me that are still very teen girl fannish, I'm talking Inuyasha posters in the living room at age 38, so it's not just Gen Z being quirky. I have my moments because you can't banish fun just to be an adult, but I'm a great believer that there should be a wall between fannish pursuits and your real life.

I was involved in both yaoi and mainstream anime fandom in the late 90s and early 2000s and it wasn’t unusual for the women writing (and buying) yaoi to talk about how homosexuality was a sin but this was all fiction so that made it okay. The shift to slash becoming dominant—and adjusting to become “queer” instead of yaoi and slash—was noticeable! It altered the landscape so much