Women and the commodification of gay sexuality

The market for sexualized images of gay men--outside the gay male demographic--is expanding, but to whose benefit?

The last time I wrote about slash, it was about the mainstreaming of the fandom concept itself and how the industry leaned into it with their targeted advertising and fandom management. But that was about internal fandom politics, not the offline culture shifts, the selling of gay sexuality to women.

It’s re-listening to old episodes of the once syndicated call-in radio show Loveline that has brought on this exploration, because they made the claim—repeatedly—that women are actually disgusted by the thought of explicit gay sex.

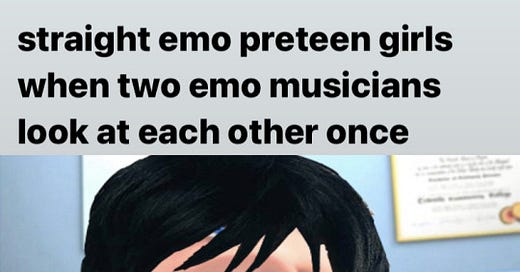

It was a strange claim to make even back then, in the 1999-2004 years, because it’s exactly when slash fans started making noise, thanks to the rise of emo culture. In fact, when Linkin Park guested on the show in 2003 they received a call asking about fan fiction. There was no elaboration as to what pairings the fanfiction explored, but considering the archives of LP fiction, much of it was intraband same-sex romance.

There were audiences for that content from long before then, slash communities that thrived for decades offline and out of the spotlight. Slash isn’t even the only version of gay romance out there, guy-on-guy, boylove, yaoi, MLM and so on, available for those who went looking.

Still, the millennium shift marks a distinct move towards the commercialization of gay content; it became worth investing in the niche audience it appealed to. In the Americas, it came on the heels of the success of Russell T. Davies’ 1999 show Queer As Folk, a British no-holds-barred look at the Manchester gay community. While it was expected to draw in gay audiences, the amount of women watching and getting invested was a surprise to the shareholders, and wasn’t something to ignore.

A year later, the eight-episode half-hour comedy show was remade in the US, keeping the title but expanding it into a one hour 22 episode show. There was a lot of skepticism about how watered down the remake would be, but producers Ron Cowen and Daniel Lipman were determined to keep it as explicit as possible.

“There's an audience out there that's underserved, and there's also a surprising crossover audience with women, which I don't think people realize.” - Ron Cowen

The budget for the promotional campaign was reportedly over 10 million, with a heavy focus on local gay communities but also mainstream audiences. Local VIP “coming out” parties, a special 1-800-COMINGOUT number to drive subscriptions to the broadcasting channel, swag, merchandise, direct-mail and public advertising targeting gay communities.1 It was one of the biggest campaigns blasting out gay content to mainstream, and it was a massive success, bringing in more than the expected gay audience.

Cowen told the SF Chronicle in 2003, “[the purpose] is to piss people off and to annoy people.” By then the show was already a massive success, and the suggested provocation could be attributed to Showtime’s mantra of No Limits. The lesbian counterpart, The L Word, would hit the air but a year later. Showtime had found their niche, and they leaned into it.

This was also around the time that the Canadian affiliate, Showcase, launched their promotional campaign known as, “Thanks Showcase.” A wide-reaching campaign with print, out-of-home and television spots, all working in concert to suggest Showcase is the place to go for naughty non-normative/unexpected content.

As Wendy Peters noted in Pink Dollars,2 the ads were selling a green light to transgress, in a sense selling queerness itself. It was an attempt to spice up the life of the average Joe, who would have remained ignorant of all he was missing out on if it weren't for Showcase. While this can be seen as a win for representation, Peters pointed out that this isn't happening without a cost,

“While entering popular culture is undeniably an important political objective for a marginalized group in terms of visibility, it also marks a moment of commodification: identities have the potential to create profits for large media conglomerates.”

Unsurprisingly, both QAF and TLW were greenlit for reboots, another nostalgia grab with a niche audience. While The L Word: Generation Q is currently on its third season, QAF (2022) only lasted one season, and did not inspire the same fandom as the original. The Datalounge crowd blame the lack of focus on female audiences, leaning into the niche too much.

This, along with Billy Eichner’s recent gay rom-com Bros not living up to the expected audience turnout suggests there is a disconnect between what is being represented and what sells. Bros could’ve done well had it been marketed differently, but that might have gone against the entire point of making the film in the first place; not to appeal to women, but to tell a gay love story.

Still— the focus on heterosexual women is too narrow. While Bobby Noble claims that, “heterosexual women constitute a powerful emerging demographic as consumers of sexualized images of men -- even, or perhaps especially, queer men--in popular culture,"3 his own work discusses how the female audience has large lesbian, queer and trans spectators. What seems to be the most relevant is really that there is a market for sexualized images of gay men outside the gay male demographic.

Lucy Neville’s book, “Girls who like Boys who like Boys,” is a cohesive exploration of the phenomenon, taking a much broader look at the audiences and relations with “m/m sexually explicit media.” It is suggested that the majority of women engaging in slash content in fandom identify as bi- or pansexual, followed by heterosexual, asexual and homosexual, in that order.

This isn’t an attempt to further alienate straight women as the concept of “queer heterosexuals” is explored in detail. That women might be drawn to queer content because it is queer opens the door to an expanded category of “queer.” Sex educator Tristan Taormino is quoted as welcoming those women, adding, “being queer to me has always been about my community, my culture, and my way of looking at the world, not just who I love and who I fuck.”

In fact, while most industry insiders discuss what “straight women” love, the label itself is not that frequent among spectator and fandom communities. There is even suggestion that, “straight women might be the ultimate Queer quotient,” something Romy Shiller explored in a 2003 piece on QAF’s appeal to women.4

This expansion of the queer umbrella predates my own encounters with it, the academic discourse not part of my fandom experience back then, but archives reveal many past discussions in fandom about it representing “queer female spaces.” It seems in these situations that it’s not necessarily about same sex attraction but about “norm violations,” at least in these contexts.

It shouldn’t be a surprise that it isn’t just self-identified straight women who consume slash and gay content; porn surveys have shown that lesbians are a large audience for gay porn. Much of the fandom discussion revolves around the lack of female characters being represented on screen—which is a very real numbers problem if you’re interested in exploring character interactions and romances. Lesbian viewers and fans of QAF were known to dislike the lesbian representation on the show, instead leaning towards the more dynamic gay characters and relationships.

There is also the eternal question of why— why are women drawn to content where they aren’t even present? There are multiple theories, most not too concerned with what the women themselves think. It’s blamed on internalized misogyny and fetishization, but fails to look at the history of the content itself or the history of the communities that formed around it.

Tumblr user toastystats has done multiple shipping deep dives, looking at the divisions between male and female representation, “I found that shows with more major female characters lead to more femslash (also more het).” Toastystats also conducted a survey of fanworks inspired by the Tumblr group-creation Goncharov. The fictional crowd-sourced universe has resulted in more femslash than slash, suggesting there may be something lacking in female characters presented on screen, or a difficulty relating to them and their potential romantic relationships.

A theory I find interesting is that of, “eroticizing equality,” the concept that versatile gay men represent an equal relationship with no inherent expectations. There are no existing scripts and expectations boxing you in, no presumption of passivity or submission, but rather a landscape where the roles and relationship can be worked out to the benefit of all involved.

This isn’t to suggest that fandom and slash audiences are somehow better; rejecting some stereotypes, some gendered expectations and some norms doesn’t absolve the audience from building boxes of their own and demanding adherence to their established preferences. This is where things like the “D/S universe” and “Alpha/Beta/Omega” universes fit in, re-creating old norms with new guidelines. But that’s a topic for another day.

THE MEDIA BUSINESS: ADVERTISING; The Showtime Network prepares a $10 million campaign blitz for its 'Queer as Folk' series, NYT, 2000, Stuart Elliott

“Queer as Box: Boi Spectators and Boy Culture on Showtime's Queer As Folk,” Third wave feminism and television: Jane puts it in a box, 2007, Bobby Noble

QUEER AS FOLK, FAB Magazine, Number 213, April 23, 2003, Romy Shiller

Great post! As a gay man, I find for-woman-by-woman "gay" romances such as Heartstopper and Red, White and Royal Blue rather alienating (although I have to admit that there are plenty of gay men who lap up these fantasies). Perhaps gay men should feel flattered that women find our relative ease with sexual and gender fluidity so aspirational? It also seems to me that the audience for drag is skewing more and more female.

"A theory I find interesting is that of, “eroticizing equality,” the concept that versatile gay men represent an equal relationship with no inherent expectations."

Hadn't considered this before; the idea of not necessarily looking at the gay male relationship as erotic, but being envious of or living vicariously through people who have the fearlessness, authenticity, etc, that they want.